Briefing: Neighbourhood influence on culture, arts and community engagement

Downloads

The big picture

Arts, cultural and community engagement positively influences our wellbeing in multiple ways. Participating in these activities can improve life satisfaction, mental health functioning and physical health.

Researchers have found that the positive relationship between arts, cultural or heritage attendance and wellbeing exists regardless of where people live.

However, people living in hard-pressed communities, deprived and multicultural areas are less likely to engage than those living in wealthier, cosmopolitan or countryside areas, and this is after factoring in individual characteristics like age, gender, ethnicity, partnership status, educational level, socio-economic status, monthly income, etc.

It is possible that in deprived areas, lower engagement is a result of a combination of factors such as:

- Less availability of or accessibility to arts and cultural offerings (opportunity)

- Less affordable options for people living in those areas (capability)

- Specific social norms of people living in these areas (motivation) (1)

Types of community engagement

Arts engagement = actively performing or taking part in the arts (e.g. music/dance/theatre), visual arts, and crafts (e.g. drawing/woodwork/painting/photography/ceramics/sculpture/textiles). Includes being a member of book clubs or writing groups, reading books, writing short stories/poems.

Cultural and heritage = attending or visiting museums, galleries or exhibitions; the theatre, or concerts; the cinema; festivals, fairs and events; stately homes or buildings; historical sites; landscapes of significance; libraries and archives.

Sports and physical activities = participating in exercise classes; being a member of sports clubs; doing yoga/Pilates, running/jogging, swimming/diving, martial arts, team sports, skiing, golf, horse riding, water sports, racquet sports, rambling/walking, cycling, going to the gym.

Volunteering/community groups = charitable volunteering, conservation volunteering or school or community volunteering. Includes being part of a community group that meets frequently. Also engaging with education or evening classes; political parties, trade unions; environmental groups; or tenant, resident or neighbourhood watch groups; and social clubs.

How our mental health and wellbeing benefit from community engagement

Previous studies have shown that arts participation, cultural attendance and visiting museums and heritage sites can all lead to positive psychological, physiological, social and behavioural responses. The evidence indicates that participating in arts and cultural activities generally has

a positive effect on our health and wellbeing. (2) Different types of community engagement have been found to be associated with different wellbeing benefits.

| Life satisfaction | Mental distress | Functioning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arts engagement (read more) | Participation in arts activities more than once per week was longitudinally associated with higher life satisfaction. (3) | Participation in arts activities more than once per week was longitudinally associated with lower levels of mental distress. (3) | Participation in arts activities more than once per week was longitudinally associated with better mental functioning in general. (3) Weekly engagement in literature activities was associated with greater levels of physical functioning. (4) |

| Cultural engagement/heritage (read more) | Cultural attendance at least once/twice per year was associated with greater levels of life satisfaction. (3)

Visiting museums and heritage was also longitudinally associated with greater levels of life satisfaction. (5) |

Weekly cultural attendance was associated with lower levels of mental distress. (3)

Visiting museums and heritage was also longitudinally associated with lower levels of mental distress. (5) |

In further studies, cultural and heritage activities were also associated with better mental functioning in general. (5)

Engaging in cultural and heritage activities several times a year was associated with better social and physical functioning and general health. (4) |

| Physical activities and sports (read more) | Not addressed in this study. | Not addressed in this study. | Associated with greater levels of physical functioning, general health, and vitality when engaged in 1-3 days a week. |

| Volunteering/community groups (read more) | Not addressed in this study. | Associated with reduced levels of mental distress in older generations (Baby Boomers) but not in younger generations. (6) | Volunteering and community groups were associated with greater vitality for those who engage monthly or weekly. (4) |

Table 1. Types of community engagement and wellbeing benefits.

Moreover, the benefits of arts participation and cultural engagement on mental distress and life satisfaction hold after controlling for variables like gender, demographic background, socio-economic characteristics, health behaviour and support from family and friends. This analysis also showed that the wellbeing benefits of arts and cultural engagement were not explained by factors such as personality, previous arts engagement, and previous mental health. However, the direction of the relationship cannot be confirmed. (3)

Similarly, the benefits of volunteering are independent of demographic characteristics (e.g. age, partnership status, long-standing impairment) and socio-economic position (e.g. education, employment status, monthly income). However, there was a cohort effect which suggests that these benefits are greater for people from older generations than for younger birth cohorts. This suggests that there might be changing social attitudes in how volunteering is portrayed, e.g. as a means to collectively improve society vs a strategy to promote individuals’ health and wellbeing, which could play a role in whether the experience of volunteering is beneficial for wellbeing. (6)

Life satisfaction was measured with a seven-point scale (1: completely unsatisfied to 7: completely satisfied).

