Trends in social isolation

Downloads

The quick read

Using data from five British longitudinal generations studies, the research explored social isolation and connectedness:

- within different contexts (household; partnership, family and friends outside the household; education and employment networks; community engagement)

- over the course of people’s lives between five successive generations

The research highlights:

- How social isolation is a multi-dimensional concept, with a variety of dynamic experiences across contexts, generations and life stages.

- The value of longitudinal data in revealing a more complete picture.

- The need to focus on a range of social isolation indicators across contexts and generations to:

1. understand how people compensate for specific types of isolation;

2. understand how broader economic and social factors can affect the timing of life transition points – and trigger social isolation.

Notable insights

- Younger generations are less likely to belong to a club or engage with religious activity, but are more likely to volunteer.

- Younger generations are more likely to live alone than older generations, particularly in

their 20s. - For the oldest three generations (b. 1946, 1958, 1970), most people experienced isolation

in one or more contexts during midlife. - Fewer people in the older generations reported no isolation at all – possibly driven by

slightly higher proportion of women experiencing isolation across two or more contexts e.g., out of education and employment during this life stage, plus another form of isolation. - While fewer people reported no isolation at all in the older cohorts – they were slightly less likely than the younger cohorts to report all four types of isolation.

- Few people, including those in older generations, reported having no regular contact –

at least monthly – with friends and family. - The oldest generation (b. 1946) show an increase in the likelihood of engaging in regular

social activities around age 65. This corresponds with retirement age and being less

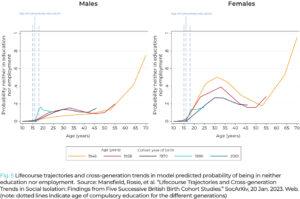

likely to be in education or employment. - Across generations, the probability of females being neither in education nor employment aged 16-31 has decreased, indicating changing patterns of family formation and labour market participation.

This work forms part of a secondary data analysis initiative (SDAI) to address evidence gaps in our understanding.

Background

Despite an increase in policy interest, there is little evidence documenting the associations between social isolation, loneliness and subjective wellbeing across our lives and between generations.

Led by Prof. Praveetha Patalay, this research project aims to address this gap, while also generating a range of comparable measures of social isolation for future research that uses UK generation data.

Insights will help enable the identification of key life stages and contexts where social isolation interventions should be delivered.

This briefing document focuses on synthesising findings and recommendations from the project’s first report: Lifecourse Trajectories and Cross-generation Trends in Social Isolation.

By investigating social isolation, we shift the focus from individual to structural factors that include broader economic and social conditions. This is a necessary first step in identifying concrete policy, community and societal actions we can take to reduce isolation and loneliness.

Social isolation is an objective condition (d’Hombres et al., 2021; Huisman & van

Tilburg, 2021). It can be quantifiably assessed by the number and frequency of social connections and interactions, for example how often someone meets up with their friends, or how many people they live with.

Loneliness is a negative subjective feeling when we feel a discrepancy between our

actual and desired social network, perceiving the quantity or quality of social

relationships to be inadequate (Perlman & Peplau, 1984; What Works Centre for

Wellbeing, 2019). It is assessed through self-report questionnaires.

The two concepts are related but distinct dimensions of social relationships. It is

possible to feel lonely despite being socially connected, and to feel content in solitude.

The data

We analysed data from 73,847 individuals (48.5% female), in five successive generations born in 1946 (N=5,362), 1958 (N=16,742), 1970 (N=16,950), 1989-90 (N=15,562), and 2000-01 (N=19,231).

This research used data from age 10 (i.e. adolescence) onwards due to availability of self- reported measure and greater independence of individuals from adolescence onwards.

This data is taken from five different longitudinal studies:

The value of longitudinal studies

The majority of published research on loneliness and social isolation looks at individuals’ experiences at a single time point or over a short period. It also often focuses on older populations.

In contrast, longitudinal population-based studies have the unique advantage of providing insights based on the same individuals across time. This allows us to see how the same people experience isolation and loneliness over different stages in their lives.

