Why public policy for wellbeing needs more than one approach

This article is adapted from “Improving Interdisciplinary Research in wellbeing: A Review, With Further Comments, of Michael Bishop’s The Good Life: Unifying the Philosophy and Psychology of wellbeing”, in Journal of Happiness Studies. Read the full article here.

Wellbeing is what is ‘good for’ somebody. So surely it’s a good thing if people’s wellbeing increases? But this is a challenge for public policy because although we can objectively measure the number of people that define ‘good’ as say pleasure, or wealth, this won’t tell us what the good is in reality. Liberal democracies empower citizens to make such value judgements through the political process instead, notably through elections and participatory dialogues.

At the same time, there are better and worse theories of what leads to or drives wellbeing and these can be studied empirically. Psychologists, for example, often associate wellbeing with meaning in life and study it with psychometric surveys. Economists often associate wellbeing with the satisfaction of preferences and use income as a proxy to measure this in cost-benefit analysis. Policies should have a sound basis in such evidence.

Making wellbeing public policy

This means that wellbeing public policy has both democratic and technocratic elements – two modes that typically clash. How can these be balanced? And what methodology could the public policy process adopt to turn this tension into an asset rather than a threat?

In his recent book, “The Good Life: Unifying the Philosophy and Psychology of wellbeing”, Philosopher Michael Bishop proposes fostering collaboration across academic disciplines with differing views of wellbeing. His ‘inclusive approach’ has interesting lessons for wellbeing public policy.

Bishop notes that there is a long-standing incompatibility between what are otherwise very reasonable intuitions. For example, consider someone who is dying of a terminal disease at the end of a good life. They say they’ve had a good innings and are satisfied with their life. Some theorists argue that this subjective judgement is what matters for this person’s wellbeing. But they’re dying! Surely they are not well?

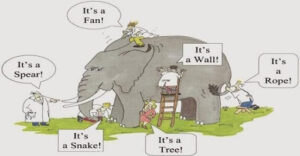

Bishop thinks that arguing over such intuitive judgements will never conclusively determine what is and is not wellbeing. A more practical approach is to be ‘inclusive’ and assume that everyone studying wellbeing is in fact studying the same phenomenon, just from a different perspective.

They are like the proverbial blind men and the elephant – each mistakes the part they feel for the nature of the whole creature. Let’s then set about analysing where perspectives overlap, where they clash, and in what ways they can be unified.

This ‘inclusive’ approach can be readily applied in contemporary wellbeing public policy efforts. Experts from many disciplines are often consulted regarding what wellbeing is and how it should be measured. Unhelpfully, the experts disagree. Adopting the inclusive approach in these debates could help experts to appreciate the unique perspective of each discipline.

A problem for the inclusive approach is that while it is reasonable it is not pragmatic. Wellbeing public policy needs some ways forward urgently.

Mid-level theories – a different approach to wellbeing policy

A parallel approach called ‘mid-level theories’ was recently proposed by Anna Alexandrova in her book ‘A Philosophy for the Science of wellbeing’. Alexandrova argues that a one-size-fits-all grand theory of wellbeing is not imminent, so taking an inclusive approach to finding one might be a waste of time. Instead we should develop many theories and metrics of wellbeing to suit specific policy areas. Mental health is a salient issue in social policy, for example, but less relevant to infrastructure spending, where wellbeing might pertain to sustainability.

An advantage of building mid-level theories is that by breaking wellbeing public policy up into chunks it becomes more manageable and democratisable. The development of wellbeing public policy does not need to be a top-down enterprise driven by government, academic experts, and national statistical agencies. It can be delegated to line areas to develop theories and metrics that suit their work.

These line areas can then use their service delivery arms to engage the public directly in participatory processes. In this way, the notion of wellbeing and how it is measured for wellbeing public policy can be democratised – a process that can be a source of wellbeing in its own right.

Wellbeing public policy has until now tried to achieve such democratisation through wide ranging consultations with citizens. In the UK, for example, the ONS held 175 events with around 7250 people as part of its National Debate on Measuring National Wellbeing.

While somewhat effective, this process is plagued by the same problems of clashing intuitive judgements and perspectives as academic debates. The size of these ventures also makes it difficult to distil nuanced theories of wellbeing for narrow but complex policy contexts like adult education, industrial strategy, or climate change policy.

The challenges for a bottom-up approach like mid-level theory building are scaling and generalising results for benchmarking and budgeting decisions. But when the top-down processes in wellbeing public policy are characterised by such deep disagreements a mid-level approach to policy is probably more pragmatic even if it is less exciting than a grand theory.