Bringing Cities to Life: The complex relationship between green space and mental wellbeing

This week’s guest blog is from Victoria Houlden, a Post-Doctoral Research Assistant with the Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies at Newcastle University. Victoria outlines her research on the relationship between urban green space and a resident’s mental wellbeing.

Over half the world’s population today – and 80% in the UK – resides in urban areas, creating a challenge for urban planners to efficiently accommodate increasing numbers of residents in a healthy and positive environment. Mental health in particular is important, with statistics showing that one in four of us experience mental health difficulties each year, while those with better, positive mental wellbeing display increased levels of longevity, productivity, and prosperity. In fact, the UK government now measures mental wellbeing, alongside the traditional GDP, as an indicator of national progress.

Green space in the urban context

There is a lot of evidence for the general health benefits of exposure to nature. But the specific relationship between urban green space and mental wellbeing is much more complex and the evidence varies widely.

To further complicate matters, at the same time, the concept of mental wellbeing is often simplified or misunderstood. Mental wellbeing is a measure of positive mental health, distinct from mental illness, and comprises two domains:

- hedonic dimension, which includes the pursuit of pleasure, satisfaction and pain avoidance

- eudaimonic dimension, which focuses on self-realisation, purpose in life and psychological function.

The current evidence base

We recently undertook a systematic review of literature to aggregate the evidence for an association between green space characteristics and mental wellbeing, revealing a surprising lack of research on urban green space and multidimensional mental wellbeing. Green space was measured in different ways according to the study design, which we aggregated into six broad categories:

- local provision of green space

- types of green space

- accessibility

- views of green space

- visits to green space

- subjective connection to nature

We were only able to detect adequate evidence for the association between local-area green space and life satisfaction, an indicator of hedonic wellbeing, but not personal flourishing. Associations between all other green space concepts and mental wellbeing were either limited or inadequate.

This means, despite a growing interest in designing green space for health, the evidence is not currently consistent or specific enough to guide urban planning decisions.

The benefits of being near, and accessing, nature

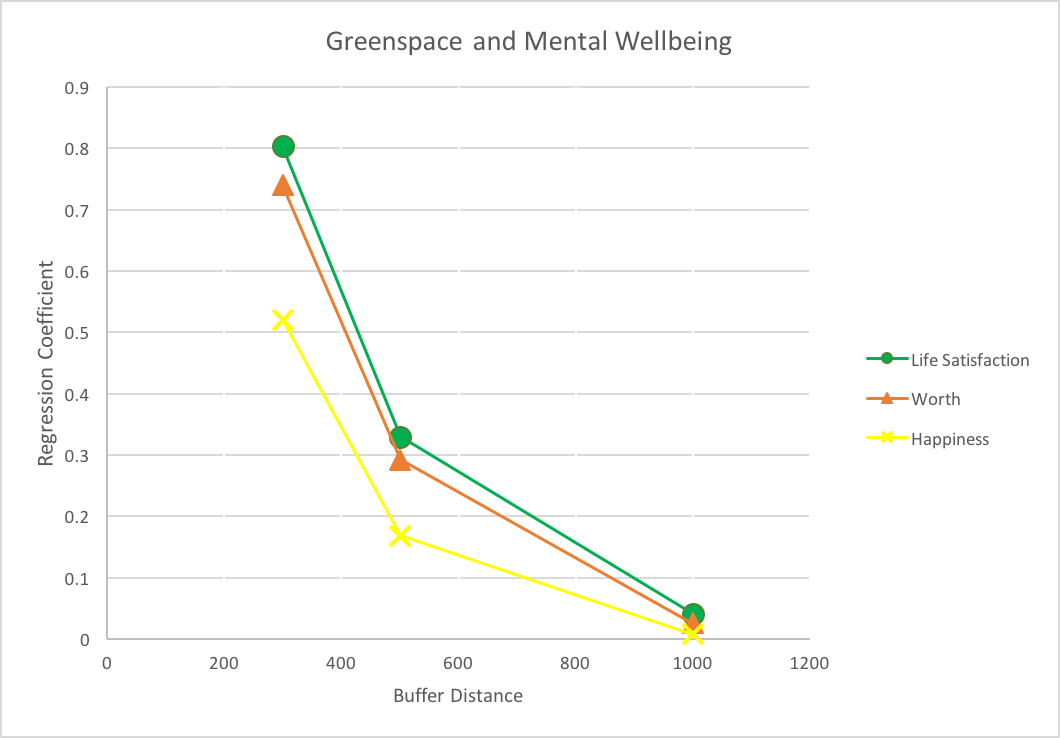

In my own study of over 20,000 residents in London the amount of green space available within 300m of residents homes was strongly and significantly associated with hedonic wellbeing (measured via indicators of life satisfaction and happiness) and eudaimonic wellbeing (sense of worth).

Associations appear to be strongest for those having access to greater amounts of natural green space (which includes, for example, nature reserves and woodland), rather than more formal parks and gardens or outdoor sports facilities.

This leads us to believe that it is not only green space nearby which may be important for our mental wellbeing, but that having access to natural spaces may feed this evolutionary desire to connect with nature. They may also provide a welcome escape from the hectic, often overwhelming stimulus of modern cities.

What does this mean for urban planning?

With urban growth currently increasing at an unprecedented rate, there is rising pressure on city planners to ensure that limited space is put to its optimum use. Green spaces are only present in urban areas at the expense of buildings, and as such it is important that they are designed well to offer a greater benefit to the widest population, by including accessible natural areas close to residents homes.

People are at the heart of planning. We design and create environments for human activities: living, working and socialising; by designing with an informed focus on health and wellbeing, we may be able to optimise both human lives and the effectiveness of the city.