Happiness, and the relationships we have with people and politics

Last week, on International Happiness Day, the 7th edition of the World Happiness Report was published. The report scores and ranks countries based on the answer to the Cantril ladder question included in the Gallup World Poll, which asks people to value their lives today on a scale between 0 (the worst possible life) and 10 (the best possible life). Our Head of Evidence, Deborah Hardoon, pulls out the themes on the importance of relationships from the report.

International rankings are always a good attention grabber: Finland comes top, again, with an average score of 7.8; the UK at 15th with 7.1; and South Sudan ranking lowest with 2.9. It’s also, after seven years, possible to see movements in happiness reflecting bigger political,social and economic shifts: Benin showing the most improvement, and Venezuela and Syria the biggest decline.

But, for meaningful understanding and action, looking beyond the scores and ranks of different countries is a more useful approach. asking: what’s behind different people’s answer to this question, within and between countries?

The theme for this year’s report was how people communicate and interact with each other and their governments. This feels like a particularly relevant theme for us to explore in the UK, with loneliness, social divisions and people’s engagement in politics all very live issues and things we are keen to look at in our upcoming research programme.

Relationships are clearly a fundamental determinant of our wellbeing.

- Social relationships are important

The authors of the report estimate the contribution that six different factors have on a country’s overall wellbeing score. They find that social support – people’s answer to the question ‘If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?’ – can explain 34% of the wellbeing score, as explained by the six determinants. This is more than income (26%), or healthy life expectancy (21%).

Professor John Heliwell summed it up at the report’s launch: It’s our shared laughter that’s the magic that makes our lives better.

Giving, wellbeing and pro-social behaviour

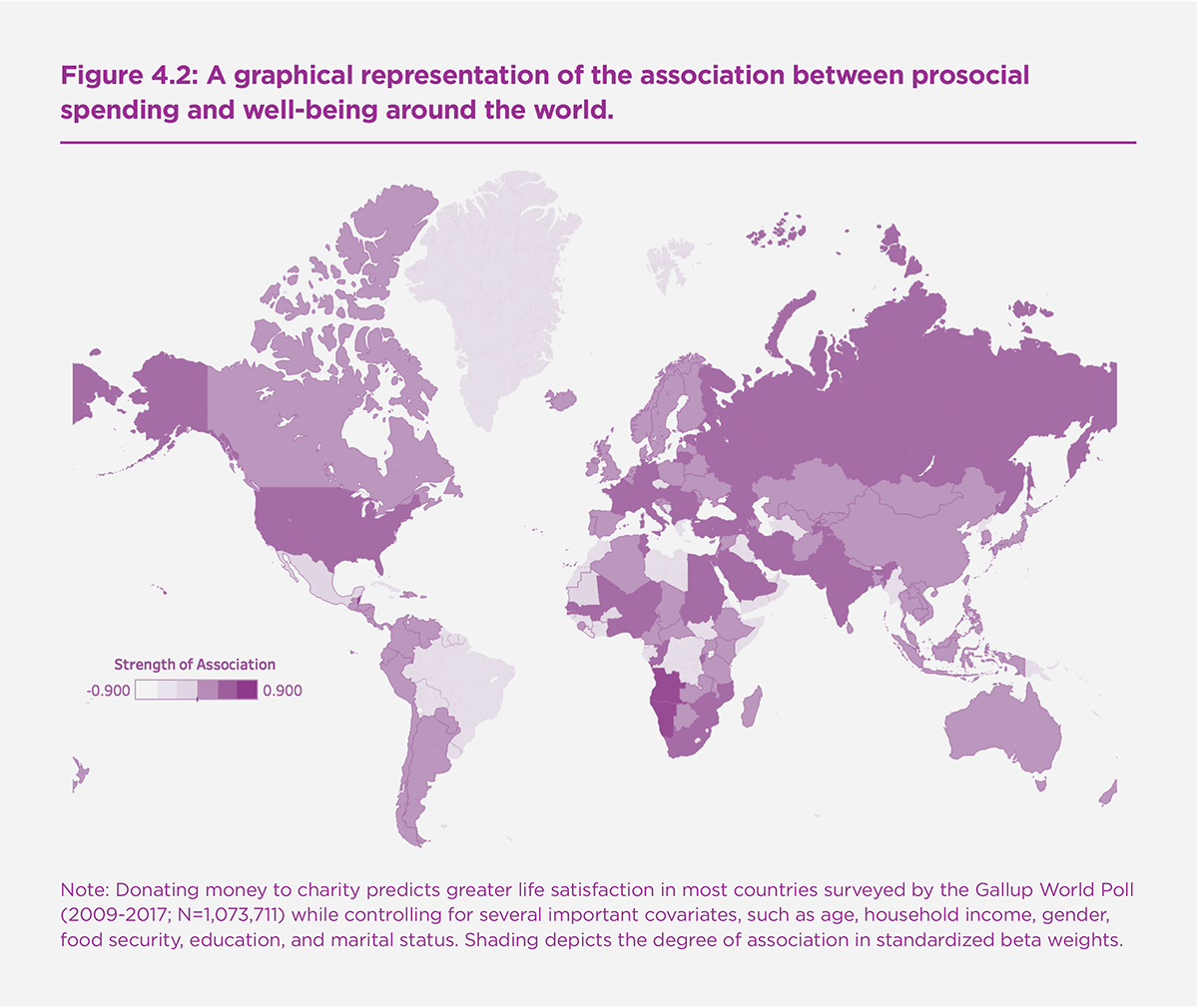

When it comes to our relationships with our communities, the research finds that there is a clear association between wellbeing and pro-social behaviour (giving time and money to others). ‘Give’ is one of the Five Ways to Wellbeing, which has been a popular approach for exploring how different aspects of our lives can improve our wellbeing.

