This week’s blog is from Christian Krekel, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics. In this blog, Christian outlines the wellbeing benefits of hosting the 2012 London Olympics.

To host the Olympic Games, governments are willing to spend billions of taxpayers’ money, despite the fact that most academic studies find little or, if anything, mixed evidence on the economic impacts of hosting (examples here, here, here, here, and here). This has led many governments to argue in favour of intangible wellbeing benefits when making the case for hosting.

The UK government’s assessment of the 2012 Olympics in London, for example, featured, amongst other things, intangibles such as:

- inspiring a generation of children and young people

- community engagement

- enthusiasm for volunteering

In the same vein, the notion of legacy has become increasingly important when making the case for hosting: for the 2012 Olympics in London, the Final Report of the International Olympic Committee Coordination Commission mentioned the word ‘legacy’ no less than 90 times in its 127-page report.

While the intangible wellbeing benefits of hosting get considerably less attention in the academic literature, our research finds that these benefits can be substantial: in the case of the 2012 Olympics in London, they may – although only short-lived – justify the costs of hosting, which were estimated to be approximately £9.3 billion.

The fact that impacts on wellbeing varied little by medal wins suggests that the positive atmosphere surrounding the hosting of the event itself, as evidenced by, for example, stronger wellbeing impacts around the opening and closing ceremonies, matters most.

Life satisfaction of Londoners increased significantly and strongly

To study the intangible wellbeing benefits of hosting, we looked at the example of the 2012 Olympics in London. We compared the wellbeing of Londoners during the summer months of 2011, 2012, the year of the event itself, and 2013 with that of residents in Paris and Berlin – two large European cities which had about the same trend in wellbeing prior to the event.

Taken together, we followed more than 26,000 individuals in London, Paris, and Berlin over time, collecting rich data on their behaviour and wellbeing as well as on their personal background characteristics.

Our main outcome is self-reported life satisfaction, which asks respondents: “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?” Answer possibilities range from zero “not at all” to ten “completely”.

We also collected data on living conditions in the three cities during the study period, including data on:

- weather – temperature and precipitation

- the economy – unemployment rates and average incomes.

