What helped the UK cope with the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns?

Downloads

Quick read: what you need to know

- Staying connected to friends and family was the most important coping mechanisms identified by people during the UK’s first lockdown.

- Gardening and exercise had the biggest association with supporting people’s wellbeing, while following Coid-19 related news had the most negative effects on our wellbeing

- Different people have different coping strategies. Some of us prefer to problem solve, while some of us try to avoid our difficulties. Others rely on emotional reframing or the social support of their friends and family.

- It is important to recognise which strategies are more helpful for our mental health and long-term wellbeing.

- Research has clearly shown that physical activity such as exercising or gardening has improved mental health and wellbeing during the pandemic.

- Some people have also used arts and cultural engagement as a way to cope.

- There may be long-term impacts on our wellbeing from negative changes to eating, drinking alcohol and gambling behaviours. This is especially the case for those who were already at-risk from these issues. A wellbeing-based recovery will depend on helping people access and choose healthier styles of coping.

Covid-19, coping and wellbeing

How did we cope?

Coping is broadly defined as the cognitive and behavioural efforts that individuals employ to manage stress. These behaviours are often referred to as strategies and may either be conscious or unconscious.

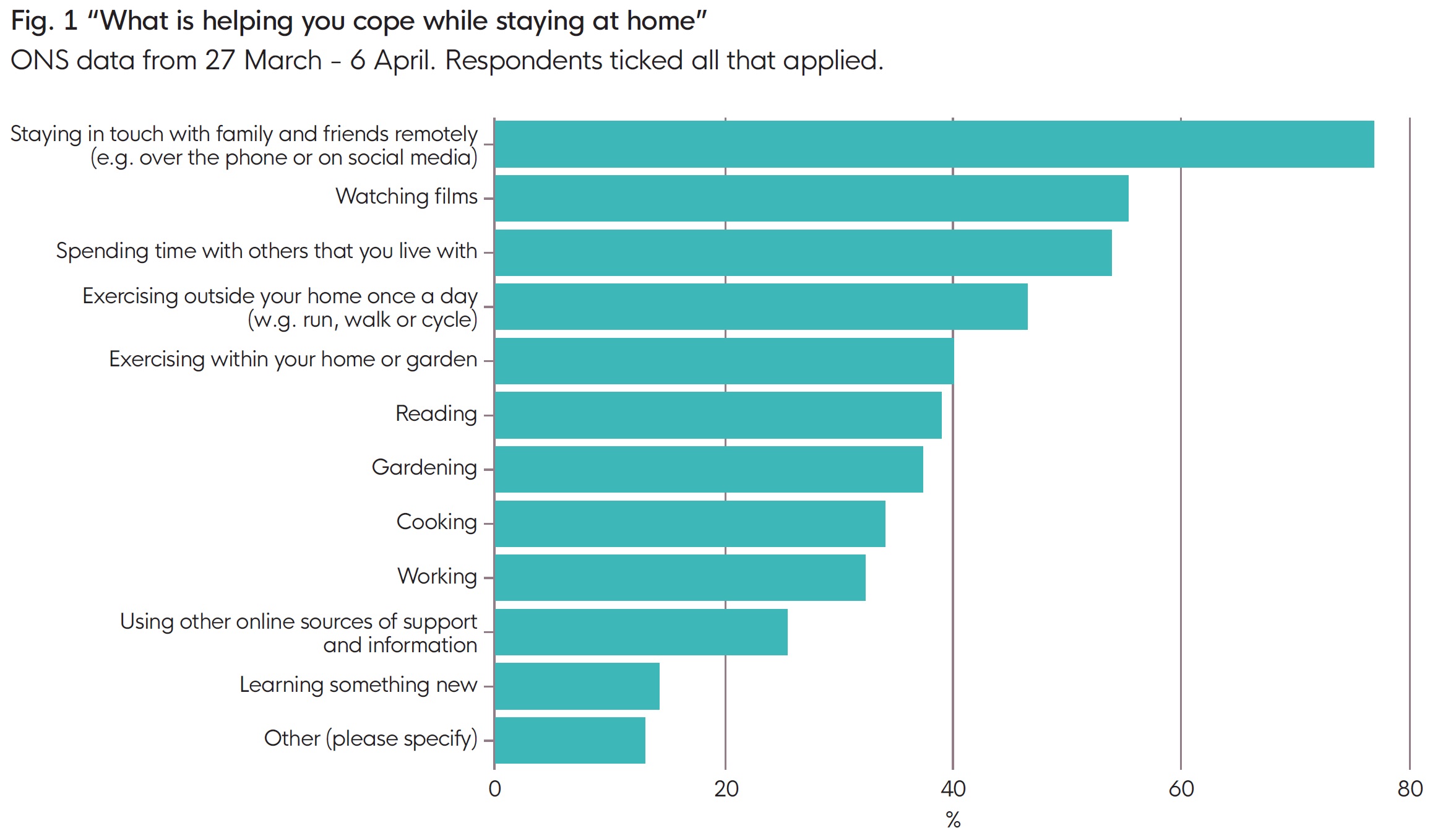

People in the UK have used different approaches to help them cope with the stress and changes associated with Covid-19 and the restrictions of the lockdowns. Data from the start of the first lockdown in March and April 2020 showed that more than three quarters of people found that staying in touch with family and friends virtually helped them to cope.

Source: ONS data from 27 March – 6 April. Respondents ticked all that applied

Different coping strategies can have different effects on our wellbeing. For example, avoidance strategies, such as withdrawing from others, watching films or using harmful substances, may be helpful in reducing short-term stress, but do not directly reduce the stressor and can cause individuals to feel hopeless or to blame themselves. In contrast, problem-solving strategies, such as that used in cognitive behavioural therapies, can be helpful for long-term wellbeing.

