Synthesising Spirit of 2012 project case studies

Downloads

The quick read

We looked at case studies from ten Spirit of 2012 funded projects to find ‘how’ and ‘why’ creative activities can improve wellbeing.

We found:

- All projects reported improvements in wellbeing, but many had challenges in using quantitative measures.

- The projects reported positive mood and emotions, increased confidence and self-esteem, and reduced loneliness among other outcomes.

- There were eight creative pathways to wellbeing – the combination of contexts and mechanisms that made a difference.

- The case studies contained ‘thick’ description and practice expertise which provided new insights into existing evidence on creativity and wellbeing.

- The synthesis approach is a valuable method to draw together learnings from practice which would otherwise be hidden. This requires comparable, structured and rich case study data.

Background

Project case studies are a quick and proportionate way to share learning from real-world activities and delivery. They present complex findings in an accessible way, and provide practitioners’ perspectives on how activities have made a difference. But their use is often limited to showcasing an isolated example or positive story of change. The untapped strength of case studies lies in what they tell us when we look at them as a body of evidence, and explore common and contrasting themes across them. Synthesising a set of case studies can draw out the processes and activities that work in real-life settings and providing transferable learning.

What we did

We looked at a set of ten creative projects funded by Spirit of 2012 between 2015 and 2023, in England, Scotland and Wales. The activities included making music, creative writing, dance, film-making, singing, art-making and crafts.

We looked at the following projects:

- Bay Create (Whitley Bay Big Local, 2021-23)

- Creative Minds (Youth Cymru, 2018-20)

- Critical Mass (Birmingham 2022 Organising Committee, 2021-22)

- MyMusic Northamptonshire (Northamptonshire Carers, 2019-21)

- My Pockets Music (My Pockets People CIC, 2018-22)

- Our Day Out (Creative Arts East, 2016-22)

- Seafarers (Stopgap Dance Company, 2016-19)

- Sound Out! (Jack Drum Arts, 2019-21)

- Tàlaidhean Ura (Fèis Rois, 2019-21)

- Viewfinder (Beacon Films, 2015-21)

You can find more information in our technical report.

The projects all aimed to improve wellbeing, alongside other ambitions such as reducing loneliness and isolation, improving confidence, and increasing participation in arts, especially for excluded groups. We wanted to know which contexts and mechanisms were associated with these outcomes in these creative projects, so we could identify the pathways which could lead to wellbeing. Using evidence from project evaluation and monitoring reports, we built a rich picture of carefully designed interventions which used inclusive approaches to give creative opportunities to people to support their wellbeing.

Methodology

We used an adapted version of A Guide to Synthesising Case Study Evidence (2021), and the conceptual framework developed for our Scoping review on creativity and wellbeing (2024) to guide our analysis.

What makes a good project case study?

Project case studies are most useful when they include information on:

- The organisation, the partners and the people who delivered and evaluated the project

- The project activities, setting, and circumstances

- The participants, including their motivations, recruitment and circumstances

- The outcomes that were achieved, and what else was learned as a result of the project

- Crucially, case studies should include ‘thick description’.

What’s the difference between ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ description?

A ‘thin’ description is factually accurate, but lacks context or detail to explain the significance of the facts. An example of ‘thin’ description would be: “A total of 15 older women attended the start of the 6-week exercise class, but by the end 5 had dropped out.”

A ‘thick’ description doesn’t just describe what happened, but also says what the context was, and tries to explain the significance of the facts. The ‘thick’ description of the same facts might look like this instead: “The project attracted a lot of interest from mainly retired older women who wanted to improve their fitness for a number of reasons, such as because they were referred by their GP, or because they were struggling to play with their grandchildren. The 15-strong group started positively, with most of the women reporting that they were looking forward to feeling better after exercise. However, over the 6-week course, five women decided to stop attending the classes. Three of them had moved onto lighter exercise that was easier on their joints, and the others could not be contacted for feedback. It’s possible that they felt that they weren’t keeping up with the others, as they had reported this to the instructor earlier in the course.”

Measuring wellbeing

Many projects reported challenges in using the ONS4 and other quantitative measures in their learning. Several of them chose measures they considered more suitable for participants, or developed their own. Some of the key difficulties reported by organisations in relation to the quantitative measurement of wellbeing included:

- The challenges that certain participant groups face when interpreting concepts used in the measure, in particular ‘satisfaction’ and feeling like your life is ‘worthwhile’ or concepts that do not fit with a social model of disability.

