Understanding the links between children’s mental health and socio-economic status

There is growing concern about the mental health of children in the UK (see Department for Health/ Department for Education, 2017). This has led to efforts to identify groups of children who are at higher risk of mental health problems. Our understanding has, however, been hampered by apparent contradictions in recent research. For example, a recent NHS survey reported higher rates of mental disorder in children who lived in low-income households or with a parent receiving income related benefits. In contrast, a 2019 Department for Education report found that teenage girls from more disadvantaged backgrounds reported better psychological health. What is the reason for these disparities in the evidence?

The Good Childhood Report 2018 suggested that these different conclusions are partly related to using different measures of mental health. The sixth sweep of the Millennium Cohort Study, conducted with children aged around 14 years, contains:

- A measure of children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBDs), designed to measure emotional symptoms, peer problems, conduct disorders, hyperactivity/inattention, and pro-social behaviour, reported by parents

- A measure of depressive symptoms reported by children, statements about the last two weeks, such as ‘I didn’t enjoy anything at all’.

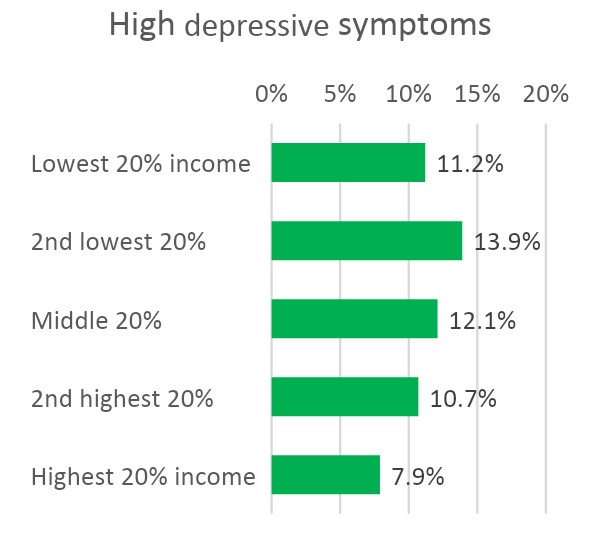

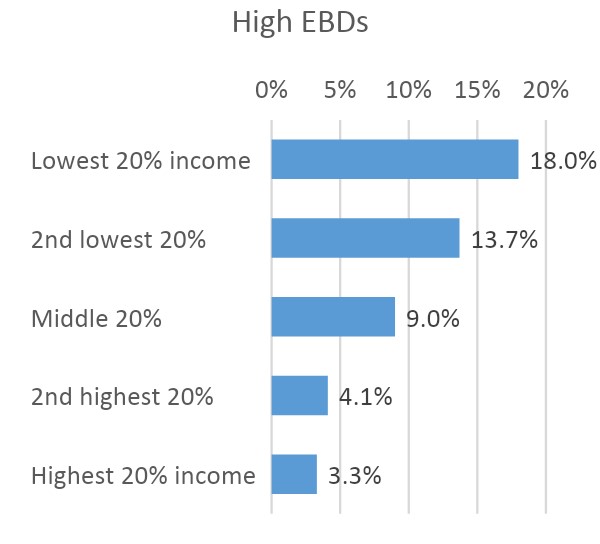

Our analysis (Figure 1) showed:

- A clear relationship between household income and emotional and behavioural difficulties. Children in lower income households were more likely to have high emotional and behavioural difficulties.

- A less clear link between household income and children’s depression.

Figure 1: Variations in high depressive symptoms and high emotional and behavioural difficulties by children’s characteristics

Source: Millennium Cohort Study, Wave 6, 2015 (when children were aged 14). Note: The figures show average marginal effects from logistic regressions with the heading measures as a dependent variable and children’s characteristics and circumstances, including income, as independent variables.

Analysis in The Good Childhood Report 2019 also highlighted the importance of the poverty measure/s used. Financial strain (reported by the parent) was more strongly related to children’s depressive symptoms than household income was. Other evidence (see, for example, Main and Pople, 2012), suggests that children’s direct experiences of deprivation may affect their wellbeing much more than objective measures of their family economic status.

Our analysis also shows the importance of measuring a range of mental health issues. Children’s depression at 14 years old is much more strongly connected with self-harming (see Figure 2) than whether they have emotional and behavioural difficulties.

Figure 2: Self-harm by low and high mental health measures

Source: Millennium Cohort Study, Wave 6, 2015 (when children were aged 14).

Clearer language, better measures

These differences show the importance of using clear language/definitions when discussing poverty and mental health. We need to consider which measure/s of socio-economic status are/are not likely to be associated with children’s mental health and why. The research evidence suggests that children’s experiences of material deprivation may, for example, be more influential than measures of income poverty.

As in our Good Childhood Reports we should also move beyond a focus on mental health problems to consider measures of positive mental health, such as life satisfaction. This offers a less medicalised approach, which focuses on how children can flourish (rather than looking at their experiences as problems), and puts children’s own views and experiences at the forefront.