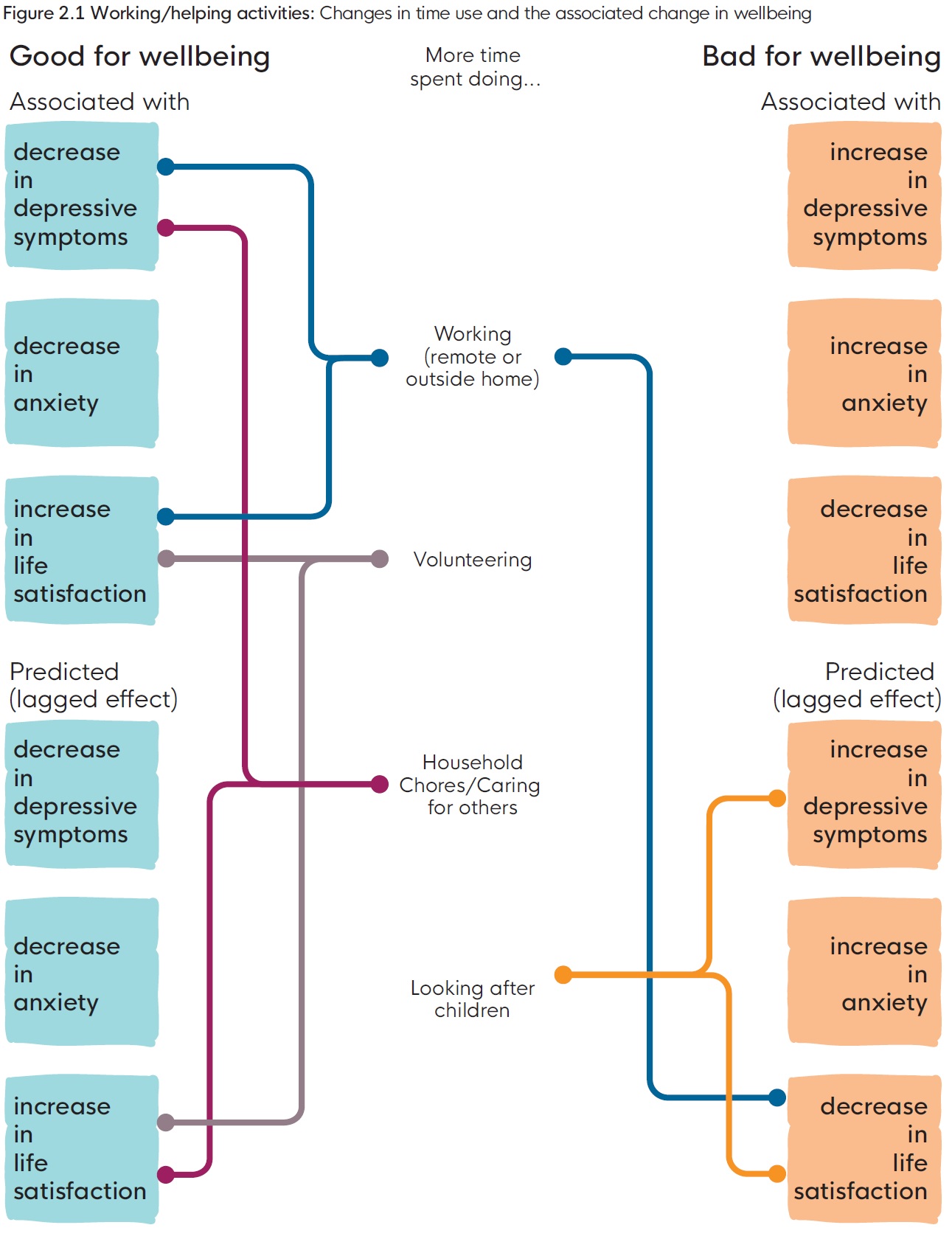

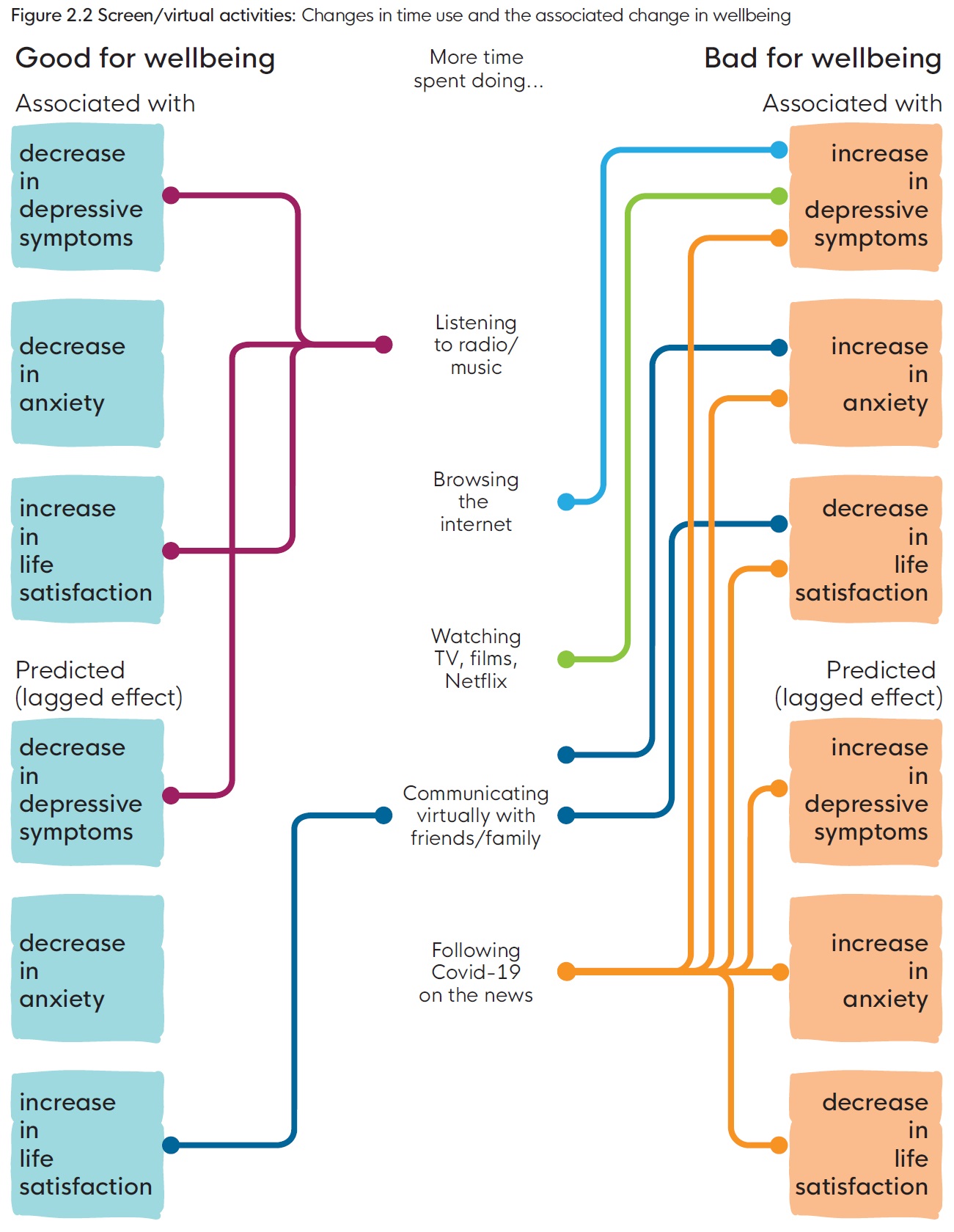

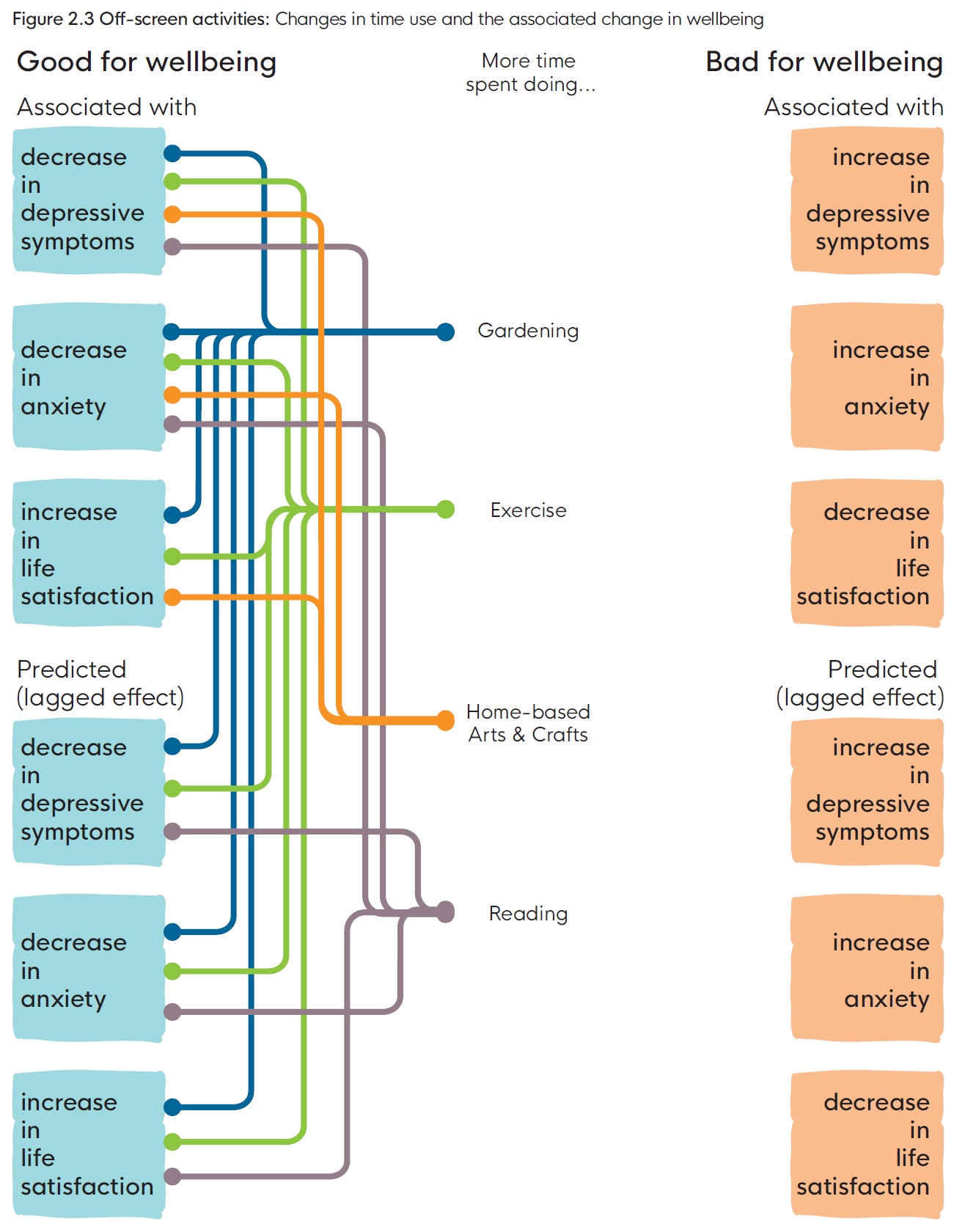

Researchers of the COVID-19 Social Study examined the relationship between how we spent our time on different activities during the working week (Monday-Friday) and the impact on our mental health and wellbeing between the end of March and the end of May 2020.

The three charts below (fig 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3) show where the data found an association between a reported increase in time spent on certain activities, and changes to their wellbeing outcomes – depressive symptoms, anxiety and life satisfaction, when controlling for other factors.

The researchers also conducted an analysis which tested the lagged effect of coping strategies. They found that a reported increase in time spent on these activities could predict a change in a person’s wellbeing outcomes, when controlling for other factors.

Source: Bu, F., Steptoe, A., Mak, H. W., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Time-use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a panel analysis of 55,204 adults followed across 11 weeks of lockdown in the UK.

The largest decrease in depression occurred among participants who increased their time spent on:

- exercise, to more than 30 minutes per day

- gardening, to more than 30 minutes per day

- work, to more than two hours per day.

The largest decrease in anxiety occurred among participants who increased their time to 30 minutes or

more per day on:

- gardening

- exercising

- reading.