- The misleading nature of wellbeing scores when samples are small and a radical change in circumstances for one or two participants has a large effect on average group scores before or after an intervention.

- The effects of Covid-19 on data collection, including low completion rates, particularly for participants with caring responsibilities, long-term physical and/or mental health conditions.

- The perception of questionnaires as ‘tests’ of an individual’s ability or progress made, or an assessment of their continued eligibility to access the project.

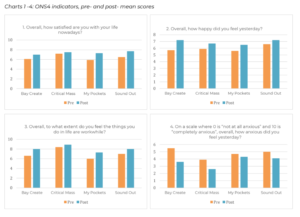

Several of the projects tackled these challenges head-on, including making adaptations for learning-disabled participants, or for adults with dementia or cognitive disabilities. All of the projects supplemented a quantitative measure of wellbeing with qualitative data in the form of interviews, focus groups, or participant feedback. Although the quantitative measurement of wellbeing wasn’t the focus of this case study synthesis, ONS4 data can strengthen the insights from the qualitative evidence. We analysed four of the case studies’ quantitative data and found improvements in all four measures, with a slightly greater change in Anxiety and Life Worthwhile measures.

The effect of Covid-19

The outbreak of Covid-19 and the resulting lockdown restrictions and shielding advice affected seven out of the ten projects. All of the projects expected to be able to deliver activities in person, mostly in community venues or outdoors. Consequently, these projects had to either delay their activities or move them online, usually to zoom sessions.

In terms of access to activities, the move to online delivery had mixed effects on delivery and participants’ experiences. Several projects describe that offering online activities made them more accessible to people in rural areas and those with caring responsibilities. However, projects for both older and younger people, and those with learning disabilities, felt that lack of digital skills and confidence could exclude participants. There was also a perceived risk that projects lost their place-based identity).

Organisations and facilitators had to adapt quickly and learn new skills, as did participants themselves. Recreating the conditions of in-person sessions online was skilled and thoughtful work, and proved harder for some activities than others. Some projects quickly supplemented their original offer with activities that complied with the Covid-19 restrictions.

Creative pathways to wellbeing

The contexts and mechanisms that enabled these creative projects to achieve wellbeing can be understood as creative pathways. We found eight distinct pathways that cut across the case study evidence.

The project evidence suggests that some of the personal pathways to wellbeing may be particularly relevant to specific groups.

- Meaning, escape, distraction and stress-relief were discussed in relation to those with caring responsibilities and those with mental health difficulties.

- High levels of physical challenge leading to pride, increased confidence and aspirations in the context of dance projects were discussed in relation to disabled participants.

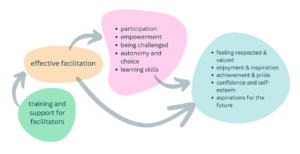

Effective facilitation, mostly by artists, unlocked a range of other mechanisms that led to a number of important personal outcomes:

Elements associated with facilitation:

- It was inclusive (by respecting, encouraging and celebrating participants), and responsive (by providing structure but being flexible).

- It involved respecting participants, celebrating their work, and providing flexibility and support within appropriate structures

- Over-focus on participant problems during sessions may exacerbate them

- Professional artist skills enhanced experience of and outcomes from projects

- Training and support for delivery staff is important to ensure inclusive facilitation

Dance practitioners taking part in the training did sometimes find it difficult to take this initial training, absorb it fully and then enact it in their own teaching straight away without sometimes needing a bit of guidance and support to help the process run smoothly. This was more to do with how the ‘embedding’ process happened and not to do with quality of teaching or enthusiasm, but it is very important and so it was well worth providing support for new teachers in order to help them through that. (Seafarers).

Socially supportive environments and contact led to more engaged and creative people, and led to a number of outcomes. However, the type of social contact didn’t always work for all participants.

Socially supportive environments and contact led to more engaged and creative people, and led to a number of outcomes. However, the type of social contact didn’t always work for all participants.

Key elements of social environment and contact:

- Creating welcoming and accepting spaces which were empathetic and understanding facilitated social connection

- In turn, a socially supportive environment and social connection could motivate continued engagement and support creative development

- Spending time with others ‘like me’ led to feelings of being understood and being safe to share feelings and experiences

- Continuity of people and spending enjoyable, fun time with others fostered social connection and other personal outcomes.

