For high performance to be sustainable, we need achievement, meaning, enjoyment and learning. Yet most of us will know what it feels like to get to the end of a working day and feel absolutely frazzled. Emotionally exhausted, perhaps a bit cynical and still – despite a long slog – feeling like you haven’t even been that productive.

When feeling frazzled turns into burnout

When workplace stress becomes chronic and is not managed, these warning signs – emotional exhaustion, cynicism and reduced personal accomplishment – lead to what is known as ‘burnout’.

Burnout – an occupational phenomenon rather than a medical condition – dates back to the 1970s and has since been found across a range of professions including in health, social care, law enforcement and education.

The implications of burnout are significant – both for the individual in terms of poorer health, and the employer through higher turnover and poorer organisational performance. Last year, for example, an estimated 12.8 million working days were lost due to work-related stress, depression or anxiety.

In the news, burnout is increasingly being discussed as a public health crisis, and the current coronavirus outbreak is raising concerns about an increased risk of burnout among workers, particularly those in front-line positions and in healthcare.

Applying behavioural insights to reduce burnout in 911 call handlers

At The Behavioural Insights Team we apply the science of human behaviour to overcome complex policy challenges and achieve positive social impact. We use behavioural insights – from academia and practitioners – to explore challenges, develop solutions, and rigorously test what works.

We recently carried out an ambitious project together with the University of California, Berkeley, to develop and test an intervention to reduce burnout among 911 call handlers in nine US cities. 911 call handlers respond to emergency calls and deal with demanding situations every day, and their emotionally taxing work can lead to burnout, absenteeism and high turnover.

Our intervention focussed on strengthening social belonging and support to reduce loss in purpose and identity as well as burnout and turnover. The project involved sending six emails outlining success stories and positive reflections previously shared by 911 call handlers themselves. These emails were delivered over six weeks to the 911 workforce and aimed to foster a collective sense of professional identity and to recognise the value and skills of 911 call takers.

“Yes, what we do can be very stressful, sad, and some calls are seemingly unbearable, but what other job allows you to just listen, type, and save a life? Not many.”

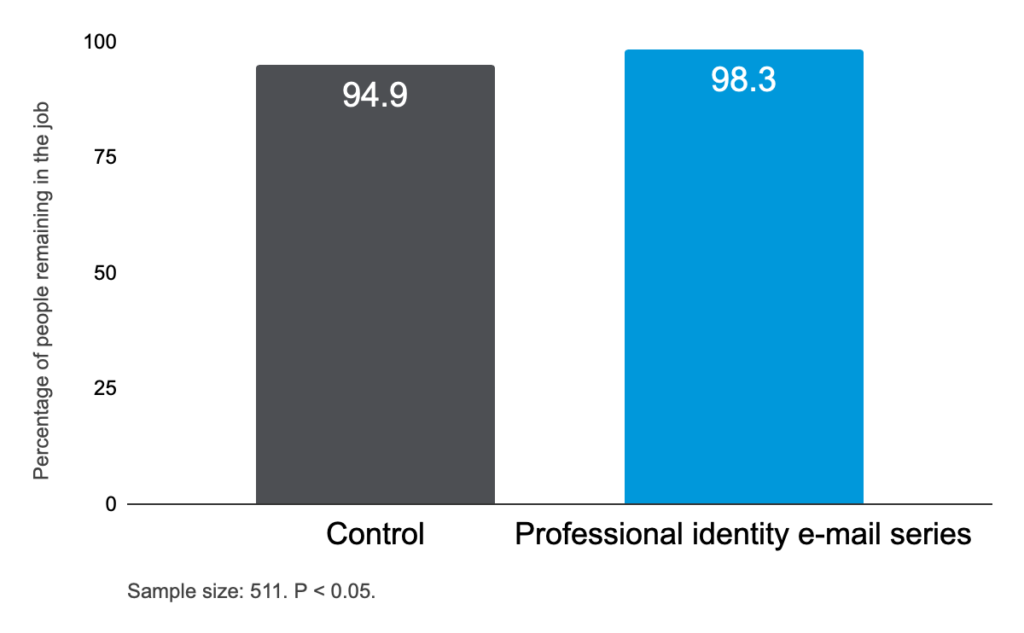

Our simple email intervention led to a 16% reduction in burnout on the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI), and halved resignations in the post-intervention period. The intervention did not have an effect on the amount of sick leave taken.

Percentage of people staying in their job

What can employers do to help protect against burnout?

In the context of the coronavirus outbreak, some people are likely to be experiencing greater workplace stress and home life disruption, and so the threat of burnout could rise over the coming months. There are some things employers can and should do to support their workforce in this pandemic:

- Recognise: It is important for employers to recognise that the current crisis context has increased people’s workload and the emotional burden they carry outside of work as well, which can contribute to burnout. Showing an understanding for employees’ difficulties due to the crisis can open the door to discuss how best to support them.

- Learn: At a more fundamental level, employers should familiarise themselves with the evidence on what works to improve wellbeing. Factors such as maintaining active communication with workers, ensuring reasonable workloads, and proactively providing management support can reduce the risk of burnout.

- Explore: Employers should keep track of the wellbeing of employees to identify potential emerging issues and teams that may need special attention. Short, repeated surveys can help employers get valuable information about the overall wellbeing trends amongst their workers, the emergence of hotspots or red flags, and how these evolve over time.

- Implement: Our 911 trial demonstrates that sometimes even light-touch interventions can improve employee wellbeing and have a positive impact on organisations. Test out small interventions based on the evidence you collect on what works to improve wellbeing and evaluate their impact using a short survey.

We are currently carrying out research to explore whether text messages aimed at boosting wellbeing can reduce burnout in the UK and we will share our results when we have them.

If you want to find out more about this project, or any of our other work applying behavioural insights to wellbeing, please get in touch.