How has Covid-19 affected wellbeing across the world?

From the Centre: This research provides a snapshot of some people’s Covid-19 related experiences, but is not representative of the general population. The survey sample included 3,000 people from 97 diverse countries that experienced different levels of infection and policy responses. People were voluntarily recruited to answer the survey by the Happiness Institute through their existing network and audience. Respondents were predominantly female (83%) and mostly between the ages of 25-34 (32%) and 35- 44 (25%)

To understand how the Covid-19 pandemic has impacted subjective wellbeing, the Happiness Research Institute recently published a report ‘Wellbeing in the age of Covid-19’ summarising findings of a longitudinal study of 3,211 people that were surveyed up to six times between April to July 2020.

As several large-scale studies in the UK, Germany, and Canada have shown, the pandemic has clearly affected life satisfaction. Eurofound data shows that average life satisfaction has significantly dropped across European countries, in some cases as much as 17%, which is equivalent of the wellbeing effect of being diagnosed with depression.

With this in mind, the intention of our report was to provide deeper insight into how subjective wellbeing evolved throughout the first phase of the pandemic. By regularly asking our respondents about their weekly emotions, loneliness, worries and behavioural changes, we were able to highlight some of the most important dynamics affecting evaluative, affective, and eudaimonic wellbeing.

Key findings

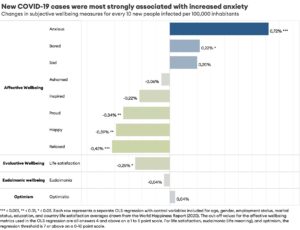

COVID-19 case increases most strongly associated with affective wellbeing

Using OLS regression analysis, we confirmed that the number of COVID-19 cases within a given country is strongly associated with negative emotions. Most striking was the impact of case increases on anxiety. For a given population of one million, only 100 new COVID-19 cases would lead to 7200 more people becoming anxious. On the other hand, life satisfaction and eudaemonia were relatively less affected by rising COVID-19 cases.

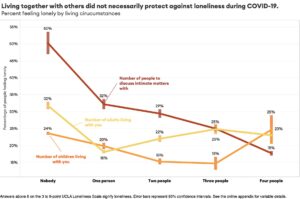

Cohabitation did not necessarily protect against loneliness

Similar to What Works Wellbeing’s study on loneliness, we found that groups that were particularly vulnerable to isolation before Covid-19, were most likely to report high levels of loneliness after the pandemic began to take root. Young people, and those without jobs or partners were found to be the loneliest.

The relationship between cohabitation and loneliness on the other hand proved to be more complicated. While those who live alone were more likely to be lonely than those who did not, individuals who lived with more than one adult or more than three children seemed to be even lonelier than those who lived with only one adult or fewer children.

Perhaps the most important takeaway from this is that having more social contacts seemed to make the biggest difference in reducing loneliness levels, not necessarily living with more people. In fact, living with more people can even predict higher levels of loneliness in some cases, not less.

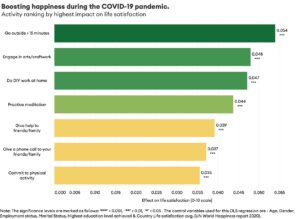

Behavioural changes helped in offsetting drops in life satisfaction

Encouragingly, many of the common activities that respondents took up during lockdown seemed to have the largest positive impact on life satisfaction. Our data suggests that, at least at first, people adapted relatively well to the constraints that were placed upon them.

The figure below shows the life satisfaction impact of increasing an activity during the pandemic. For example, spending at least 15 minutes outside for one more day per week was associated with a 0.054-point increase in life satisfaction on a 0 to 10-point scale. Calling with loved ones and exercising also had significant impacts on subjective wellbeing and were quite common within our sample population.

Using evidence effectively

As we continue to face the Covid-19 pandemic, it is important for policymakers to learn from evidence-based studies on the pandemic’s wellbeing impact and to pay closer attention to our mental as well as our physical health.