How has Covid-19 affected loneliness?

Downloads

Headlines

- People who felt most lonely prior to Covid in the UK now have even higher levels of loneliness. This increase began as physical distancing and lockdown measures were introduced in the UK, in March 2020.

- Adults most at risk of being lonely, and increasingly so over this period, have one or more of the following characteristics: they are young, living alone, on low incomes, out of work and, or with a mental health condition.

- The impact on wellbeing from people at risk of loneliness is likely to be compounded by other economic and social impacts experienced by the same people, such as those experiencing job losses and health anxieties.

What do we mean by 'loneliness'?

Loneliness is a feeling that the quantity and quality of our relationships are not as good as we would like them to be. This is different from being isolated or alone, which are more objective measures of how much time we spend with how many other people, or solitude, which can in fact be positive and restorative for wellbeing.

Loneliness can be social, where we feel a lack of social connections, emotional, where we feel like we lack meaningful relationships to the extent that we don’t belong, and/or existential, where we might feel entirely

separate from other people

Background

Before Covid-19 reached the UK, loneliness had already been recognised as an important issue facing many people in society. Social connections and having someone to rely on in times of trouble is one of the strongest drivers of overall wellbeing. Feeling lonely is strongly associated with reporting high anxiety and has been linked directly to poor physical and mental health.

The government appointed a Minister for loneliness in 2018, followed by the first Loneliness strategy later

that year, which included commitments to act to reduce chronic loneliness, and recommendations on standardising measures for loneliness, building on our review of the evidence base around loneliness.

The January 2020 progress report identified that somewhere between 6% and 18% of the UK population often feel lonely and highlighted the importance of a whole society approach to tackling loneliness, working across government and in partnership with other sectors.

On March 23rd 2020, The UK Prime Minister addressed the nation to effectively put the UK into ‘lockdown’, prohibiting people from leaving home without a reasonable excuse and banning public gatherings.

Social distancing guidance applied to everyone. In order to reduce the spread of the virus, people were told to avoid close physical contact with anyone they did not live with. People with suspected symptoms were

told to ‘self isolate’, and people at severe risk of the virus to ‘shield’, staying at home as much as possible and not coming into contact with anyone.

At the same time, non-essential shops, pubs and restaurants, community venues and theatres were all closed. Sporting and music events were cancelled, and most aspects of social life put on hold. This has had a profound effect on our relationships and communities and how we engage with other people.

By July 2020, lockdown has been eased, and under new guidance governing our interactions and movement, some people have been able to return to their workplaces and schools, visit family and friends and return to shops, pubs and sports.

Our means of socialising and communicating with others continues to evolve, but remains very different to before March 2020. Data collected by the Covid Social Study from over 70,000 people has shown how loneliness has been affected between March and July 2020.

It provides insights into how many people have been lonely during this uncertain time and what the risk factors are that policy makers and practitioners should recognise in their efforts to alleviate loneliness. This briefing summarises the findings from this study.

Prior to Covid-19, the Understanding Society (USoc) Survey found that 8.5% of people in the UK answered that they were often or always lonely. Covid Social Study data found that data collected between 21st March and 10th May, this was 18.5%.

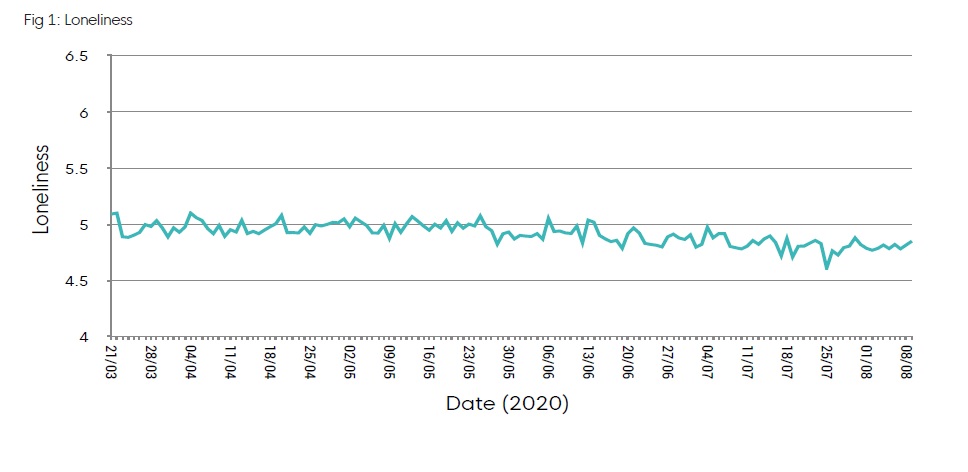

The average score for adults on the UCLA scale was 5 during the most stringent period of lockdown. This

compares to an average of 4.3 from the UKHLS data. Between March and July, the UCLA score has fallen

slightly, with people feeling less lonely in the period since measures were eased, however this has not yet fallen to pre-Covid levels.

Who is lonely?

How to measure loneliness

The Covid Social Survey used the UCLA 3-item loneliness scale, which asked people to answer on a 3 point scale from ‘hardly ever/never’ to ‘often’:

- How often do you feel that you lack companionship?

- How often do you feel left out?

- How often do you feel isolated from others?

The lowest possible combined score on the loneliness scale is 3 (indicating less frequent loneliness) and the highest is 9 (indicating more frequent loneliness). There is no standard accepted score for which a person would definitely be considered lonely.

The survey also asked the single item direct question “How often do you feel lonely”, using the same 3 point response scale.

This average of course hides significant variation between individuals and groups. Analysis of the data4 identified the characteristics of people at higher risk of loneliness. Important risk factors for adult loneliness are:

- Being young (18-30)

- Living alone

- Having low income

- Being unemployed

- Having a mental health condition

Other characteristics carry a small increase in the risk of being lonely, both before and during the pandemic.

