Can wellbeing evidence inform students’ study and career choices?

Last week, the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) released the results from the new HE Graduate Outcome Survey. The data shows what students were doing 15 months after the 2017 to 2018 academic year.

In addition to job type and salary level, the survey includes the four ONS measures of life satisfaction, worthwhile, happiness and anxiety. These measures are important because they tell us whether graduates are leading happy and fulfilled lives, over and above their average salary.

Importantly, it is the same data used nationally by the ONS and internationally by the OECD to track people’s wellbeing. This better consistency and comparability of measurement helps us work out what works.

Which course graduates go on to have better wellbeing outcomes?

In Figure 1 below we can see the proportion of graduates in each subject who report very high subjective wellbeing. This suggests the subject students choose impacts the levels of life satisfaction, happiness, feelings of worth and anxiety.

- Graduates who study education and subjects connected to medicine appear to do very well in all four dimensions of subjective wellbeing. They score similarly to the UK general population (as recorded by the ONS in 2018/19).

- Languages, creative arts and mass communications graduates consistently report lower levels of subjective wellbeing than their peers and the UK general population.

- Other subjects show a mixed success story. For example, medicine and dentistry students are likely to be very satisfied with their life, and feeling what they do is highly worthwhile. Yet they score significantly worse than the UK average in terms of happiness and anxiety. Those in veterinary science also present mixed outcomes: they rank lowest in happiness and anxiety, but they rank fourth – and much higher than the graduate average – on feelings that what they do is worthwhile.

Prospective pay impacts current student wellbeing

Things become more nuanced when we take into account payment levels associated with each course of study.

In the majority of subjects, the proportion of graduates with high (7-10) life satisfaction, happiness or purpose increases along the proportion of graduates with high (above £24,000) salary.

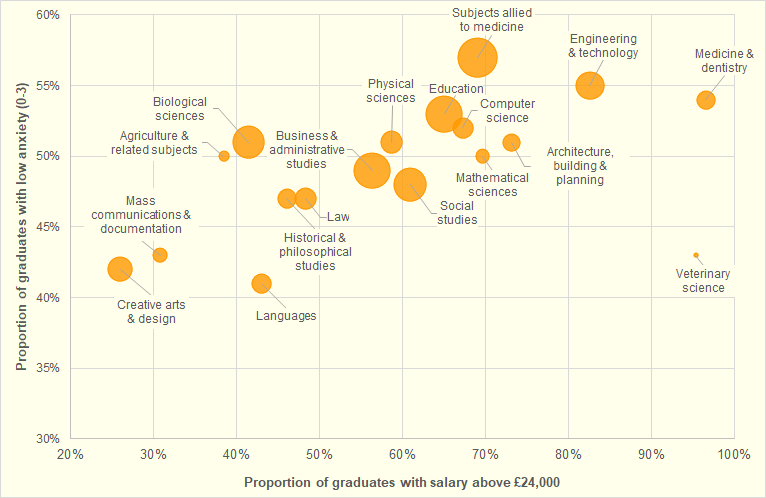

The correlation is particularly strong with life satisfaction. And yet, there are some exceptions. As we can see in Figure 2, low anxiety and high wages are still decently correlated. But we can find courses like veterinary science, where as many as 95% of graduates earn over £24,000, and only 43% report low anxiety (compared to 63% in the UK).

Meanwhile, graduates from biological sciences are less likely than other graduates to suffer from stress (51% reported low anxiety). But the probability of earning a high salary is just above 40%.

Figure 1: Subjects of study rank ordered by subjective wellbeing

Figure 2. Anxiety and salary by subject area

How can prospective students and their families use this information?

If appropriately used, this graduate wellbeing data can help young applicants to make a major life decision: choosing a university and subject of study. It will help them to base their decisions on robust evidence about subjective wellbeing by occupation, and not solely on expected economic rewards that can be often at whim of external labour market forces. As Neha Agarwal, Head of Research and Insight at HESA said earlier: “one could certainly develop a more thorough definition of ‘graduate success’ by incorporating graduates’ personal wellbeing.”