- Creative practice supports communication and connection.

- Social connections among participants may also be limited to weak ties.

- Unsupportive social experience at projects may harm sense of connectedness.

‘I liked being in an environment where everyone knew my situation and they could get me.’ (MyMusic Northamptonshire)

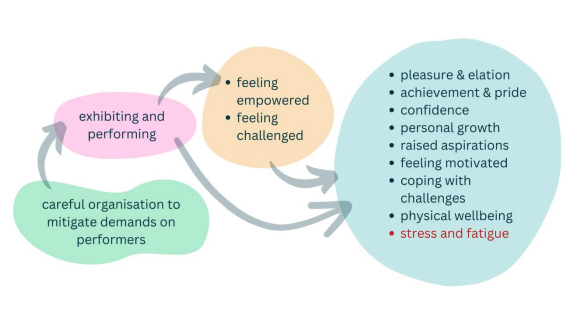

Exhibiting art or preparing and taking part in performances provides a pathway that is unique to creative activities. It led to participants feeling empowered and challenged, leading to a range of outcomes. Stress involved in preparing to perform may be mitigated by good organisation and communication.

Key elements of pathways involving performances and exhibitions:

- Performance or sharing of creative outputs can be challenging, an opportunity for achievement and for celebration of that achievement.

- Performing can place demands on participants, risking that they may opt out, be put under physical and emotional stress or not cope on the day.

- Taking part in professional standard performances can lead to elation and pleasure, pride and sense of achievement; learning to cope with challenging situations and emotions; and raised aspirations.

- Good organisation and communication around events can mitigate stresses placed on performers.

‘There’s one girl who’s got a stunning singing voice but is also really shy. She’s been able to do some performances….She might not be able to perform in front of anybody, but she did build that confidence up to be able to perform, which for her is a big step.’ (My Pockets Music)

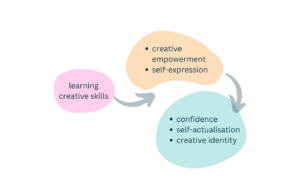

Learning creative skills increased supported creativity. As such, it allowed participants to express themselves, to fulfil their creative potential, and to develop or rekindle their creative identity.

Key impacts of learning creative skills pathways:

- Learning creative skills led to increased confidence which, in turn, encouraged creative use of those skills.

- Learning creative skills enabled self-expression and underpinned creative self-actualisation.

I am trying to build a more confident spurt in me – I can use my new skills in other ways. (Viewfinder)

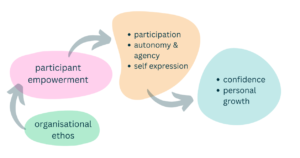

Projects empowered participants to exercise independence and leadership, shape their creative activity and to express themselves.

Key elements of empowerment:

- Individuals were empowered to participate in and influence creative activity and process and also to express themselves

- Individuals were empowered to take on leadership roles, gaining experience and understanding which increased their confidence.

Participants appeared to be much more vocal (and in some cases demanding) of their (creativity-related) wants and needs. (Critical Mass monitoring form)

The model of the ‘Legacy Group’… supported beneficiaries into emerging leadership. Participants increasingly took ownership of the group, determining session content and repertoire, and developing a shared, collaborative style of leadership. (Sound Out! monitoring form)

Meaningful activity provided restorative time away from responsibilities, and distraction and relief from worries leading to a number of outcomes.

Key elements involved in this pathway:

- Participation in creative projects provided a positive, meaningful dimension to life which was an antidote to boredom or to social isolation and loneliness.

- Involvement provided carers with stimulating, restorative time away from caring responsibilities which could make it easier to cope.

- For some participants under stress or with mental health problems, creative engagement was calming or immersing and acted as a distraction from worries or provided relief through self-expression.

‘It gave me something to get out for, because you know it can be so easy to shut yourself away, and you know, not bother to do anything. You know you have got to have something to live for which I think is why these groups have been so, so brilliant. I can’t really say much more than that, because it’s, you know it’s true it’s meant an awful lot to my life.’ (Our Day Out)

‘…as you get older, there’s less and less time for creativity, as work and caring responsibilities take over. So this was an opportunity to get into a rhythm again.’ (Tàlaidhean Ura)

Feeling challenged at an appropriate level encouraged engagement in activity and meeting a challenge provided a sense of achievement and increased confidence. Feeling challenged could be accompanied by stress and fear.

