Do you really care about your staff’s happiness?

How organisations balance wellbeing and performance during a crisis

Case study evidence: the quick read

We looked at five organisations to understand how actions taken during the COVID-19 pandemic aligned with their values and priorities about staff wellbeing. We found that:

- Organisations that had a strong interest in staff wellbeing prior to lockdown were more likely to respond proactively to the crisis.

- Organisations at the early stages of putting in place a wellbeing strategy had more reactive responses and were more likely to be viewed as inauthentic in their concern for staff.

- Messages of care and concern were more likely to be viewed as authentic where there were:

- strong foundations of mutual support between leaders and staff;

- existing wellbeing services (e.g. wellbeing champions, mental health aiders).

- Corporate messaging about care and concern for employees’ wellbeing in times of crisis is not sufficient in itself be regarded as authentic. It needs to be followed by tangible, continuous and consistent efforts.

The COVID-19 shock, in particular, threatened both performance and employee health and wellbeing. The pandemic elevated workforce health as a priority in an unprecedented way, but in a context of great economic uncertainty, making it difficult for organisations to predict whether their responses would be effective.

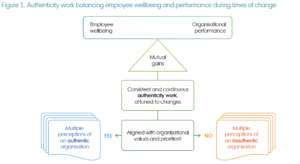

It is possible for an organisation to support both staff wellbeing and organisational performance at the same time. We call this mutual gains.

The principle of mutual gains refers to how employers maintain a balance of activities to address organisational priorities for performance and employee concerns, for example around health and wellbeing. Sometimes these can be the same, other times they differ. For example, where employers benefit from having a capable, flexible and committed workforce, their employees can cherish an inclusive culture, a sense of community and a positive work environment in which they can personally and professionally grow.

During a crisis, mutual gains are more likely to be achieved if the organisation implements visible ongoing and consistent actions that are aligned to its values and priorities. We call this authenticity work.

An organisation perceived to be authentic in its concern for employees’ health and wellbeing is likely to benefit from positive and trusting relationships with employees. However, the reverse is true if an organisation communicates a concern for employee health and wellbeing, but then acts in a way that is detrimental to health and wellbeing. Authenticity work takes effort but enables organisations to adapt to change and to the shifts in concerns of different stakeholders so that values and actions are aligned.

We asked different firms what steps they took to engage in authenticity work when responding to the economic and wellbeing threats of the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. The Foundation

Initial authenticity work was closely related to the level of wellbeing focus prior to lockdown.

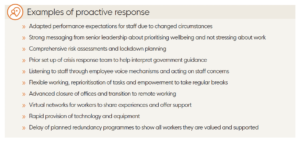

Unsurprisingly, organisations with a more comprehensive and advanced wellbeing approach before the pandemic were more likely to take a proactive response in protecting their staff. Early proactivity, in turn, was more likely to be seen as authentic.

The type of wellbeing and performance orientation pre-COVID is an indication of the organisation’s existing capability to immediately respond to the shock. An organisation with advanced foundations is one with an established approach to balancing wellbeing and productivity; employers and employees are able to gain in a variety of ways. Organisations like these are likely to have more proactive first responses to the shock:

Q&A

- Are screen-based jobs more likely to respond proactively than those sectors requiring people to be physically present? Not necessarily. A construction firm, for example, deployed a strong proactive response despite requiring people to be on site and operating within a complex network of contracted relationships and client expectations.

- Small organisations don’t usually have the resources to plan. Aren’t they fated to be reactive? No, we found small firms that responded proactively. For example, a small tech company moved to remote working prior to the government mandate to suspend all business activity on sites. It was certainly easier to do so due to the remote working set up for the majority of business operations, but the pre-existing wellbeing structures helped the process.

2. The Message

Organisational features and specific communication techniques helped to get wellbeing messages across more genuinely.

Shortly after the lockdown, organisations started communicating messages of care and concern for their staff. Managers and leaders from organisations with mature wellbeing strategies were thinking of and living by their messaging when attempting to relay the following:

- acknowledging the difficulties of working during a pandemic;

- adjusting performance expectations, recognising that people were facing many different demands such as home schooling;

- committing to support workers’ physical, mental, social wellbeing and financial security.

Q&A

- Can an organisation that’s never expressed concern about staff seem authentic about it in a crisis? You have to start from somewhere. Our case studies suggest that you can change perceptions of authenticity if organisational actions that would follow communication at any point in time were aligned with the main message.

