Bringing wellbeing evidence into the appraisal process

This practice example is part of our methods series and based on Tavistock Relationships’ new report ‘The Wellbeing Value of Reducing Parental Conflict: A cost-benefit analysis of Mentalization-Based Therapy for Parenting under Pressure‘.

In July of this year, HM Treasury published the UK’s first Green Book Supplementary guidance on Wellbeing Appraisal which sets out how the growing body of wellbeing evidence can be incorporated into the policy process. The guidance builds on decades of wellbeing science and reflects the new cross-government consensus on the WELLBY, a new unit value for wellbeing valuation.

We will be collating examples in which recommended wellbeing frameworks and evidence are used in real-life policy contexts. This new report is the first practice example of economic appraisal in which the WELLBY metric is used to capture the wider benefits of a parental conflict intervention. It makes the case for adopting a wellbeing framework to assess future interventions on family wellbeing and relationship support, whilst allowing for the comparison of spending proposals.

The evidence gap on relationships, parental conflict and family wellbeing

Between 2019 and 2021, Tavistock Relationships delivered a 10-week Mentalization-Based Therapy (MBT) intervention to support parents experiencing relationship difficulties and inter-parental conflict called Parenting Under Pressure. The programme was part of DWP’s Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) package of interventions across England that targeted parental relationships marked by sustained conflict. The MBT programme was evaluated in the Hertfordshire Contract Package Area, between July 2019 and May 2021, with data on 579 parents.

Partner relationships have long been recognised as one of the strongest drivers of adult subjective wellbeing. National data suggests that adults who are single, separated or divorced are at greater risk of loneliness, and there is a growing body of evidence that highlights the links between family wellbeing and individual wellbeing. Conflict between parents, whether together or separated, also has a significant negative impact on children’s mental health and their long-term life chances. Back in 2016, the Early Intervention Foundation identified the need to test interventions to see what worked to enhance inter-parental relationships and improve outcomes for children. Since then, they have appraised the available child and inter-parental measures and set up a hub for researchers and practitioners to access relevant evidence and tools.

Building a bespoke wellbeing framework

Tavistock Relationships’ report illustrates how a wellbeing lens can help identify and monetise social impacts that are traditionally more difficult to assess, in value-for-money terms. Wellbeing-informed Cost-Benefit Analyses (CBA) like this one can shed light on the social value of interventions and enable much-needed comparisons to the costs of programmes and policies. The research uses a bespoke wellbeing framework to identify the outcomes that matter most to wellbeing in the intervention’s Theory of Change model and to qualitatively describe MBT outcomes that cannot easily be monetised.

