Many organisations and employers know the wellbeing value of providing their employees with quality jobs and good working conditions. The difficult part is knowing how to put this evidence into practice, that is, identifying what are the workplace interventions that work and how they should be implemented to get the maximum wellbeing and financial value out of them.

Although the evaluation evidence about what actually works is still emerging and implementing big changes can be risky and expensive – especially in these uncertain times – there are some simple actions employers can take, such as treating employees with fairness, that can have a huge effect on their happiness and motivation to work.

The Nobel prize economist Daniel Kahneman demonstrated that one of the ways people seek to maximise their wellbeing is by comparing their outcomes with those of their reference group. In other words, people get more wellbeing not necessarily from maximising their own profit but from judging their utility as fair compared to others, and this is what underpins many of the decisions we make. The difference between our outcome and others’ can be a strong predictor of life satisfaction.

Many studies on job quality build on this theory by asserting that a good job is not only one that provides a certain absolute level of earnings but also one with a fairly determined wage system. Indicators of fair wage could be, for instance, to be paid:

- In accordance to one’s effort (hours of work and intensity), skill, responsibility, outcomes, and risk-taking; and

- In accordance with the reward received by others doing the same job in similar circumstances.

However, measuring the fairness of salary is far from simple and that’s probably one of the reasons why this aspect of job quality often gets forgotten.

A recently published study reminds us about the importance of fairness and equality of rewards to improve workers’ wellbeing as well as their performance.

Is the motivation to work for rewards influenced by unfairness and the relative value the rewards offered?

Researchers at the Affective Brain Lab, University College London and Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford, conducted a psychological experiment with an online labour market platform to answer this question. They thought that unfair rewards would not only make people unhappy (as Kahneman had found) but would also affect their motivation to work for further rewards. To that aim, they examined participants’ willingness to complete a simple transcribing task in exchange for a monetary reward, “while observing the rewards offered to others for completing the same task”.

The rewards presented to participants varied in terms of:

- unfairness (high or low inequality of all rewards in the group)

- rank (5th, 4th, 3rd, 2nd or 1st best-offered reward)

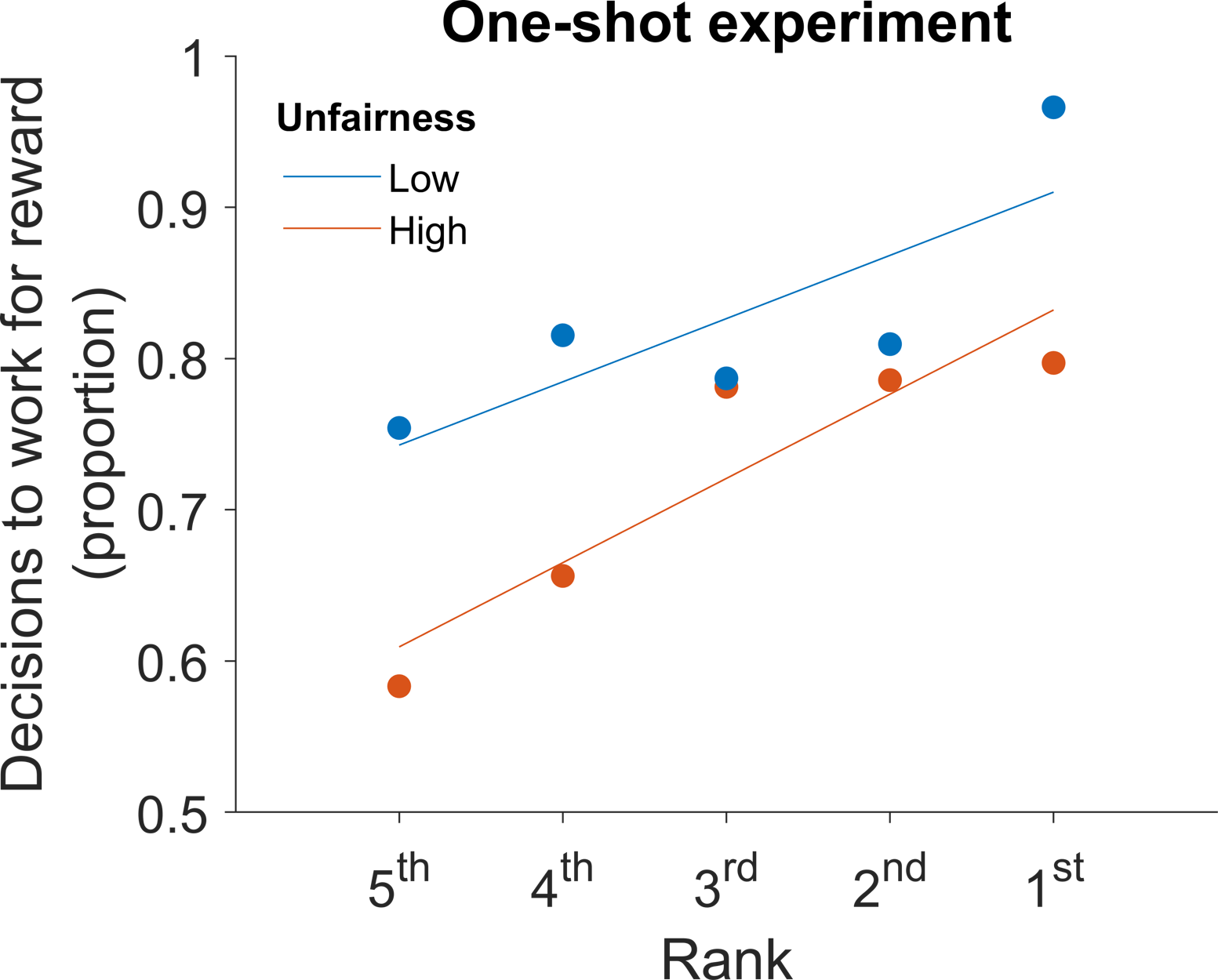

As illustrated in Figure 1, researchers found that, despite the same level of absolute reward, participants were less willing to work for a reward of £0.24 when they believed that:

- The distribution of offered rewards was unfair (red) than when it was fair (blue);

- The rank of their reward was lower.