- Many organisations were only just starting to develop a wellbeing strategy when hit by COVID-19. Were they able to communicate authentic messages of care and concern at all? We didn’t find this to be the case, but it is possible if efforts were made to communicate their concern effectively and take sensible action. Authenticity is out being consistent, so you may need to be patient.

3. The Actions

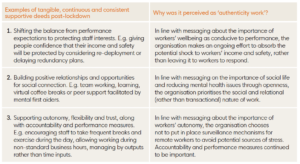

Messages of care must be followed by tangible and continuous supportive efforts post-lockdown to be seen as authentic.

As in normal times, in a crisis, organisations’ messages of care and concern about staff were more likely to be seen as authentic if they also took tangible and consistent action to support staff wellbeing.

This is about taking regular time to check whether we are doing what we said we would and meeting our intentions to support our employees’ wellbeing, while recognising that their interests and concerns can change. The table below shows examples of what organisations did and how these actions were received within the organisations:

Q&A

- Could we regard organisations that were unable to retain employees as not engaging in authenticity work? Indeed, we saw that organisations did have capability to retain their employees in the initial aftermath of the crisis, but some of them made use of the furlough scheme as the pandemic progressed. The key was to maintain an ongoing, honest and transparent dialogue with employees, informing them of the financial viability and involving them in the efforts to retain staff where possible.

- What about organisations that are just starting up and cannot afford to allow people to work non-standard business hours? It is possible to support authenticity work by having continuous conversations with people and keep identifying their interests and concerns. If it is not possible to accompany people’s preferences at a particular time we can still acknowledge their goals and interests and explain openly the company’s efforts to meet these.

Implications for employers, HR people and wellbeing leads

Focus on dynamic, continuous and consistent actions and adapt to changes in employees’ interests and concerns;

that is, focus on ‘authenticity work’.

- Where there are no positive employment relations, mutual respect and trust, authenticity work will be more difficult to attain during the first stages of a crisis. However, adverse initial contexts can be overcome in time, establishing these conditions gradually. You have to start somewhere and it’s better late than never, considering that organisations have to adapt to a range of external factors, such as changes in technologies, legislation and major organisational changes.

- Some could say it is obvious that organisations that were doing better before the pandemic will do better after. However, this also indicates that a health and wellbeing focus can create resilience so it should be a priority to establish. Consistent action now may lead to successfully secure mutual economic and wellbeing gains in the future.

- To demonstrate that your concerns have shifted to attaining performance and worker wellbeing, make sure to keep implementing tangible actions and processes beyond the immediate responses to the crisis. This will pick up on people’s changing interests and needs as their circumstances change.

Methods

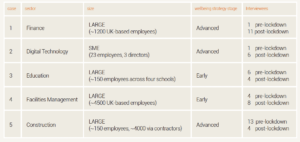

Multiple longitudinal case study with qualitative data collection.

Researchers from Employment Systems and Institutions Group, Norwich Business School, University of East Anglia, conducted fieldwork with five organisations as part of a research programme supported by the Economic and Social Research Council.

Five case studies were built based on qualitative data collected pre- and post- lockdown. This included:

- remote semi-structured interviews with employees at different levels (i.e. leaders, wellbeing practitioners and workers);

- supplementary company documentation;

- a survey of initial COVID-19 responses by organisational decision-makers.

The case studies were recruited via a call for interest using a purposive sampling strategy. The final sample comprised a total of 25 pre-lockdown and 33 post-lockdown interviewees, with data collection spanning December 2019 to November 2020. Organisations were picked to represent differing sizes, sectors, and different stages of putting inplace joint wellbeing and performance initiatives.

Interview guides and analysis themes focused on:

- Current organisational status and perceptions of wellbeing and performance balance

- Internal and external factors that led to establishing wellbeing and performance structures

- How the structures and interventions were put into place and experienced by employees

- Responses surrounding external shocks and shifts in employment relationships

The study was designed on the assumption that organisations are fluid and adaptable to a changing context. Thus, while the outbreak of COVID-19 was an exceptional case of external shock that happened in the middle of fieldwork, research questions and methods did not require considerable modification between pre- and post-lockdown stages.

All data collection received ethical approval through the University of East Anglia’s research ethics processes and the data collection is GDPR compliant.

Downloads

You may also wish to read the blog article on this document.

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]