- Non-white ethnicity

- Low educational attainment

- Being female

- Living in urban areas.

The Covid-19 effect

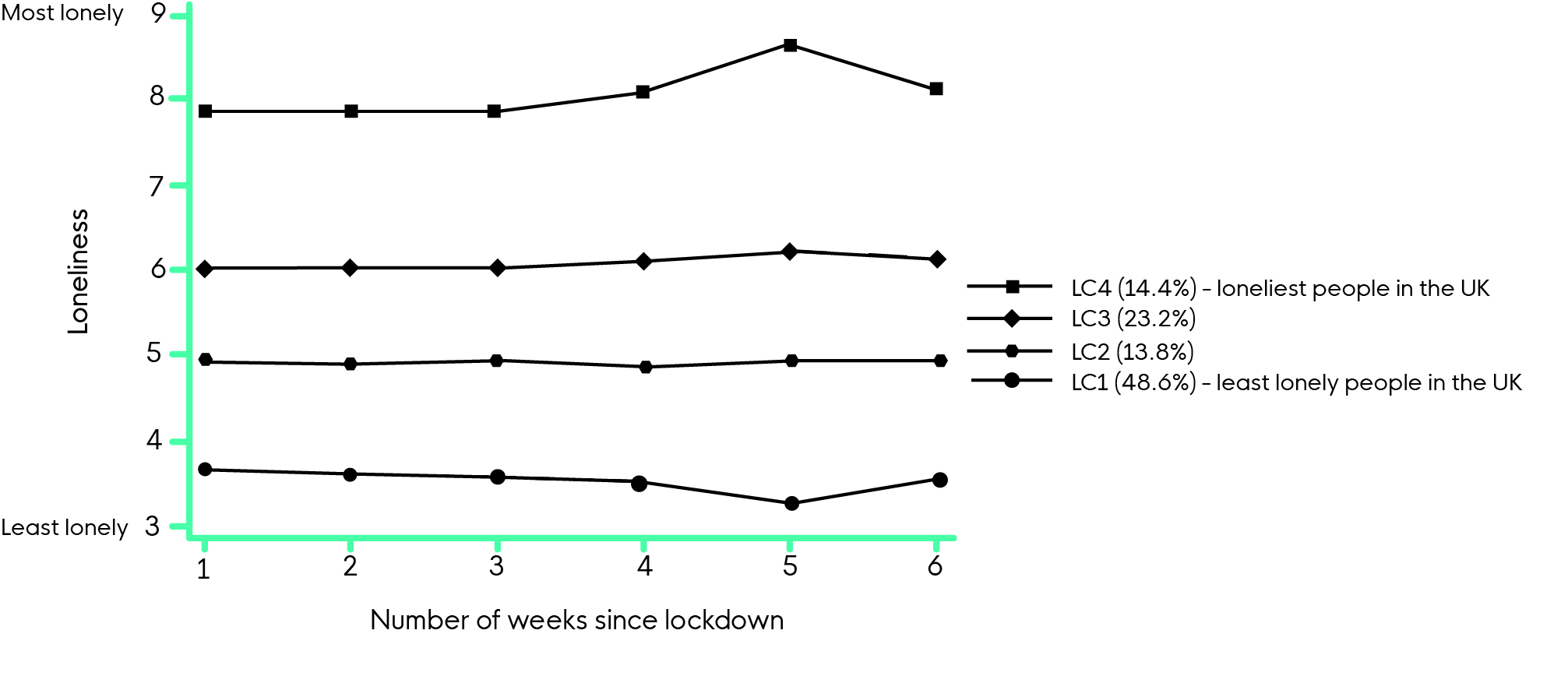

Young adults (aged 18-30), people with low household income and those living alone were at heightened risk of loneliness during the pandemic. Since March, being a student is a higher risk factor than usual. The loneliest have become lonelier – In the first six weeks of lockdown, loneliness levels increased in the highest loneliness group.

This group is made up of 14% of the population, who scored an average of 8- 8.5 over this period on the UCLA 9 point scale. The least lonely have become even less lonely. This group is made up of 49% of the population. Living with others or in a rural area, and having more close friends or greater social support were protective.

Fig 2 Estimated growth trajectory for each class latent class based on the 4-class unconditional GMM with free time scores.

Implications for a wellbeing-based recovery

The evidence finds that many people that are most at risk of feeling lonely, will have felt increasingly lonely during these times of social distancing and isolation, heightening the importance of addressing loneliness for people in the UK.

Increased loneliness for some people is particularly concerning because the risk factors of loneliness are common to other important wellbeing risks. As such, increased loneliness is likely to compound other impacts on our wellbeing from the health, economic and social changes that people have experienced.

For example, loneliness will compound the health impacts for people with a mental health diagnosis, or the economic impacts for those out of work or on low incomes. This evidence provides insights into who is most at risk of feeling lonely, which can be used by policy makers and practitioners to target interventions appropriately.

Whilst the majority of risk factors remain unchanged since before Covid, increased attention should be paid to young people, those living alone, on low incomes and students, who have been at an even greater risk of loneliness over this period.

Alleviating loneliness has been shown to work through:

- well tailored interventions, that take into account things like access to technology,

people’s interests and where they live - reducing the stigma of loneliness

- supporting relationships can be important.

However, more evidence of the effectiveness of different interventions particularly for younger age groups is required, whilst also addressing the underlying drivers of loneliness. For example, the Covid Social Study data found that over the past few months, none of the protective social factors such as having better social support moderated the relationship between mental illness and loneliness as we might have expected, which may have been due to the difference in how people have experienced social support during

lockdown, with more virtual and less physical interactions.

Downloads

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]