By comparing longitudinal data, we can see how different generations experience similar life stages.

What was done

A multi-context approach

Some people’s social contact is focused on interactions with family and/or friends, while for others there may be more of a mix. For example, engaging with colleagues at work, taking part in community activities or interacting with those they live with.

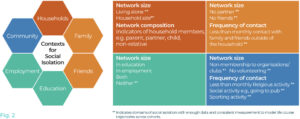

Where available, information was used across the generations on social isolation to generate comparable objective indicators for the following contexts:

1. household

2. partnership, family and friends outside the household

3. education and employment networks

4. community engagement

This involved a process of identifying common variables and derivable data points across timepoints and generations.

The focus on several contexts helps to capture the complexity of social isolation and explore possible ways that social and economic changes over the last century have shaped peoples’ experiences.

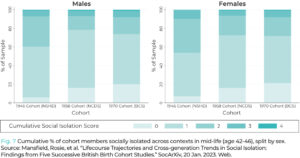

To examine cross-generational trends, we generated a cumulative social isolation score for people in their mid-40s (ages 42 to 46). This life stage was chosen because the 1946, 1958, and 1970 generations had information across all social isolation contexts, enabling a comparable total score to be calculated.

What was found

Key findings are summarised below by isolation context.

Household

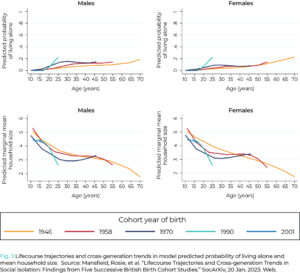

Overall, the probability of living alone across the lifecourse was relatively low compared to other types of isolation.

Younger generations are more likely to live alone across their lives compared to older generations. For the generation born in 1990, there was a sharp increase in the probability of living alone during their early 20’s. This may be due a societal shift away from leaving the parental home to form own relationships and family, and towards leaving the family home for further education or employment.

Females were more likely to live alone in later life. This is in line with previous research and could be due to outliving partners. Males have a higher probability of living alone in early to mid-life.

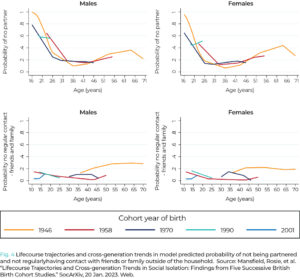

Partnership, family & friends

The oldest generation (b.1946) was more likely to report no contact with friends and relatives outside the household between the ages of 40 to 50, compared with the generations born in 1958 and 1970.

Even so, older people showed a high probability of regular contact – at least monthly – with friends and family outside the household, even when living alone in late adulthood.

Males were slightly more likely to not have regular contact with friends and family outside the household in later life, with a decrease in regular contact from age 35-70. For females, contact remained more constant.

Education & employment networks

In the oldest generation, females were more likely to be out of education and employment in older age, especially after state retirement and pension age.

This is an example of the compensatory effect: as the likelihood of social isolation increases in one context (education and employment networks), it decreases in another (the community engagement context). This also indicates a change in experience across domains at a transitional life stage.

Across generations, there are large differences between males and females in early adulthood (age 16-31).

Across generations there is a decreasing trend in the percentage of women out of education and employment in early adulthood (age 16-31), likely due to changing patterns in labour market activity and childcare.

The peak of being out of employment or education has also slightly shifted right, perhaps reflecting people starting families later.

Community engagement

Regular social activity in the oldest generations decreased in adulthood and then increased post retirement age of 65.

The oldest generation show an increase in the likelihood of engaging in regular social activities around age 65. This corresponds with retirement age and being less likely to be in education or employment. This may be linked to an increase in leisure time.

Recent generations (b. 1990, 2001) had a higher probability of not belonging to a club or organisation.

Younger generations are more likely to volunteer than older generations, particularly from mid adulthood onwards.

Regular religious activity has become less common across generations.