The evaluation scoping stage and the Theory of Change

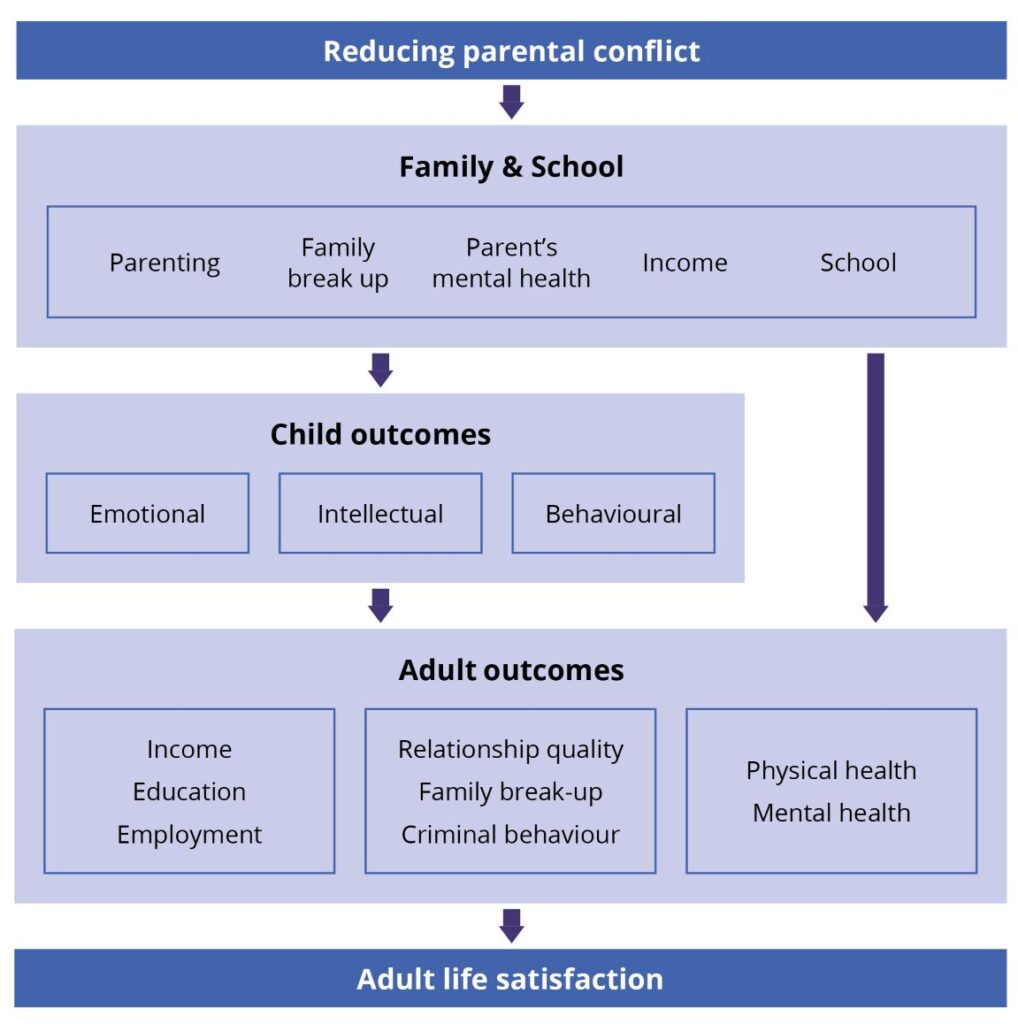

One of the first steps when incorporating wellbeing into the scoping stage of an evaluation is to map an intervention’s wellbeing aims and use estimates from robust published studies to value non-monetisable impacts [1]. The MBT programme uses evidence on relationship quality and mental health outcomes as a starting point to map the causal pathways that link reduced parental conflict to expected improvements in adult life satisfaction.

Table 1: ONS Measure of Life Satisfaction (source: Office for National Statistics)

These are presented in Tavistock Relationships’ adaptation of the Life Course model below (Figure 1) [2]:

Figure 1: Life course model of parental conflict and subjective wellbeing (Source: Tavistock Relationships)

Using wellbeing evidence to estimate impact and duration

The review of existing wellbeing evidence should be seen as an iterative process and much of our Centre’s work is aimed at improving the quality of evidence available for the primary domains of wellbeing, in line with the UK’s national measurement framework. Available research may not always be appropriate for the context in question and guidance published by Pro Bono Economics in collaboration with our Centre can help organisations assess the suitability of evidence to their contexts and understand the process of using available research. Some of the quality considerations for including evidence are: the source of variation in studies, the ‘other’ factors the estimated relationship is conditional on, the match with the target groups for the intervention and the age of the evidence.

Figure 2: Identifying and reviewing evidence as an iterative process (source: ProBono Economics)

As a before-and-after study, Tavistock Relationships’ research tracked measurable change in outcomes using two key psychological measures: Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE) to measure psychological distress, and the Couple Communication Questionnaire (CCQ) to measure levels of conflict between parents, levels of violent problem-solving and conflict in co-parenting the children.

Data from the report shows how at the start of the programme, 82 parents (32%) scored within clinical range of psychological distress. For 51 of these (62%) who completed post-intervention CORE, levels reduced to minimal/mild [3].

Mean pre-post intervention CCQ scores also showed statistically significant improvements in conflict between parents in both intact and separated relationships, and for violent problem-solving and for conflict about the children for all parent groups [4].

Our reviews of the wellbeing evaluation literature have shown that it is not always possible to build credible counterfactuals when assessing the effects of an intervention. As a programme grounded in the typical service conditions of couple and family therapy, building a control group or accounting for a ‘treatment as usual’ condition was not possible. This limitation in the study’s design is acknowledged and Tavistock Relationships uses secondary wellbeing evidence to describe the causal effects of MBT and estimate the duration of outcomes. Longitudinal outcomes data from RCTs and other studies, together with Tavistock Relationships’ clinical experience, are all used to estimate the long-term impacts of MBT in regards to the couple conflict, social functioning and depression. Uncertainty is addressed through sensitivity tests on assumptions that are made about the duration and attribution of changes [5].