Different strategies for different people

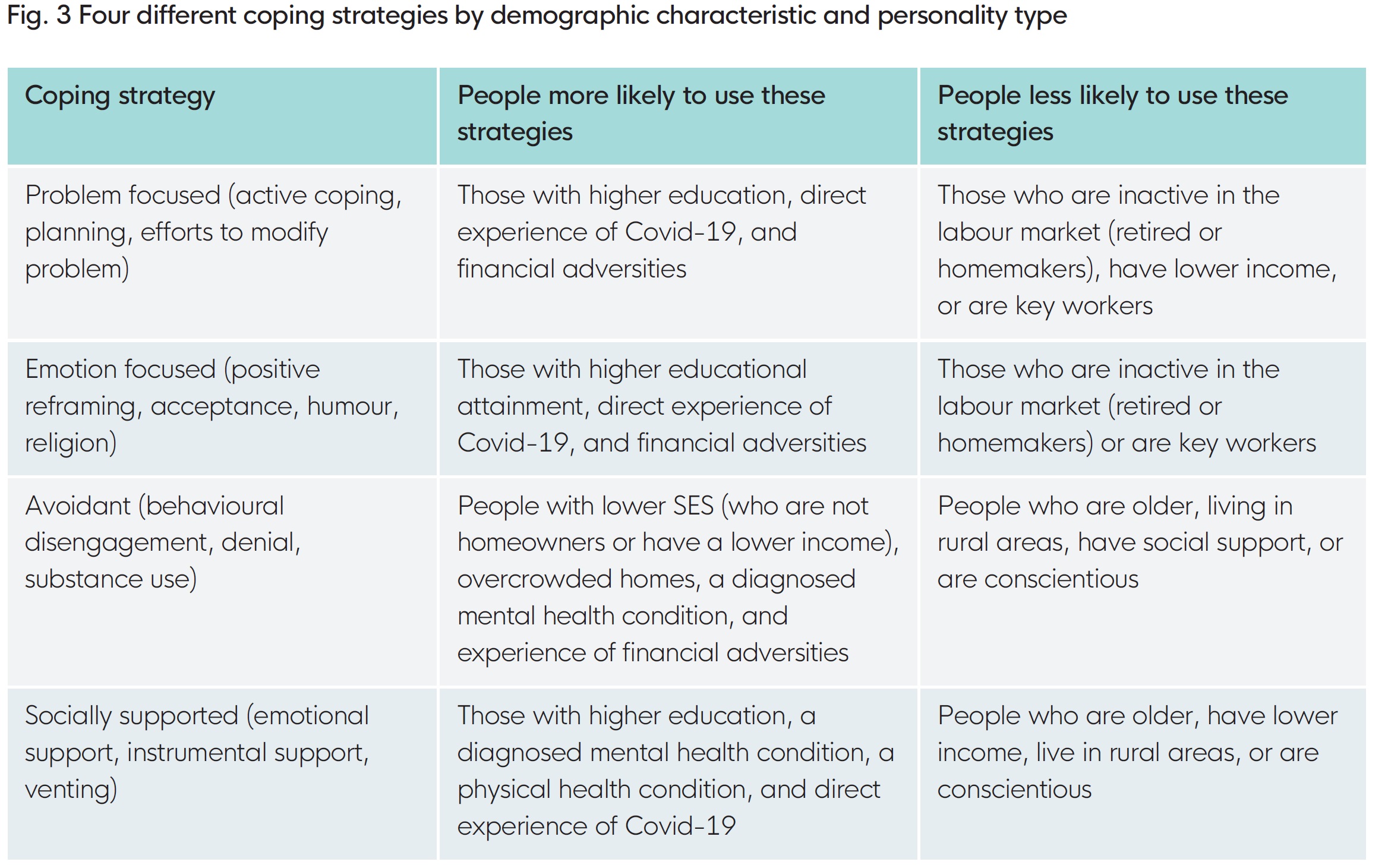

People use different coping strategies depending on the time, money and social capital they have to address their stressors. Individuals’ personality types and the specific adversities they face also influence their choice of coping strategy. By understanding how people are coping during the Covid-19 pandemic we can support them to find strategies that protect and enhance their wellbeing during these times of difficulty and uncertainty.

Data collected during April and May of 2020 showed that predictors of coping styles were the same as before the pandemic, suggesting that individuals’ traits and socio-economic circumstances are at least partly responsible for differences in management of stressors during the pandemic. Women, for example, were more likely than men to use any of the four coping strategies. Figure 3 presents the different coping strategies of different people during the pandemic.

Source: Fluharty, M., & Fancourt, D. (2020). How have people been coping during the COVID-19 pandemic? Patterns and predictors of coping strategies amongst 26,580 UK adults.

People who were worried about negative events that might affect them tended to use a range of coping strategies. Those who actually experienced a negative event were less likely to use socially supported strategies. This suggests that individuals envision handling certain situations more positively than how they actually experience them.

How different coping strategies affect mental health

The COVID-19 Social Study has also shown how our choice of coping strategy can affect our wellbeing. During the first 21 weeks of the UK lockdown, people who used supportive coping strategies experienced a faster decrease in depression and anxiety over time than those who were emotional, avoidant or problem-focused copers. There could be a number of reasons for this. Problem-solvers and emotion-focused copers may have struggled to feel effective given the extreme challenges of the pandemic. However, compared to avoidant copers, they may have eventually experienced better health outcomes over a longer period of time.

Coping strategies also have implications for people with pre-existing mental health difficulties. Those who adopted supportive coping strategies during the pandemic were more likely to experience a reduction in depressive symptoms and anxiety. Researchers of the COVID-19 Social Study also found that engaging in hobbies and activities and staying connected and supporting others were effective coping strategies for people with mental health conditions.

***

The COVID-19 Social Study has also examined how the pandemic has changed our behaviours and activities and how this may have impacted our wellbeing.

Volunteering

Volunteering can enhance one’s sense of purpose, approval from others, and mental and physical health. Between late April and early May in 2020, people in the UK were asked about their volunteering activities. The COVID-19 Social Study distinguished between formal volunteering with existing organisations, providing neighbourhood support, or social action (pro bono) work.

Overall, 12% of respondents reported that they had increased their participation in volunteering during lockdown compared to prior to the pandemic. Of these:

- 19% maintained this higher engagement

- and 7% further increased it 3 months later

Those who were likely to volunteer before the pandemic continued to do so, such as people living with children, females, those living in rural areas, and those with more education and higher incomes. However, data from the study shows that the pandemic has led to an increase in volunteering among other groups. Older people, in particular, were more likely to have increased their volunteering particularly due to Covid-19.