Regular sporting activity was less likely for females in the younger generations, whereas the gender difference was less pronounced in the older generations.

Overall

Overall, there is no clear pattern of increased or decreased isolation across time and contexts.

Older generations showed a high probability of regular contact with friends and family outside the household, even when living alone in late adulthood.

There was a steady increase in the percentage of people experiencing no social isolation across generations. This could be driven by a greater number of people experiencing multiple forms of isolation in the oldest generation, specifically a slightly higher proportion of women experiencing isolation across two or more contexts, such as being out of education and employment during this life stage plus living alone.

Although the number of people experiencing all four types of social isolation was small across generations, there was a slight increase in younger generations.

Research implications

Social isolation is a multi-dimensional concept, with a variety of dynamic experiences across contexts, generations and life stages.

While living alone can be an indicator of social isolation, many single household occupants may compensate by being more socially active in other contexts. For example, by joining a community group. Consequently, a single measure, such as living alone, is an inadequate way of understanding social isolation.

A context-based approach that also considers gender and age can provide greater insight into experiences of social isolation. It can help identify those at greater risk of low wellbeing and increased loneliness: those who are isolated in multiple contexts.

These individuals are particularly vulnerable at transitional points, such as divorce, bereavement, unemployment or new parenthood, and may be more impacted by structural changes such as reduced funding, resulting in the reduction in number of opportunities or places to socially connect.

Using longitudinal data, which captures some of these transition points, reveals a more complete picture of the most common types of social isolation and how they are experienced.

The harmonised social isolation measures developed as part of this work will help develop further nuanced understanding of social isolation by enabling it to be examined at different life stages, across generations and in different contexts.

Recommendations for putting evidence into action

Researchers, policymakers and practitioners can adopt a lifecourse lens to explore contexts, using generational perspectives. Specific recommendations by sector are

suggested below.

Adopt a range of approaches to consolidate evidence on the contexts, mechanisms and

drivers of social isolation across life stages and generations.

These include:

- Social isolation’s relationship with wellbeing and loneliness, including the role of transitional life moments

- Factors that may explain a decline in community and religious activities, including reduce access to clubs and organisations and wide generational shifts.

- Mechanisms that enable changes in social isolation, for example, through participation in clubs and organisations, and in digital contexts such as online gaming.

Take a holistic view of life experiences and conduct research using a range of social isolation indicators.

In particular, the following should be further investigated:

- The role of contexts as potential moderators or predictors of social isolation e.g. single- person households.

- Alternatives to the use of ‘living alone’ as a single proxy for a lack of social connectedness or support.

- Whether using age 65 as a proxy for retirement is an appropriate indicator.

Consider structural societal differences which define the timing of life transitions.

Develop ways to address isolation within and across contexts of social isolation. For example, to compensate for increased numbers living alone, increase opportunities for community groups and reduce barriers to participation via funding and programme design.

Explore how infrastructure can be adapted to support more social and physical health across the lifecourse, from a place of prevention rather than intervention. If this is in place it may buffer against changes to individual circumstances or transitional phases which might fracture personal social networks. For example divorce, bereavement, new parenthood, relocating.

Employers may consider developing a workplace wellbeing strategy that includes specific support for employees managing transitional phases.

Take an anti-ageism approach to supporting those transitioning from employment into retirement to ensure people are able to continue contributing and lead active lives.

Think about the different factors that can affect whether people are isolated at different times in their lives, and how this may change over time. Take into account how your service can fit into their lives now, and how it might need to adapt if circumstances change.

Consider involving people in clubs and groups, recruiting them into volunteering, or encouraging them to take up hobbies with others as a way to help them deal with the higher risk of isolation that retirement brings.

Think about how you can involve people who have stopped working due to new

parenthood, unemployment or sickness in social projects, to buffer them from the reduced social contact of leaving work.

Citation

Donnelly, R., Hey, N., McIntyre, H. Social isolation over time. Briefing, June 2023, What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

Find out more

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]