Exploring happiness with life online among children in the UK

This week’s blog is from Dr Louise Moore and Phil Raws who are both Senior Researchers at The Children’s Society. It reflects on findings from an exploratory analysis of children’s responses to questions about different areas of their online life included in the charity’s 2020 annual household survey.

The ubiquitous role that digital technology plays in children‘s lives has been amplified during COVID-19 – helping to preserve relationships with friends, supporting schooling and offering entertainment throughout lockdown. But pre-existing concerns about the potential negative impacts, alongside the Government’s bid to improve online safety through new legislation, highlight the challenges of balancing the risks/benefits. The Children’s Society has been looking at children’s digital lives, and how online happiness might be related to other aspects of wellbeing.

The Children’s Society’s 2020 household survey asked just over 2,000 children in the UK about their use of digital technology and happiness with online life. The survey was conducted in April-June 2020 and, as such, reflects views during the first national lockdown. Responses suggested that:

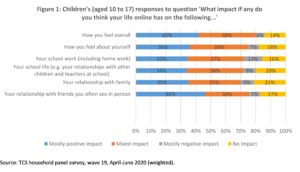

- Perceived impact of online technology is rarely negative. Most children reported either a mostly positive or mixed impact (i.e. a mix of positives and negatives) on other aspects of life (Figure 1). Less than one in ten reported a mostly negative impact on five of the six areas covered. The exception was school work, where 13% identified a mostly negative impact.

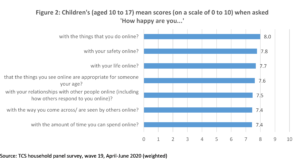

- Children are relatively happy with their life online. Children were asked to rate their happiness with seven aspects of online life. Scores ranged from 7.4 for amount of time you can spend online to 8.0 for things that you do online suggesting most children were relatively happy (Figure 2).

- Children’s responses to online happiness questions are associated with each other and with other wellbeing measures. When The Children’s Society first developed its Good Childhood Index there was comparatively less internet use, so we wanted to consider the relationship between online happiness and other aspects of children’s wellbeing:

- Exploratory analysis revealed some strong correlations between the overall and individual measures of online happiness – e.g. happiness with life online and the way you come across online (r=0.74); and happiness with life online and relationships with other people online (r=0.70). 1

- Regression analysis suggested that, of the six individual measures of online happiness, happiness with the way you come across online, things you do online and relationships with other people online explained the largest amounts of variation in children’s overall happiness with life online. 2

- There were moderate correlations between the online measures and many Good Childhood Index items (e.g. r>0.480 for the overall online happiness measure and all Good Childhood Index items).

- There was also a moderate association between children’s happiness with life online and their overall life satisfaction (based on Huebner). 3 However, when included in a regression model with the 10 Good Childhood Index items, the overall online happiness item did not increase the amount of explained variation or significantly contribute to a model of children’s life satisfaction (based on Huebner). 4

Implications and Next Steps

These findings indicate that most children are relatively happy with life online. Preserving the benefits of children’s existing digital lives, while protecting those who may be vulnerable to harm, will likely require a better understanding of online experiences. However, taken at face value, these findings suggest that nuanced or targeted approaches will play an important part in keeping children safe.

Exploratory analyses seem to indicate that there is some association between children’s online happiness and their responses to existing wellbeing measures. The unique context of COVID-19 may have affected our survey findings, so further analysis considering a wider range of factors – complemented by qualitative research exploring if/how children account for online life in their answers to well-being measures – will be important to help clarify these conclusions.

1 Pearson correlation coefficients reported in this blog were significant at 0.01 level.

2 All items except amount of time you can spend online made a significant contribution at 0.01 level to the model which explained 66% of variation (adjusted R2).

3 A multi-item measure of overall life satisfaction based on Huebner’s Student Life Satisfaction Scale (Huebner, 1991), which consists of 5 items with a total possible score of 0-20. Pearson’s r=0.44.

4 Models containing i) GCI items, and ii) GCI items and happiness with life online explained 46% (adjusted R2) of variation. Happiness with life online did not make a significant contribution to model ii) at 0.01 level.

Our work on children and wellbeing

Listen to our podcast on how the pandemic has affected children's wellbeing, and read about our work to map what measures and tools are being used in the UK to measure the wellbeing of children and young people.