Parental mental health: monetising wellbeing gains

The cost-benefit analysis framework used by Tavistock Relationships to estimate the value for money of the MBT programme includes the Treasury’s recommended metric, the WELLBY.

The Wellbeing-Adjusted Life Year (WELLBY) represents a one-point change for an individual on the ONS Life Satisfaction scale for one year.

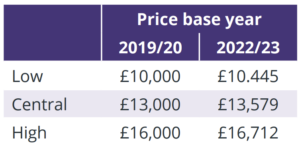

The programme’s CORE measure is used alongside the WELLBY value to monetise changes in the clinical levels of mental health for parents who took part in the programme. HM Treasury (2021) guidance uses research from our Centre to recommend a standard value of £13,000, ranging from £10,000-£16,000 per WELLBY.

Table 2: Monetary value of a WELLBY (source: Tavistock Relationships)

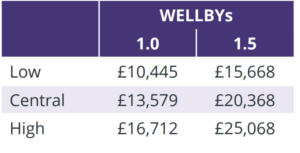

The work done by Layard et al. (2020) to appraise the Government’s lockdown measures is used to estimate the value of one year lived in a diagnosable state of mental illness in Quality-Adjusted Life-Years (QALY) which is estimated to reduce QALYs by 0.2 unit. If average life satisfaction in the UK is approximately 7.5, one year lived in depression roughly equates to a loss of 1.5 WELLBYs (= 0.2 QALYs x 7.5) [6]. Table 3 shows the monetary value of improvements in psychological distress among parents by the end of the programme in WELLBYs.

Table 3: Value in a reduction in clinical depression, for one parent, per year, 2022/2023 prices (source: Tavistock Relationships)

Based on completed post-intervention questionnaires by 258 parents and the assumption that each parent moving out of diagnosable depression has a wellbeing gain worth between £15,668 and £25,068 pa (Table 3), Tavistock Relationships estimate that the total monetary benefit associated with mental illness for 51-114 parents has a wellbeing value of £0.8m to £2.9 m per year (Table 4) [7].

Table 4: Wellbeing value of MBT per year, 2022/2023 prices (source: Tavistock Relationships)

Outcomes for children

The impact of the MBT programme on children was not included in the cost-benefit analysis as the wellbeing changes experienced by children could not be easily quantified. These were explored qualitatively at the end of the intervention when parents were asked whether their child’s wellbeing had increased, stayed the same or decreased. Just over half the parents sampled (53%) reported an improvement.

The potential impact of changes in children’s outcomes on the overall value of the intervention was obtained using an indicative “breakeven analysis” to estimate the required level of reduced mental health problems benefitting children to breakeven. Tavistock Relationships used Pro Bono Economics’ estimate of the average costs to the UK economy, associated with mental health difficulties, of £260,000 over a child’s lifetime.

Although the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has specific measures for children’s wellbeing (aged 0-15 years) and young people’s wellbeing (aged 16-24), there is still a lack of consensus on the monetary value of the life satisfaction of children. The Good Childhood report 2021 recognises the potential for using the WELLBY to inform spending decisions in Children and Young People’s social policy whilst pointing to the lack of evidence to allow us to do this.

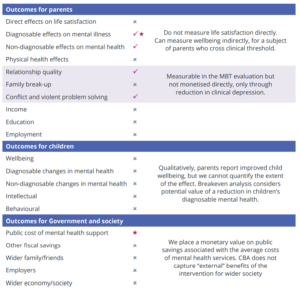

Table 5: Items that can be quantified (tick) and monetised (star) (source: Tavistock Relationships)

The value of applying wellbeing guidance

The wellbeing valuation framework used by Tavistock Relationships illustrates both the benefits and challenges of incorporating wellbeing into economic appraisal. Their research makes wide use of existing HMT guidance and wellbeing evidence, recognising that Tavistock Relationships’ cost-benefit analysis represents an initial approximation of the MBT programme’s wellbeing value. The Life Satisfaction metric has now been added to the organisation’s package of pre-post measures for the Reducing Parental Conflict programme, providing scope for improving appraisal in the future. As such, it marks an important step to improve the quality of evidence on relationship quality and family wellbeing that is used to inform spending decisions

Explore this area further

See our children and young people ONS4 evaluations

Read our methods series papers