Mental distress was measured using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12).

Functioning was measured using the 12-item or 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12 or SF-36) and it was used as a proxy for measuring health-related quality of life. We used 8 of the indicators including: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems and mental health.

Wellbeing benefits are independent of regional location (5)

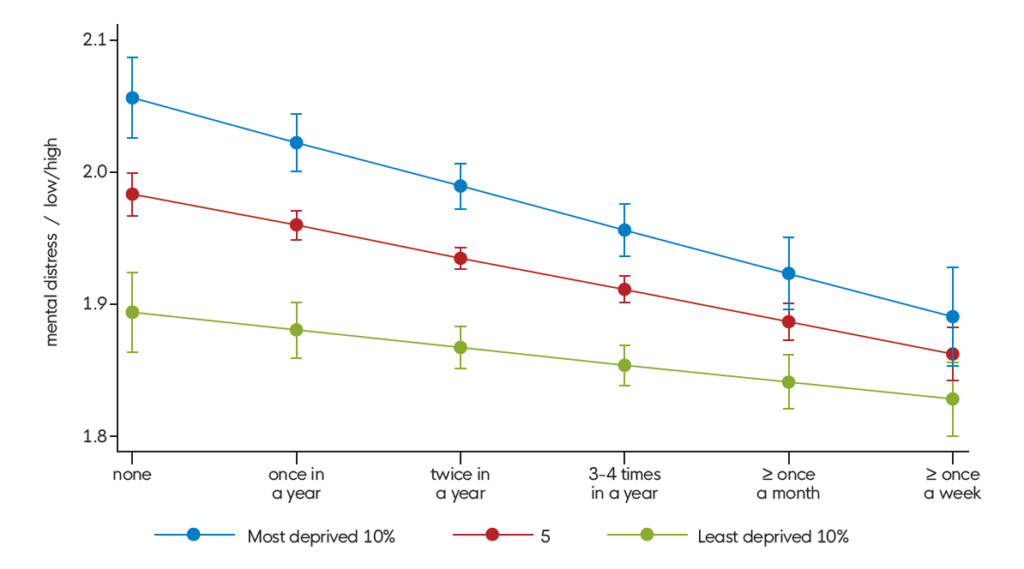

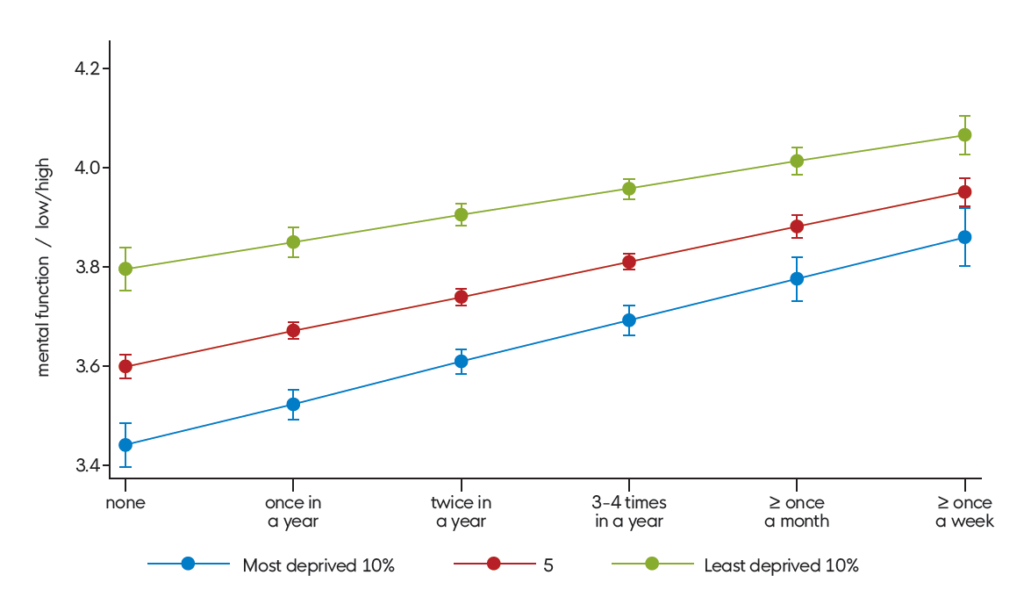

Individuals living in areas of high deprivation are at greater risk of poorer mental health, therefore researchers examined the extent to which such individuals benefited from engagement compared to those living in wealthier areas.