Figure 1. Motivation to work by rank and fairness of offered reward. Each dot represents the proportion of participants who decided to perform an additional task for a bonus reward of £0.24.

What’s more, the results of the experiment indicated that unfairness does not only discourage those who are offered the lowest rewards but also those who could consider themselves luckier.

How does unfairness influence motivation?

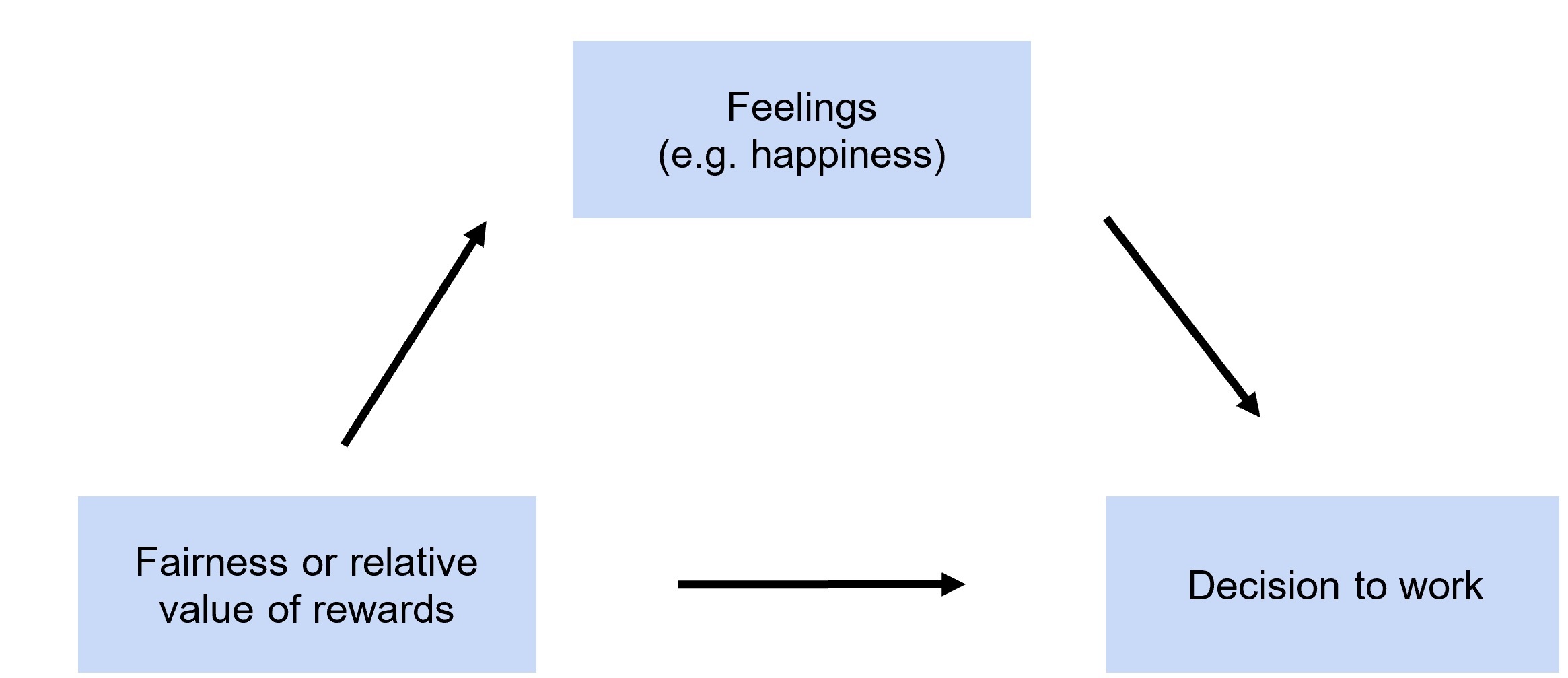

Gathering additional information about participants’ feelings after seeing the distribution of rewards, the researchers found that although the rank and fairness of rewards had a direct effect on making people more willing to work, part of this motivation also came from the fact that fairness and getting a relatively better reward makes people happier, which in turn is more motivating.

Figure 2. A simplified scheme of the effects of fairness and relative value of rewards on motivation to work.

These findings sit well with the growing evidence about the effects of employees’ happiness on productivity and performance. In a study among BT call centre workers, it was shown that they “make around 13% more sales in weeks where they report being happy compared to weeks when they are unhappy.”

It would be interesting to explore if the practical application of these results extends beyond the fairness in the wage system to, for instance, the fairness in contractual arrangements, allocation of employee non-monetary benefits, determination of job content, opportunities to be involved in decision making, training provision and even in terms of treatment from colleagues and managers.

Keeping our workforce motivated can be an even more difficult task at times when many feel that going to work can be risky for their own or their families’ health, or when many others continue to work from home, distant from their colleagues and juggling care responsibilities. The evidence now provides us with some clues about what can be done to keep their spirits up.

Support your team's wellbeing

Get our 12-week special email series: one email a week packed with evidence and insights on maintaining employee wellbeing, and supporting adaptation to the new realities of working during the pandemic.