As they make their university choices, young applicants dive into a sea of information and juggle different criteria to guide their decisions (as if family opinions were not enough!). Online sites such as Discover Uni, and other ranking tables in addition to Universities’ own websites offer a good starting point. Applicants can find information about how median earnings after 5 years vary by course and university chosen, how universities rank in league tables, types of learning and assessment styles etc. Tera Allas, Director of Research and Economics at McKinsey & Company, illustrates through a personal case study how young people can make use of this varied information to better choose university subjects or career paths. Subjective wellbeing levels by occupation are now a crucial piece of information to put into the equation.

Looking beyond salary prospects

The literature on work and wellbeing supports this ‘look-beyond-salary’ paradigm shift. The evidence shows that the wellbeing benefits we obtain by participating in the labour market are driven by many other factors apart from (and not in replacement of) wages.

Employment also offers job security, a sense of agency and autonomy, interpersonal contact, opportunities for skills use, time structure, physical security, a valued social position, and a sense of purpose*. Jobs that offer such a range of capabilities and conditions to fulfill our material and psychological needs are what we call good quality jobs.

In practice, the different dimensions of job quality can be highly connected and it is often the case that the more an occupation pays, the better its overall job quality. Similar to what we observe in many subjects of study, both income and subjective wellbeing are strongly and directly correlated in certain occupations (see Figure 3).

Blue collar, white collar, and wellbeing

Generally, people in ‘blue collar’ and more labour intensive occupations are at the lowest income level and evaluate their lives around 4.5 out of 10 on average. People in ‘white-collar’ and professional occupations are at the highest income levels and evaluate the quality of their lives at over 6 out of 10. There is also evidence that some areas of the UK do better than others when it comes to job quality.

According to the 2017 World Happiness Report, the occupational gradient is also directly correlated with positive and negative affect experiences (such as smiling, laughing, enjoyment, or feeling well rested), even when controlling for salary levels.

Figure 3. Life satisfaction and salary, by profession (ONS, 2016)

What to consider before picking a course

Since the type of occupation is commonly correlated with job quality, they are often used interchangeably. However, there are some nuances worth considering before assuming that the occupation you choose will determine the quality of your job and your overall wellbeing.

Which professions buck the wellbeing trend?

These are only averages and there are many occupations that depart from this trend. For example, beauticians, clergy, hairdressers, pub landlords, and bakers are ‘some of the lowest-paid but have modest overall job quality’.

On the other hand, some jobs related to finance, law, IT, and various other licensed professions are some of the highest paid but have only modest overall job quality. This is why dashboard indicators of job quality are so useful!

Getting the right fit with personality, institution, and values

Our wellbeing outcomes will also depend on whether there is a good ‘fit’ between the job and an individual’s motivations, personality and skills. It is rare to find jobs that would be ideal for every kind of person, or as a colleague said “we can’t all be those happy clergymen”. Some subjects of study or higher education institutions might be better able than others to provide you with the right skills for your ideal job, but there will still be an element of personal values that will be entirely down to you.

All jobs can be good, fulfilling jobs

The evidence hardly supports the existence of inherently ‘bullshit’ occupations, despite the popularity that some anecdotal facts have gained around this issue. Rather than the occupation itself, at the end of the day it will be the working conditions, the opportunities for training, job design and organisation-wide approaches that will make us more or less satisfied with our work.

Experiences of meaningful work can probably be more easily obtained from occupations such as health and teaching professionals or personal care workers. However, in other types of jobs a sense of purpose, social value, engagement and ultimately satisfaction can be built up through job design and job quality improvement. For example, there is research** that shows that the probability of perceiving your job as socially useful is strongly correlated to:

- having supportive management and co-workers

- having opportunities for development or to apply your own ideas at work

- being able to work in teams

- being praised for doing a good work

- being able to influence decisions at work.

All in all, choosing which topic of study and occupation is right for us is quite a complex task. The important point is that students can make these decisions with confidence, and access to complete, clear, and interpretable evidence is key to achieving this.

The data released by HESA should not only help inform applicants but also guide higher education institutions. Many UK universities are under enormous strain at the moment due to the reduced number of students during and after the coronavirus crisis. This also seems an opportunity to revise their subject offer and keep open or place tuition fee incentives to fund those courses that are more likely to deliver better wellbeing outcomes for students and graduates.

The higher education sector is investing in a range of initiatives to improve student and graduate wellbeing and approaches that aim to measurably improve the life-long life-wide life quality of all 2.5 million UK HE students each year are to be applauded. After all, these are our leaders of the future, of our professions, our communities, of our country.