There is a positive relationship between cultural and heritage attendance and wellbeing that is independent of individuals’ regional locations or area deprivation. While the effects are small, it is significant that both cultural and heritage attendance are constantly associated with better wellbeing regardless of where people live. The benefits of participation can be observed even amongst those living in deprived areas. Note that this analysis did not include performing arts.

That said, some small moderation effect was found between cultural engagement and area deprivation, whereby the wellbeing benefits of cultural engagement may be greater for those living in deprived areas. As people engage more frequently, mental distress decreases and mental health functioning increases more notably for those living in the most deprived areas. Moreover, as the frequency of engagement increases, the mental health gap between least and most deprived areas narrows (Figures 1 and 2). Life satisfaction benefits do not seem to be moderated by area deprivation.

The benefits of volunteering on mental distress and mental health functioning were also found across neighbourhoods, regardless of where people live. (6)

Figure 1. Association between cultural attendance and mental distress by levels of area deprivation.

Figure 2. Association between cultural attendance and mental health functioning by levels of area deprivation.

Engagement levels vary geographically (7)

While the public, social prescribers and healthcare professionals are increasingly aware of the benefits of participating in arts and cultural activities, engagement in these activities is still unequal. Research has focused on individual-level characteristics to explain the uneven patterns of engagement. For instance, women, individuals from ethnic majorities, people with higher monetary resources and specific acquired tastes are said to be more likely to engage in the arts.

Researchers wanted to find out if engagement behaviours could be explained by geographic factors (our residential location), in addition to individual characteristics. Four geographic variables were examined:

- Level of urbanisation (rural/urban)

- England Region (North/Midlands/South)

- Index of Multiple Deprivation

- Geodemographic Output Area Classification (cosmopolitan student neighbourhood/countryside/ethnically diverse professionals/hard pressed/inner city cosmopolitan/multicultural/suburban/industrious communities)

In particular, there was more evidence for differences in participation based on level of area deprivation. For example, in England:

- People living in countryside areas are more likely to participate in arts compared to those in industrious communities.

- People living in hard-pressed communities and multicultural living areas engage less in cultural activities, whereas people living in wealthier areas, affluent countryside and cosmopolitan areas were much more likely to engage in cultural activities.

- Those living in the 10% most deprived areas are significantly less likely to engage in cultural activities.

Where we live is important but does not always determine whether we engage. For example, it was found that people living in deprived neighbourhoods but with high socio-economic status still engaged in cultural activities (the same was not found for arts participation). However, it remains to be explored whether they engaged in the areas they lived or somewhere else.

Overall, arts and cultural access or participation rates vary depending on geographical factors such as the spatial setting where we live and the characteristics of our neighbourhood, and this holds true regardless of variation in individual variables like age and gender.

People in depraved areas engage less, regardless of their socioeconomic status (8)

We know that where individuals live can be strongly correlated with their own socioeconomic status, so researchers compared levels of engagement using propensity score matching to account only for the effect of place rather than socioeconomic position. They compared participants living in the 20% most deprived neighbourhoods with those living in the 20% least deprived neighbourhoods.

Propensity Score Matching was done by pairing the characteristics of people in the most deprived areas with those of the people in the least deprived areas so that any differences observed are explained by the level of area deprivation only and not by individual characteristics such as age, gender, ethnicity, whether respondents were living alone, marital status, whether respondents had children under 16 in the household, educational levels, occupational status, annual personal gross income, and housing tenure.

The results showed that, effectively, people living in the most deprived places are less likely to engage than those living in the least deprived places, independent of individuals’ demographic background, socioeconomic status or regional location. And it applies to all three types of activities (arts participation, cultural attendance, museums and heritage sites):

| Arts participation:

ATT = -0.38 |

Cultural attendance:

ATT = -0.37 |

Museums and heritage sites:

ATT = -0.41 |

|---|

Source: UKHLS 2010/12. ATT=average treatment (deprivation level) effect.