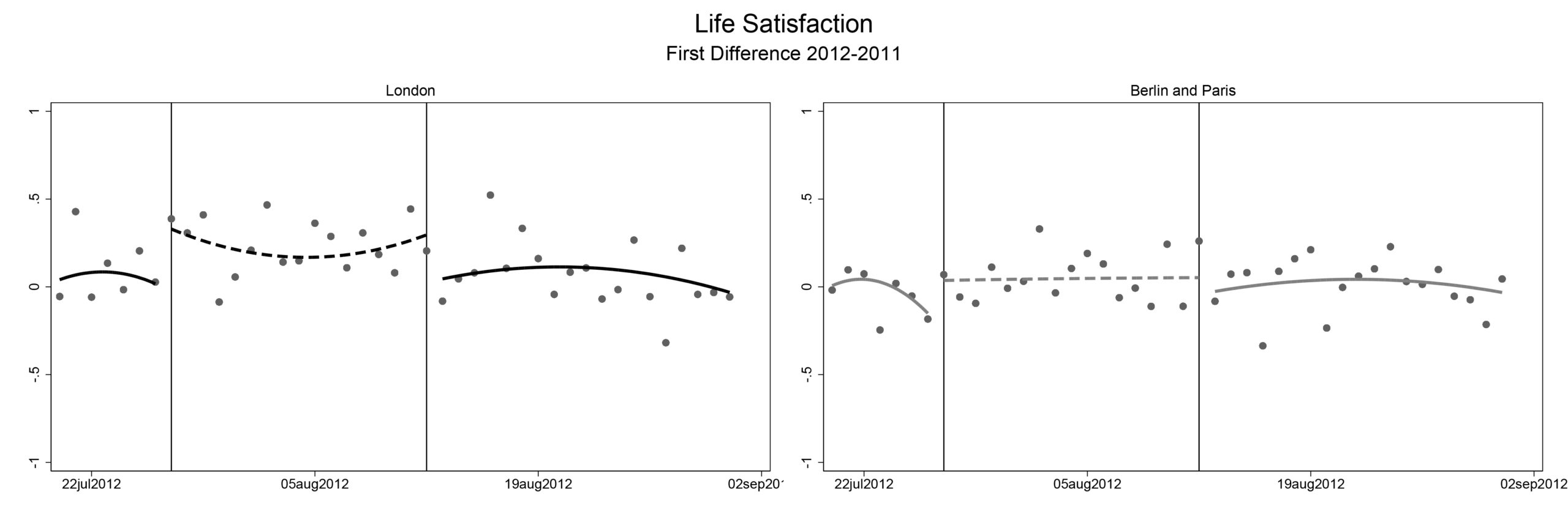

Figure 1: Life satisfaction, first difference 2011-2012

Figure 1 shows the central result of our study: it plots the difference in daily average life satisfaction between 2011 and 2012 for London compared to Paris and Berlin, pooled together; the vertical lines mark the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2012 Olympics in London.

While there are little differences in the periods before and after the event, there is a clear difference in daily average life satisfaction during the time of the event, especially around the opening and closing ceremonies, with Londoners reporting a significant, strong increase in life satisfaction relative to Parisians and Berliners. This impact, however, does not last very long: there is almost an immediate return to baseline after the event. In 2013, one year after, no legacy effects in terms of wellbeing can be detected.

Note that, at the time of the event, there were no other, potentially confounding events in either city that could explain our finding for life satisfaction. It also holds regardless of whether we control for differences in personal background characteristics of respondents or differences in living conditions between cities. Finally, our finding sustains a range of robustness checks, including placebo tests that exploit both placebo outcomes and time periods.

Was hosting worth the costs?

Trading off the effect of hosting on life satisfaction with that of income, we find that the average resident in London would be willing to pay between £270 and £892 (depending on model) to host the Olympics, yielding an aggregate willingness-to-pay between £2.2 billion and £7.4 billion in London – well below the actual costs of hosting (£9.3 billion). Considering the impact on Londoners alone, therefore, suggests that hosting was probably not worth it.

But it is unlikely that the event left everybody else in the country completely unaffected. Unfortunately, our research design cannot account for the impact on the rest of the UK. We can, however, ask: by how much would the impact on Londoners have needed to spill over to the rest of the UK in order to make the Olympics a worthwhile endeavour?

Our most conservative estimate suggests a break-even multiplier of around 0.5. This means that, as long as the impact on the rest of the UK would have been greater than half the impact on Londoners, the wellbeing impact of hosting the 2012 Olympics in London did justify the costs. It turns out that this is not unrealistic: Atkinson et al. (2008) asked respondents in places across the UK directly about their willingness-to-pay in order to host the event, showing that the willingness-to-pay outside of London was, on average, about half of that in London.

Considering our estimated willingness-to-pay and multiplier for the national wellbeing effect required to make hosting the Olympics worthwhile, a case can be made that the wellbeing impact of hosting the 2012 Olympics in London was actually worth the costs.

Response from Ruth Hollis, Director of Policy and Impact at Spirit of 2012

Dr Christian Krekel of the LSE asks whether the Olympic Games are worth hosting. He found that Londoners’ life satisfaction increased significantly and strongly during the summer of 2012 in comparison with adjacent years, and with that of Parisians and Berliners.

This comes as no surprise to us at Spirit. Indeed, that national ‘feel good factor’ inspired the then Big Lottery Fund to found us as an independent trust to keep that Spirit alive, and to rekindle it around other national events not just in London but across the UK. The challenge for us is to sustain that wellbeing benefit beyond the event and the immediate geography.