Key elements of this pathway:

- Meeting a challenge posed by creative activity – including to overcome fear – could lead to a sense of achievement and pride and to a growth in confidence.

- Challenge needed to be at the right level: not too much but participants may be underchallenged or avoid challenge altogether.

- Facilitators had to balance comfort/nurturing and challenge.

Getting the balance right between developing work that would positively impact on wellbeing whilst also encouraging people to do something that pushed them outside of their ‘comfort zone’ was an ongoing challenge, across the age ranges. Many older participants were happy to keep the activities simple: e.g. colouring in, as they felt that they were being creative but could concentrate on the chat and social side of the get together. However, it was the more challenging activities that led to a boost in the confidence of participants. (Bay Create)

Physical movement was a feature of dance and music and movement activities, and was related to physical and mental outcomes.

- Physical activity within dance/movement projects was fun, increased fitness and could mitigate body image concerns.

- It could also cause fatigue.

‘It makes me think I can achieve anything in dance, no matter what my body shape.’ (Seafarers)

‘Throughout the year I’ve felt my strength increasing and I feel much fitter with stamina improved.’ (Critical Mass monitoring form)

Conclusions

Personal wellbeing has provided common ground across Spirit’s funding strands, and this consistency has allowed for cross-cutting analysis of Spirit’s impact on wellbeing across different projects over time.

The case study synthesis approach allowed us to identify the multiple pathways to wellbeing and demonstrate the complex way in which these ten projects created benefit. We began to draw out how certain pathways are more relevant for specific populations (in particular carers and disabled people).

This approach to bringing together evidence from practice values the rich learnings of people who deliver activities in their own words. It adds depth and complexity to existing academic research and identifies how and why activities can lead to wellbeing.

This makes this methodology a valuable tool for funders and policy makers to draw out valuable learnings from practice, so they can better support effective activities.

Recommendations

Recommendations for funders and policy makers

- Support a range of creative activities, especially those that are inclusive and empower participants.

- Support projects to develop strong partnerships, including giving time and resources where needed.

- Where appropriate, encourage projects to collect quantitative data on wellbeing using robust measures like the ONS4, but be flexible and support projects who find these measures challenging to use.

- Continue to support projects where professional artists deliver creative projects, and encourage training and other support to be put in place to support skilled facilitation.

- Explore the role of peers in creating wellbeing outcomes, including researching what enables good peer support.

- Use a case study synthesis approach to consolidate and amplify learning and evaluation data from a set of individual projects with a common focus.

Recommendations for practitioners

- Tailor projects to make sure people’s differences are valued, that they feel included, and that they are able to make decisions about the activities.

- Continue to work in partnership to reach people who would otherwise not take part in creative activity, and whose wellbeing may be low.

- Explore what wellbeing means in your context, population and activity.

- Continue to use a range of approaches to understand the difference your project makes to people’s wellbeing.

- Use creative expertise and inclusive facilitation skills to maximise the wellbeing benefits of creative and social experiences.

- Provide an appropriate balance between a relaxed, nurturing and a challenging, productive environment.

- Use a case study framework to support sharing of valuable data and learning from your project.

Using case study synthesis to learn from practice

This project showed the value that a body of case studies can provide in understanding how and why wellbeing outcomes can be achieved.

Developing case studies is a proportional and structured way for projects to communicate their learning, which values their unique insights. Looking across a group of studies can help funders make sense of otherwise disconnected evidence.

However, this synthesis approach is not yet widely adopted by charity funders and commissioners. We recommend that funders:

- Use this case study synthesis methodology to understand their impact across a set of projects, so that enabling contexts and mechanisms can be identified across very different projects.

- Encourage the development of good-quality case study evidence from the projects they fund. Provide training and support to projects to develop case studies for learning, including templates, webinars and troubleshooting.

- Support a culture of peer learning through case studies, including creating case study libraries and peer learning and sharing events.

- Share the learning from case study synthesis widely, especially with practitioners. Let them see that their evidence is valuable and valued, and support them to use this evidence to continue to improve their practice.

Suggested citation

MacIntyre, H. and Abreu Scherer, I. (2024) Creative pathways to wellbeing A synthesis of project case studies. What Works Centre for Wellbeing and Campaign to End Loneliness.

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]