Results held when comparing the 10% most deprived vs 10% least deprived, and even when comparing the 20% most deprived areas with those in the 40% medium-deprived areas.

The level of deprivation was defined using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), comprising 7 domains of deprivation: income, employment, education, skills and training, health and disability, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment. Similar results were obtained across all 7 domains, suggesting that all these neighbourhood characteristics are associated with less engagement.

Possible reasons for low engagement in deprived areas (3, 8)

These geographical differences in engagement behaviour could be explained by:

- Area characteristics (contextual effect): varying number of arts venues, arts programmes, heritage sites and accessibility characteristics, such as unsafe streets or poor transportation, may predispose more deprived communities to lower participation. In other words, the neighbourhood infrastructure and design could be influencing people’s behaviours. Characteristics like accessibility (e.g. transportation), attractiveness (e.g. green space and parks), community design features (e.g. street connectivity), public resources and services (e.g. facilities, arts venues and recreational amenities) as well as safety and stability—which deprived areas usually lack— might affect patterns of participation. Also, there may simply be fewer cultural assets available in these spaces or these might be neglected or unadvertised. In sum, these factors may exacerbate social and health inequalities.

- Personal characteristics (compositional effect): people tend to cluster together according to their demographics, socioeconomic position and lifestyle or cultural preferences. Therefore areas may vary by population composition which in turn influences engagement patterns. There might be unobserved or unquantifiable individual personal characteristics preventing engagement, such as cultural norms, values, or childhood experiences. In turn, socially-constructed norms, values and attitudes towards arts and culture may be reinforced by collective behaviours, exacerbating cultural divides across places. Indeed, ‘social contagion’ is a process whereby behaviours, attitudes and even awareness of the cultural offer may be influenced by our peers living in the same neighbourhood. Social networking and communications can also influence individual behaviour. Therefore, there might be a cultural opportunity and capability to access (infrastructure) but no motivation or awareness to participate.

Implications for policy and practice

- Increasing arts and cultural engagement could play an important role in improving wellbeing at a population level.

- Given the health benefits of arts and cultural engagement, it is reasonable to assume that expanding access to these programmes, especially in deprived areas, may help to reduce health and wellbeing inequalities, in line with the Government’s “Levelling Up” programme. However, we do need to actually test if improving access/availability will help or if it is actually cultural norms that matter.

- Referral processes for arts and cultural engagement should take into account individual-level characteristics and geographical contexts. There is probably great potential for social prescribing schemes in highly deprived areas, where arts and cultural resources and services might be more scarce.

- Since investment in cultural assets in different locations holds equal potential for positively influencing health and wellbeing, more central arts and cultural funding may be needed in more deprived areas where they tend to face greater difficulty in obtaining income from local councils.

- Types of arts and cultural activities and frequency of engagement can have differential associations with health amongst middle-aged adults, which may be helpful when planning the ‘dosage’ of public health initiatives.

- Given the positive health impact of volunteering in older generations, volunteer work can be promoted among older adults and thus help the UK population to age more healthily. See, for instance, the volunteering strategies of the Centre for Ageing Better.

- The results suggest that place-based funding schemes that focus on areas of higher deprivation and that increase individual motivation and capacity to engage in arts and cultural activities should be explored further to see if they can help promote better wellbeing among residents.

- However, the analysis was unable to distinguish people who lacked opportunities to engage from those who were disinterested in engaging, which may have different implications.

Social prescribing

Social prescribing is a way to connect people to social, emotional and practical support in their communities and beyond, usually through referrals from health and social care.

The benefits of taking part in arts and cultural activities in community settings are clear, but too many people are still missing out, especially in deprived communities. It’s not enough for these activities to exist; people need to be supported to take part.

Social prescribing can help connect people to these local activities by emphasising their wellbeing benefits, and by supporting people – for example through buddying schemes – to attend for the first time. Removing barriers to engagement can benefit not just individuals with low wellbeing, but the wider community – as the mental health inequality gap narrows.

The wellbeing benefits of volunteering are also key, as volunteering can provide a gateway to wider community participation. Referrals to volunteering are increasingly an important part of social prescribing.

This evidence rightly highlights the difference between people lacking opportunities, and people being disinterested in taking part. Social prescribing puts a person’s context, motivations, and aspirations at the heart of personal plans, and can therefore provide tailored referrals to local activities.

