Self-report measures offer new insights into adolescent wellbeing

Our role as a What Works Centre is to synthesise and share high-quality, timely evidence that contributes to the global wellbeing knowledge base. This includes consolidating a legacy of learning from major projects such as Spirit of 2012 Carers Music Fund and National Lottery Fund £87m Aging Better Programme.

In today’s blog, we look at the latest learnings from HeadStart, a long-term programme measuring mental wellbeing among UK pupils aged 10 to 16. The programme is delivered by the Evidence Based Practice Unit at the Anna Freud Centre, and supported by the National Lottery Community Fund.

We consider the researchers’ use of mental wellbeing measure SWEMWBS, their key findings, and the learning implications for wellbeing research and policy.

Filling evidence gaps

Adolescence is a critical period for young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Understanding the predictors can help us better measure and target tailored and universal interventions.

A 2016 study by Dr Patalay and Prof Fitzsimons used adolescent subjective wellbeing and parent-reported mental health difficulties to determine that children’s wellbeing and mental illness are two distinct domains.

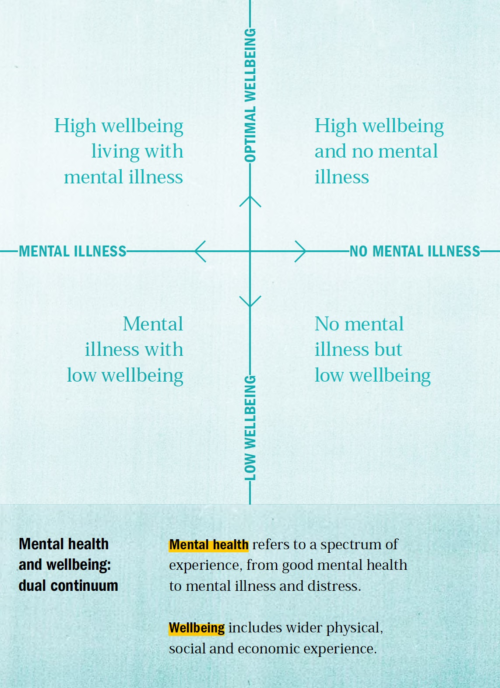

Figure 1 lays out a practical way to interpret and apply mental health and subjective wellbeing differences.

Figure 1. Step Change: mentally healthy universities, by John de Pury with Amy Dicks (May, 2020), Universities UK

HeadStart’s latest analysis extends the 2016 research by exclusively using young people’s self-reports across predictors.

Asking young people to assess their own mental health is important as they provide a unique, first-hand perspective. When asked appropriately, they are able to report their psychological distress and wellbeing.

This is important because there are more young people reporting mental distress than the number of young people in contact with mental health services.

Key findings

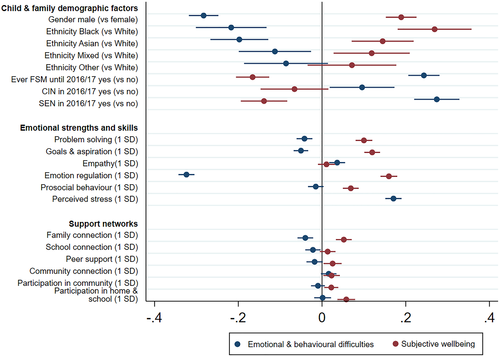

The study provides further evidence for differences in what predicts young people’s mental health difficulties and subjective wellbeing.

The study found:

- A moderate overlap between mental health difficulties and low subjective wellbeing at year 8, age 12-13.

- Predictors of both mental health difficulties and subjective wellbeing are:

- gender, free school meal eligibility, problem-solving, goals and aspirations, emotional regulation, perceived stress, and family connections and being Asian or Black (compared to being White).

- Predictors of mental health difficulties only:

- special education needs and empathy.

- Predictors of subjective wellbeing only:

- Prosocial behaviour – such as helping, cooperating and sharing – and peer support.

The findings provide further evidence that mental health difficulties and subjective wellbeing are related but distinct constructs with a number of distinct predictors.

Figure 2. Regression coefficients predicting mental illness and subjective wellbeing

What was done?

HeadStart’s longitudinal study surveyed 13,500 adolescents in year 7 (aged 11-12) and again in year 8 (aged 12-13). It investigated which socio-demographic factors, emotional skills, and support networks, measured in year 7, predicted adolescent mental health difficulties and subjective wellbeing measured in year 8.

Mental health difficulties were measured using the aggregated Emotional Symptoms and Conduct Problems subscales of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Higher scores indicate greater symptoms.

Subjective wellbeing was measured by the team using the seven-item child self-report Short Warwick and Edinburgh Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS). Higher scores indicate greater positive subjective wellbeing.

Scores on mental health difficulties and wellbeing were standardised to enable the values to be compared. Socio-demographic factors were gathered from the National Pupil Database.

What evidence should be built next

The research indicates there are key areas that should be further looked into:

- Problem-solving

The paper found that high problem-solving skills were associated with both low mental health difficulties and higher subjective wellbeing. It has been suggested that problem solving leads to quality relationships and an enhanced quality of life. It is also likely to improve feelings of agency and control.

As a coping mechanism, it can be helpful for long-term wellbeing because it may help remove the cause, in contrast to solely avoidant, socially-supported or emotion-focused strategies which may help reduce short-term stress. We need a greater understanding of how the intrapersonal and interpersonal process of problem solving helps us feel good and function well, and what can be done to improve this area.

- Empathy

In the study, high empathy was associated with higher mental health difficulties. Defined as the ability to understand and share the feelings of another, empathy has often been promoted as an emotional skill to develop. Whilst it’s possible that this just indicates female emotional distress, given this duality and potential vulnerability of those with strong empathy, it needs further exploration to ensure policy and interventions are designed with care and that they promote resilience.

- Gender differences

Across all models in the study, being male was associated with lower mental health difficulties and higher subjective wellbeing. We know from work pioneered by NPC that wellbeing declines as children get older, with this being steeper and starting earlier for girls. This needs further understanding. A question remains as to whether male distress is being picked up sufficiently in survey questions. Qualitative research is needed to understand whether male psychological distress is indeed lower, or whether the measures are not working to detect it for this population.

Interventions and policies must focus on building mental capital, as well as treating symptoms of mental illness, if we want children, and society, to flourish and lead meaningful, happy lives.

Further examples of evaluating the impact of investing in wellbeing research include the National Lottery Fund £40m Wellbeing 2 Programme, and Spirit of 2012 Trust’s first three years and Sporting Equality Fund.

These programmes have looked at specific groups of people and topics. And when comparable wellbeing metrics such as ONS4 or WEMWBS are used, we can bring these learnings into our broader thematic evidence reviews – like those on Social Capital and Loneliness – so that we can learn together.

Measure the difference you make and contribute to the global knowledge base.