Today we publish our latest evidence review that looks at the links between mental health issues or low wellbeing, and finding and keeping jobs. The review authors*, part of our work and learning evidence programme, share the key findings and policy implications.

Whether we are employed or not has an impact on our wellbeing, as does the quality of our work. But what is the impact of wellbeing upon transitions into – and out of – work? Are people with lower wellbeing more likely to lose their jobs, or move into long-term sick-leave, care or early retirement? Are they less likely to get back into work if unemployed?

This new review of evidence shows that people with poor mental health, especially young adults, are at greater risk of being out of work involuntarily, for example sick leave or early retirement. What’s more, having mental health issues can reduce the possibility of finding work, as well as hindering people already in employment from keeping their jobs. This is the case regardless of whether it is full- or part-time employment.

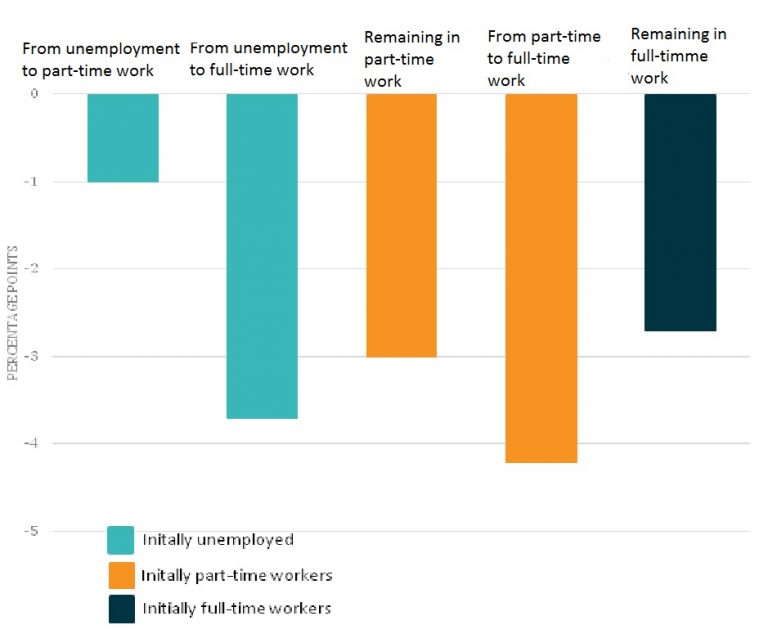

The graph below shows that those with mental health conditions have a lower probability of staying in work and moving from unemployment into work. The difference is only related to the mental health condition: which means this is the case even when all other factors such as income, age, gender, education, ethnicity and marital status are the same, or ‘held constant’.

Source: Baldwin, M.L.M., Steven C. (2014) p. 332-344.

This overarching discrepancy is not new to many policymakers and practitioners. Past research has looked at some of the potential channels, including the stigma surrounding mental health issues. However, this is the first review to look at the effect of wellbeing on being out of work (whether due to unemployment, on sick leave, early retirement or a number of other reasons), with a focus on the causal impact draws together dispersed cases and evidence from across the developed world. Drawing together the evidence can give us greater confidence of whether there are generalisable messages and trends, the differences in contexts and the types of approaches decision-makers should be looking into.

Much of the evidence in this review is promising or initial rather than strong. This reflects the relatively small number of studies conducted and that it is difficult to isolate wellbeing as a direct cause of moving into or out of work. For example, although not something explicitly explored in the review, wellbeing is often linked to other changes, such as family circumstances, which can influence wellbeing and employment at the same time.

The evidence points to unemployment policies and practices that improve emotional and practical support given to job seekers.

One notable gap in the evidence base appears to be research into the effect of political and legal actions – for example, the Equality Act – on the employment levels of those with mental health problems.

And the messages for researchers? Future research should prioritise multiple measures of wellbeing together with longer follow-up periods. Studies which were conducted over a short time period were less likely to report significant effects than those with longer follow-up periods. There may be a long lead time between a change in wellbeing and a change in employment or being out of work. Similarly, those which investigated the link between a very specific measure of mental health were less likely to find an effect than those using broader or multiple measures.

Report authors are: Cigdem Gedikli, University of East Anglia; Mark Bryan, University of Sheffield; Sara Connolly, University of East Anglia; David Watson, University of East Anglia; Abasiama Etuknwa, University of East Anglia; Oluwafunmilayo Vaughn, University of East Anglia