Can a local community course improve mental wellbeing and social connection? New RCT findings

There is a growing evidence base on how place-based interventions can impact our wellbeing, including this evidence review from the Centre. Wellbeing is not a silver bullet, but we know that personal wellbeing, social connection, agency and purpose all matter. Our evidence review in 2018 found that:

- Community hubs can promote social cohesion, by bringing together different social or generational groups; increase social capital and build trust; increase wider social networks and interaction between community members; and increase individual’s knowledge or skills.

- Interventions that provide a focal point, or targeted group activity, may help to: promote social cohesion between different groups; and overcome barriers that may prevent some people (in marginalised groups) from taking part

We conducted a Randomised Controlled Trial to evaluate the impact of Action for Happiness’ Exploring What Matters course. This is a local community intervention aimed at raising general adult population mental wellbeing, social connections and pro-sociality. Pro sociality is helping others including empathy, kindness and taking action to make a difference. It does this by bringing together participants in weekly face-to-face groups to discuss what matters for a happy, meaningful life. The course is run by volunteers in their local communities, and is currently conducted in more than 19 countries around the world.

Key findings

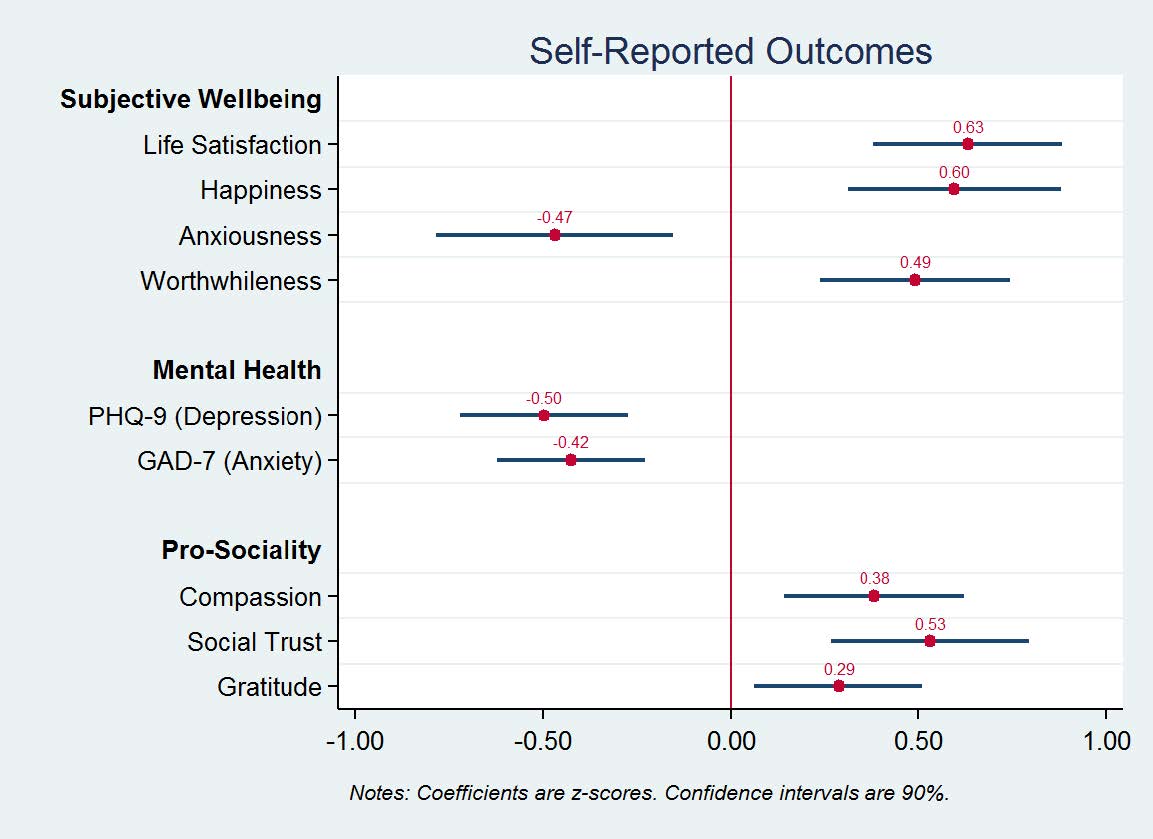

The course significantly increased subjective wellbeing measures in:

- life satisfaction by 63% of a standard deviation

- happiness by 60%

- worthwhileness by 49%

While anxiousness significantly decreased by 47%.

The effect of the course on self-reported outcomes for subjective wellbeing, mental health, and pro-sociality are large.

The effect on life satisfaction, for example, is larger than being partnered as opposed to being single. And only slightly less than being employed as opposed to being unemployed (Layard, 2019).

There is some evidence that effects are sustained (or even enhanced) two months after participation.

An analysis of mechanisms suggests that, while the socialising aspect of the course is important, effects on participants mostly come about through changes in information and subsequent behaviour.

Impacts on biological outcomes are less clear.

Although we do not find significant average effects, there is some evidence that, for specific sub-groups, levels of IL-6 – a pro-inflammatory cytokine associated with depression – are reduced. One reason why we fail to find significant average effects may be the composition of our sample: high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are typically found for major depression; respondents in our sample, however, report, on average, only a mild depressive symptoms, pre-treatment.

Design of the RCT

To account for self-selection of participants onto the course, we use the fact that the course is over-subscribed (ratio of one to three) and employ a waitlist randomisation design. After registering for the course online, participants are first randomly allocated to either treatment or control group. They are then invited to arrive on the same day to have their baseline data collected. Only participants in the treatment group start their course that day, whereas those in the control group start theirs later, after the treatment group has finished. Randomisation ensures that observable and unobservable characteristics are balanced between treatment and control group.

*Take a look at Test, Learn, Adapt: Developing Public Policy with Randomised Controlled Trials.

We collected data on two categories of outcomes:

- Self-reported outcomes come from survey data, which include items on

- subjective wellbeing

- mental health

- pro-sociality

- Biological outcomes come from biomarkers collected through saliva samples, which include

- cortisol – a steroid hormone responsive to stress

- a range of cytokines – immune proteins involved in inflammatory response.

Next steps

- Looking at long-term impacts that go beyond two months post-treatment. Seemingly small, one-off, social psychological interventions have been found to initiate positive behavioural change that may sustain or even reinforce itself over long periods of time.

- Looking at behavioural spillovers from one life domain to another, for example, whether higher personal wellbeing leads to more pro-social behaviour. Likewise, it may be interesting to look at different types of behavioural outcomes, in particular those in the area of revealed preferences.

- A larger sample size could help stratify results by demographics and other participant characteristics. This could provide useful insights into differential impacts in these areas. This could help targeting particular groups of people more effectively.

- Studying the causal effect of the course on facilitators (i.e. the volunteers who lead the course) would be a promising avenue for future research. This is motivated by the growing literature on mentoring and advice-giving in social psychology.

Measure your charity's wellbeing

Try our guidance to measure your wellbeing impact