This week’s guest blog is from Larissa Pople, Senior Researcher at The Children’s Society, on their latest Good Childhood Report, published this week. It is their annual digest of the latest trends, statistics and findings relating to children’s self-reported wellbeing in the UK. Here she pulls out some key findings on the differences in the wellbeing and mental health of boy and girls identified in the report.

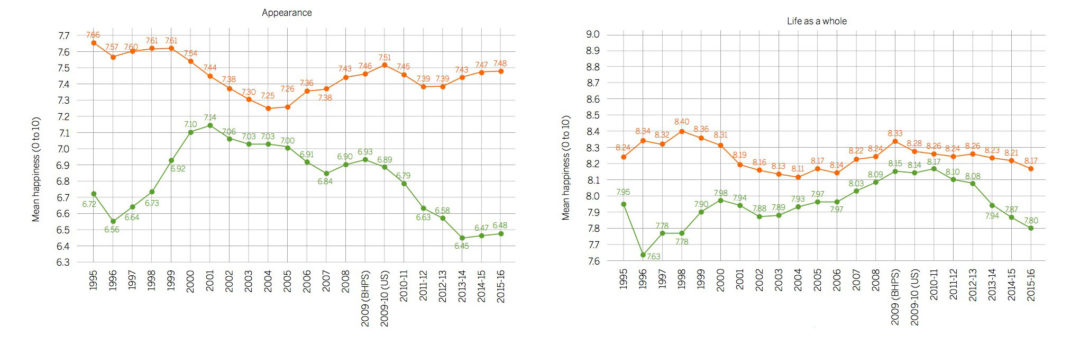

Each year, we present time trends in children’s subjective wellbeing, updated to include the latest available data. This year, we were able to look at time series data back to 1995 thanks to the recent harmonisation of Understanding Society with its predecessor the British Household Panel. This reveals different patterns for different aspects of children’s lives, and over different timeframes. Children’s happiness with family, schoolwork and school increased over the period from 1995 to 2016 – however, for happiness with friends and life as a whole, an increase between 1995 and 2009 was followed by a subsequent decrease between 2009 and 2016.

Divergent trends are not necessarily surprising. Given the multitude of factors that we know to be important for children’s wellbeing, the trends that we see for different aspects of wellbeing are unlikely to be attributable to a single policy or cultural phenomenon.

Difference between boys and girls

The longer time series gives an intriguing perspective on gender differences:

- Girls are less happy than boys, both in terms of their life as a whole and their appearance.

- The difference is of a similar magnitude to that evident 20 years ago.

- In this light, children’s usage of social media and the digital world seems less likely to be the only or main explanation for gender differences in wellbeing.

Source: British Household Panel Survey, 1995 to 2009, children aged 11 to 15, weighted data. Understanding Society, 2009-10 to 2015-16, children aged 11 to 15, weighted data. Three-year smoothed moving average from 1997 onwards.

Mental health measures

In this year’s report, we also draw on data from the Millennium Cohort Study. We now have data on the children included in this study up to age 14, where we can begin to explore different measures of wellbeing and mental health alongside measures of truancy, physical activity and self-harm.

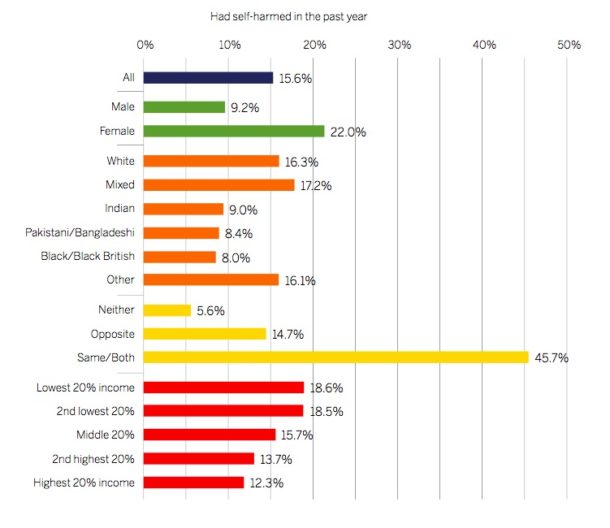

Our analysis reveals deeply worrying self-harm figures for this age group:

- One in five girls had self-harmed in the previous year.

- Almost half 14 year olds who were attracted to the same or both genders had self harmed.

Source: Millennium Cohort Study, Wave 6, 2015 (when children were aged 14)

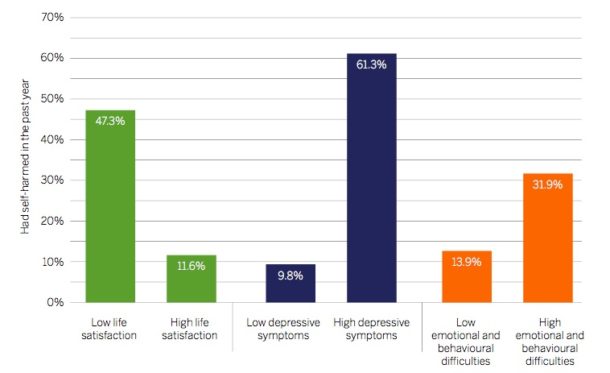

Analysing a range of wellbeing measures gives us important information about the different challenges facing different children. Our analysis found that the three different measures of wellbeing and mental ill-health included in the Millennium Cohort Study identified different children as in need of support. For example,

- Boys – and children in low-income households – were more likely to be identified by a measure of emotional and behavioural difficulties (the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire),

- Girls – and children who said they were attracted to the same or both genders – were more likely to be identified by measures of subjective wellbeing (happiness with life as a whole) and depression (the Moods and Feelings Questionnaire).

The strongest predictors of self-harm were the depression measure (the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire) and subjective wellbeing, more so than the 20-item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. This may be due to the fact that the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire was reported by parents while the other two measures were reported by children. However, this in itself is an important conclusion to draw and adds weight to our long-held belief that data from children must be considered the gold standard.

Source: Millennium Cohort Study, Wave 6, 2015 (when children were aged 14)

Larissa leads The Children’s Society’s wellbeing research programme, which has generated a series of annual Good Childhood Reports and local area studies of wellbeing.