Understanding student wellbeing: insights from latest analysis

We know that having a job – and the quality of that job – matters. One way we can support this is through higher education, which can improve someone’s employment opportunities through gaining new experiences and formal qualifications. Understanding the drivers and determinants of student wellbeing will not only help them thrive during their studies, but also establish the foundations for lifelong learning and their future wellbeing.

Here, we introduce two newly published reports by Evidence Associate Michael Sanders analysing the wellbeing and mental health of students in higher education at undergraduate, taught postgraduate and doctorate levels.

Undergraduate and taught postgraduate students

Student Academic Experience Survey (SAES) data 2017-2021 was analysed to examine:

- How the wellbeing of undergraduate and taught postgraduate students has changed over time.

- How it varies according to demographic characteristics and circumstances including contact hours and employment status.

The survey has collected data on undergraduate students’ wellbeing since the 2011-2012 academic year. It uses the Office of National Statistics’ ONS4, as well as other measures that capture details of students’ lives on and off campus.

Insights

The report considers wellbeing over time, comparing 2019-2020 with 2020-2021 data to show student wellbeing was adversely affected by the Coronavirus pandemic and has yet to fully recover.

Potential relationships between wellbeing and contact hours, economic background, employment, residence, ethnicity, family education level, proximity to university, and disability were also explored.

There were some stronger relationships found in the data, suggesting a potential association between wellbeing and specific circumstances or characteristics including:

- Students living in halls of residence or shared flats

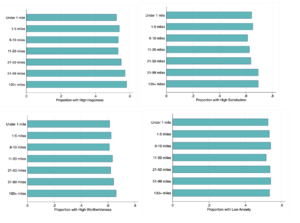

- Commuting distance

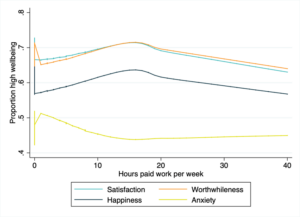

- Paid employment

- Contact hours

Percentage of high happiness, life satisfaction and worthwhile scores, and low

anxiety scores by distance travelled to university

Relationship between high subjective wellbeing and hours worked

Next steps:

- Use this data to further understanding of how best to provide support.

- Continue to gather, track and explore student wellbeing data.

- Identify and test interventions that could help different groups.

- Monitor trends in student wellbeing and what they might mean for student support.

Find out more in the full report.

Postgraduate research students

Between June and September 2023, a quantitative survey was conducted to understand the lived experience and wellbeing of UK doctoral students. It was completed by 108 respondents and included measures of happiness, life satisfaction, sense that life is worthwhile, and anxiety (ONS4) The analysis looked at overall wellbeing, and how it varies by age, Year of PhD, gender, and parents’ highest levels of education.

It also looked at measures of burn-out – chronic workplace stress – as well as students’ perceived self-efficacy, the extent to which they feel they are able to have an impact on the world, and that they feel capable, competent and useful.

Insights:

- Postgraduate research students have worse wellbeing in general than those in taught programmes.

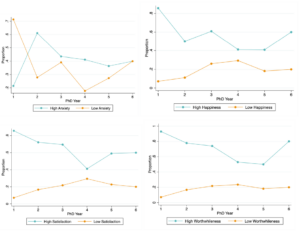

- Wellbeing worsens throughout studies – students in their second year and beyond have substantially lower wellbeing and self-efficacy, and higher anxiety and burnout than those in their first year. This aligns with existing evidence indicating qualifications can improve life satisfaction and happiness up to masters level but that over-qualification can also lead to reduced wellbeing in the job market and ‘frustrated achievers’.

Proportion of high and low response on ONS4 over PhD Year

- Age is a protective factor for wellbeing – older students reporting higher wellbeing and lower anxiety than younger students overall. Likewise, burnout shows a pattern of decline over student age.

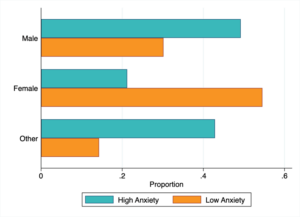

- Male postgraduate research students report higher burnout than female students on average, and are more likely to report high anxiety scores.

Proportions of high responses on Anxiety by sex.

In addition to the quantitative survey, students were also asked qualitative questions about their experiences. From their responses, four main themes were identified:

- Finance – respondents reported financial struggles as a perceived stressor and barrier.

- Supervision – respondents identified tensions between students and supervisors in terms of expectations, priorities and availability, as well as a lack of perceived supervisor expertise.

- The dichotomy of a PhD – respondents commented on the difficulty of balancing a PhD with their wider responsibilities, and that they are neither a full member of the faculty, nor a student in the way that that word is widely understood.

- Positives – respondents identified finding friends and co-authors among their cohort, being able to research something that they were passionate about, and good supervisory relationships as positive experiences.

Next steps

This analysis is an encouraging step towards a more representative picture of the wellbeing of doctoral students. Next steps include:

- Further research to confirm our findings in a larger sample, leading to addressing the challenge of low wellbeing at a policy level.

- Given their responsibilities of research and teaching, it would also be valuable to understand postgraduate research students’ wellbeing in the context of occupational data.

If we can diversify our doctoral cohorts, and ensure that students at this level thrive, we can diversify the more senior levels of academia. This has knock-on effects on the shape of future research fields, and for the ability of undergraduate and masters students to see themselves represented in their lecturers.

Find out more in the full report.

Explore our Student mental health and wellbeing project.