People with a diagnosed physical illness or disability were more likely to do social action volunteering than before, but in activities that could be done from the home, such as internet research. People with a diagnosed mental health condition were also more likely to volunteer formally or for social action initiatives than those without a diagnosed condition.

What we eat

Changes in eating habits can be a type of coping strategy, but dramatic changes in one’s volume of food consumption can be detrimental to health. Data from the first eight weeks of the first UK lockdown shows that a third of people changed their eating habits:

- 16% reported persistently eating more

- 4% did not report any changes in eating during the first week, but their food consumption increased substantially across time

- 8% reported eating more during the first weeks, but progressively decreasing the amount until week eight

- 9% of people reported persistently eating less

People that were most likely to increase their food intake were women, adults aged 30-45 years, people with depressive symptoms and loneliness. Worries about getting sick from Covid-19 were associated with higher odds of belonging to this group.

Health challenges related to eating were likely to be exacerbated. People that reported that they were overweight were more likely to eat more, while those who were already underweight were more likely to report eating less, which was also positively associated with increased depressive symptoms.

What we drink

People sometimes use drinking alcohol as a coping mechanism. During the first couple of weeks of lockdown, just over half of people who usually drink alcohol reported a change in their drinking habits:

- 26% reported drinking less than usual

- 26% reported drinking more than usual

Younger people, females, those with education qualifications past the age of 16, with high annual household incomes, and with an anxiety disorder were more likely to drink more than usual. They were also significantly stressed about their finances and catching or becoming seriously ill from Covid-19.

People likely to drink less than usual were also younger adults, male, of an ethnic minority, had lower annual household incomes, were not key workers, and were more likely to have been diagnosed or suspected of having Covid-19. Like the former group, they were also significantly stressed about catching or becoming seriously ill from Covid-19.

Arts and crafts

While the national lockdown led to the immediate closure of public spaces, galleries, exhibitions, museums, arts venues, and other cultural assets, many providers began offering virtual activities to keep people engaged in digital arts activities. There was also a rapid increase in the sale of crafts materials such as paints and wools.

Changes in arts participation during lockdown were varied:

- 16% of people reported that they had decreased their participation

- 62% had about the same amount of engagement levels before and during the pandemic,

- 22% increased their engagement

Researchers in the COVID-19 Social Study investigated whether people were using home-based arts engagement as a form of coping. They found relationships between individuals’ coping styles and their engagement with the arts. Those who had an emotion-focused coping style were more likely to increase their arts engagement, along with young adults (aged 18-29), non-key workers, and those with greater social support. Those who coped with avoidant tactics tended to decrease their arts engagement.

Gambling

There has been concern that the lockdowns and social isolation may encourage people to increase maladaptive coping behaviours such as gambling. Researchers have examined who was most likely to gamble more frequently.

They found that during the first lockdown, approximately 30% of people had gambled in a range of ways, from playing the lottery to online betting. 20% of these people reported a change in their gambling behaviour since the lockdown:

- 11% reported gambling less than usual

- 9% reported gambling more than usual

People likely to gamble more than usual were highly bored, employed, frequently drank alcohol, and had depression and anxiety. These particular groups may need support to help them adopt alternative coping strategies, especially those who continued to gamble at high rates even when lockdown restrictions eased.

Implications for a wellbeing-based Covid-19 recovery

- How we spend our time matters for different aspects of our wellbeing.

- The time we spend at work plays an important role in supporting our life satisfaction and sense of purpose. The pandemic has changed many people’s working hours and time spent commuting and the impact of the pandemic on employment has been in sharp focus for policy makers.

- Our behaviours and activities outside of working time can also enhance our wellbeing and be protective during times of stress and uncertainty.

- A wellbeing-based Covid-19 recovery will depend on providing individuals access to activities that can enhance their wellbeing and on encouraging behaviours that can improve mental health and protecting the time necessary for meaningful engagement in these activities, particularly for people with limited free time in caring roles and where services have been reduced. Positive activities can include:

- Exercising

- Gardening

- Volunteering

- Arts and cultural engagement

- It will also be important to help individuals manage activities and coping strategies that may be detrimental to their wellbeing, particularly during times of increased stress and among those who are already vulnerable .

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]