It’s unclear in which direction the causality runs – it could be that happier people are more generous, or that more generous people are happier as a result of their generosity. Either way, this is a call for us to think about how we relate to this aspect, especially as there are potential spillover effects of this pro-social behaviour for the wellbeing of our communities.

Three conditions that count for social relationships

The review of the evidence included in the report finds that we can maximise the benefits from this interaction under three conditions:

- When people are free to choose how and when they help

- When people feel connected to the people they are helping

- When they can see how their help is making a difference.

- Our relationship with our government affects, and is affected by, our wellbeing

We know that better governance can shape our wellbeing, this is demonstrated not only by the contribution that perceptions of corruption has on the model for between country differences, and the importance of trust more broadly for society, but also due to the importance of government policy in shaping all the other outcomes that determine our wellbeing.

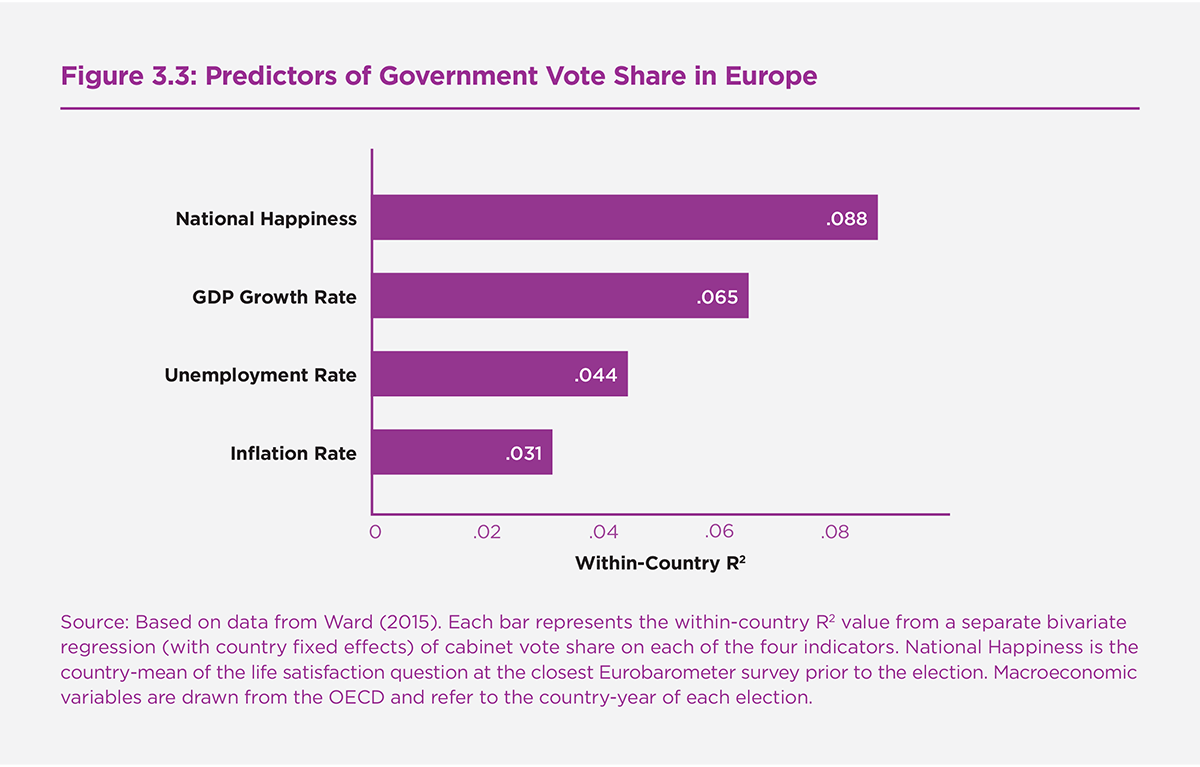

But in Chapter 3 of the World Happiness Report, George Ward looks at the relationship from the opposite direction, and asks whether the level of our wellbeing can in turn shape our governments.

Happier people more likely to vote

Data from the US and rural China show that happier people are more likely to vote. Data from 103 countries in the World Values Survey finds that very happy people are 9.3 percentage points more likely to be interested in politics than not at all happy people.

Happier people vote for the status quo

Somewhat intuitively, people that are happy are more likely to also vote for the incumbent. This has been identified in research using data from the UK’s British Household Panel Survey. This finds that being satisfied with life makes people more likely to vote for the incumbent, and negative shocks (such as widowhood) make people unhappy and less likely to vote that way.

The importance of the ‘hidden unhappy’

This evidence highlights the importance of looking at wellbeing inequalities in a society, identifying and understanding who is more and who is less happy. Because if people that are doing well are more likely to vote, and vote for the status quo, then happy people will remain happy.

Those that are left behind are less likely to vote, or have their voice heard, potentially forgoing representing a critical mass sufficient for a substantive change in policy that might alter their lot. This risks increasing wellbeing inequalities, where the happy perpetuate their own position through power and politics.

My interpretation of the report’s findings is that individuals vote on the basis of their own self-interest and current level of wellbeing, rather than a concern for the wellbeing of others or wider society. However, the research in this area is very new and we are still exploring how wellbeing inequalities and concern for others’ wellbeing can influence voting behaviour.

Wellbeing as a policy goal, especially for the worst off

Either way, these initial findings do build a compelling business case for governments to address our wellbeing through their policies if they want to gain and retain power in a democracy, but we should pay close attention to who’s wellbeing is being invested in and who is missing out. Because as Ward states in the report: ‘the overarching theoretical question to be addressed in this area is the extent to which happiness-based voting is likely to be welfare-enhancing overall’.