– Ingrid Abreu Scherer, Head of Accelerating Innovation at National Academy for Social Prescribing

Data and methods

This briefing summarises the findings of WELLbeing & COMMunity Engagement (WELLCOMM), an ESRC-funded project led by researchers at University College London in collaboration with the What Works Centre for Wellbeing [ES/T006994/1].

Methodologies, data sources and paper citations are detailed below.

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M.M. & West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Sci 6, 42 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- Fancourt D, Finn S. (2019) What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Wang, S., Mak, H. W., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Arts, mental distress, mental health functioning & life satisfaction: fixed-effects analyses of a nationally-representative panel study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 208.Data: UKHLS Waves 2(2010-12) and 5 (2013-15)

Sample: 23,660 individuals (average age=47)

Analysis: Longitudinal analysis, fixed effects models.

Engagement measure: Respondents were asked how often in the last 12 months they had done arts activities/ attended cultural events. A list of the activities and events is provided in the research paper. - Elsden, E., Bu, F., Fancourt, D. & Mak, H.W. (under review). Frequency of leisure activity engagement and health functioning using SF-36 over a 4-year period: a population-based study amongst middle-aged adults.Data: British Cohort Study 1970 Wave 9 at age 42 (2012) and Wave 10 at age 46 (2016)

Sample: 5,799 adults

Analysis: Cross-sectional study; OLS & logistic regressions

Engagement measure: The questionnaire contained 26 leisure items from 5 broad activities: physical activity, cultural engagement, arts participation, volunteering/community groups, and literature activities. Participants were asked about their frequency of engagement in each leisure item. - Mak, H.W., Coulter, R. & Fancourt, D. (2021a). Associations between community cultural engagement and life satisfaction, mental distress and mental health functioning using data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS): are associations moderated by area deprivation? BMJ Open.Data: UKHLS Waves 2 (2010-12) & 5 (2013/15)

Sample: UKHLS=14,783 (average age=47)

Analysis: Cross-sectional study; OLS regressions with interaction terms; matching participating household’s addresses to the ONS Postcodes Directory.

Engagement measure: Respondents were asked how often they had attended any of the cultural events, visited museums/galleries and visited heritage sites in the past 12 months. - Mak, H.W., Coulter, R., & Fancourt, D. (2022). Relationships between volunteering, neighbourhood deprivation and mental wellbeing across four British birth cohorts: Evidence from 10 years of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Data: UKHLS waves 2 (2010/12), 4 (2012/14), 6 (2014/16), 8 (2016/18), and 10 (2018/20).

Sample: 10,989 participants

Analysis: Longitudinal study; fixed effects regressions; matching participating household’s addresses to the ONS Postcodes Directory.

Engagement measure: Respondents were asked how often they had given any unpaid help or worked as a volunteer for any type of local, national or international organisation or charity in the last 12 months. - Mak, H. W., Coulter, R., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Do arts and cultural engagement vary geographically? Evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. Public Health, 185, 119–126.Data: UKHLS Wave 2 (2010/12)

Sample: 26,215 (average age=48)

Analysis: Cross-sectional study; binary and ordinal logistic regression models with interaction terms; matching participating household’s addresses to the ONS Postcodes Directory.

Engagement measure: Respondents were asked whether or not they had engaged in a series of arts/cultural activities in the past 12 months. - Mak, H.W., Coulter, R. & Fancourt, D. (2021b) Associations between neighbourhood deprivation and engagement in arts, culture and heritage: evidence from two nationally-representative samples. BMC Public Health.Data: UKHLS wave 2010-12, and Taking Part Survey wave 2010/11

Sample: UKHLS=14,782 (average age=47) & TP=4,575 (average age=48)

Analysis: Cross-sectional study, propensity score matching; matching participating household’s addresses to the

ONS Postcodes Directory.

Engagement measure: Respondents were asked how often they had done particular activities, attended any cultural events or visited museums and heritage sites in the last 12 months.

- The big picture

- Types of community engagement

- How our mental health and wellbeing benefit from community engagement

- Wellbeing benefits are independent of regional location (5)

- Engagement levels vary geographically (7)

- People in depraved areas engage less, regardless of their socioeconomic status (8)

- Possible reasons for low engagement in deprived areas (3, 8)

- Implications for policy and practice

- Social prescribing

- Data and methods

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]