All I have to do is dream? The role of aspirations in intergenerational mobility and wellbeing

New research suggests that unrealistically high aspirations in teens could have a negative impact on wellbeing in adulthood. Negative effects on subjective wellbeing also accrue if there is an aspiration gap between teenagers and their higher-aspiration parents.

There is already evidence that financial constraints, the education system, or genetic inheritance all affect social mobility. Our analysis suggests that less ambitious career goals may also be part of the explanation for limited social mobility. Specifically: there is a positive correlation between high aspirations and high achievement.

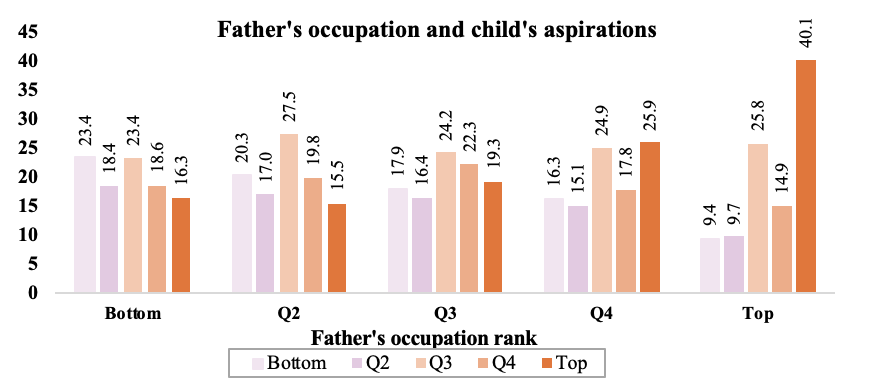

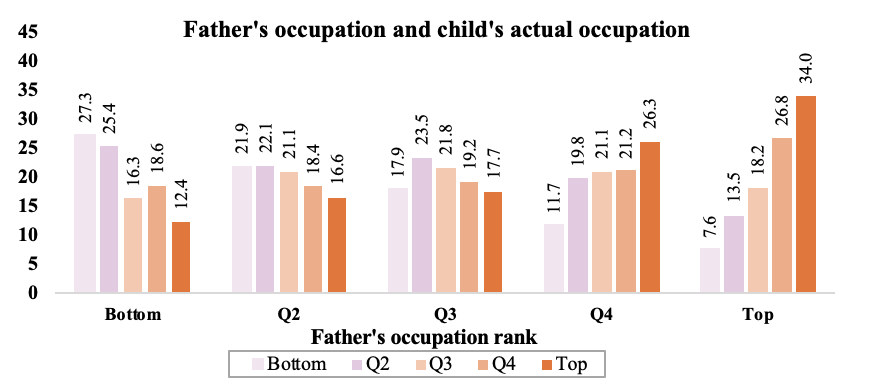

In our research, we find that educational and occupational inequalities already exist in young adults’ aspirations (see Figure 1). What’s more, the aspirations of teenagers are important predictors of adult attainment: both educational and occupational. Consequently, our findings indicate that low aspirations can lead to stalled social mobility, over and above innate ability or financial barriers.

We discovered this by linking occupational status to data on occupational aspirations and labour market outcomes of the 1958 UK cohort of the National Child Development Study.

The downside of ‘big dreams’

In addition to the potentially positive effects of ‘big dreams’, ambitious goals can also lead to disappointment. Wellbeing questions in the National Child Development Study allowed us to test for this. We found evidence for negative effects of aspirations-achievement gaps when aspired occupational status is not reached. This highlights the potential costs of pushing certain children to aim high.

However, we also know that as attainment is closely linked to socioeconomic status. These young people face greater barriers to achieving ambitious career goals compared to students from more privileged backgrounds, so alongside this we should also be looking at how we address these barriers.

How do parents’ aspirations impact their children?

We also looked at the career aspirations of parents and teachers. In particular, we studied whether young people perceive it as a pressure or a motivation when their parents’ career aspirations exceed their own.

There is a strong correlation between parental and child aspirations. Yet we found that a big gap between children’s aspirations and what their parents aspire for them might negatively affect children’s wellbeing in early adulthood.

Failing to recognise the role of educational and occupational aspirations in driving success in both school and life outcomes is a lost opportunity to reduce social inequality. Policy actions aiming to raise aspirations, particularly among disadvantaged children, can have a sizeable impact on reducing intergenerational inequality.

However, we would also caution that any policy intervention aimed at increasing children’s aspirations should also recognise the trade-off between aspirations and life-time wellbeing.

Figure 1: Comparison between intergenerational mobility calculated based on either achieved or aspired occupation

The first graph revisits the results widely known in the intergenerational inequality literature of limited mobility that children are more likely to remain at the occupation position similar to parents – with higher prevalence among lowest socioeconomic background. Strikingly, as we can see in the second graph, even for their aspirations, children from lower family background limit their career goals to low-rank occupations.