Spirit looks for ways of ‘bottling’ that feel-good surge so that people who may not identify with national mega events can benefit from feeling more connected with each other and the places where they live. Inspired by the Glasgow Commonwealth Games our Fourteen programme empowered communities to decide how they wanted to increase participation in physical activity, culture and volunteering. Fourteen took that spirit of Glasgow 2014 into the heart of neighbourhoods, not just in Scotland but in all four Home Nations. Thousands of people felt empowered and proud of their connection to a major national event, and their wellbeing increased as a result.

In Northern Ireland a survey of 4,000 participants showed an 11% rise in those reporting higher levels of life satisfaction, and across the UK significantly fewer people reported feeling detached from their local communities, with one community volunteer saying, “There are so many people engaged now in a way that there never were previously”.

Five years on Spirit is still investing in the health and wellbeing of the people of Scotland, in partnership with the Scottish Government. Hosting the Glasgow Games inspired the Scottish Government to create a new national physical activity strategy to tackle sedentariness – a principal cause of ill health and premature mortality – and catalysed an international elite sporting event into a movement with a lasting impact on the lives of some of people of all ages in communities with endemic health and wellbeing inequalities. The Scottish Government asked Spirit to manage these initiatives and we have consistently monitored the 25 projects using the ONS4 measures. They are showing demonstrable wellbeing benefits – in the recent Sporting Equality Fund the average life satisfaction level of the participants was 6.8 out of 10. By the end of the project, this average had risen to 8.0 out of 10.

This is a great illustration of how a sporting mega event can inspire new thinking and investment in beneficial social change. It begins with the stadia, the ceremonies and the sports stars, but with thought and long-term investment coming in behind, we are proving that events like the Olympics can inspire and help sustain longer lasting and wider reaching changes in people’s happiness, pride and sense of self-worth.

The Olympic and Paralympic Games cost billions and attract vast global audiences. Spirit’s community investment, although event inspired, is very different – it is local and participatory, rather than spectacular. It is low cost. And it is worth it. We have evidence that mega-event inspired ‘micro-events’, particularly if they engage people over months rather than days, can have significant impact on wellbeing that is palpable and profound.

References

1 Atkinson, G., S. Mourato, S. Szymanski, and E. Ozdemiroglu, “Are We Willing to Pay Enough to ‘Back the Bid’?: Valuing the Intangible Impacts of London’s Bid to Host the 2012 Summer Olympic Games,” Urban Studies, 45(2), 419-444, 2008.

2 Baade, R., and V. Matheson, “Bidding for the Olympics: Fool’s Gold?,” in: Barros, C., M. Ibrahim, and S. Szymanski (eds), Transatlantic Sport, London: Edward Elgar, 2002.

3 Baade, R., and V. Matheson, “Going for the Gold: The Economics of the Olympics,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(2), 201-218, 2016.

4 Billings, S. B., and J. S. Holladay, “Should Cities Go for the Gold? The Long-Term Impacts of Hosting the Olympics,” Economic Inquiry, 50(3), 754-772, 2012.

5 Coates, D., and B. Humphreys, “The growth effects of sport franchises, stadia, and arenas,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 18(4), 601-624, 1999.

6 Coates, D., and B. Humphreys, “The effect of professional sports on earnings and employment in the services and retail sectors in US cities,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, 33(2), 175-198, 2003.

7 Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Post Games evaluation: Meta-evaluation of the impacts and legacy of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, 2013.

8 Dolan, P., G. Kavetsos, C. Krekel, D. Mavridis, R. Metcalfe, C. Senik, S. Szymanski, and N. R. Ziebarth, “Quantifying the Intangible Impact of the Olympics Using Subjective Well-Being Data,” revised paper, 2019. Online

9 National Audit Office, The London 2012 Olympic Games and Paralympic Games: Post-Games review, 2012.

10 Greater London Authority, “GLA Household Income Estimates”, Online.

11 Stevenson, B., and J. Wolfers, “Income, Growth, and Subjective Well-Being,” in: Development Challenges in a Post-Crisis World, World Bank: Washington, DC, 2010.