Measures of wellbeing and impact – who decides?

This week, Becky Seale and Catherine-Rose Stocks-Rankin, Public Health England researchers and co-leads of the Unleashing Healthy Communities project in Bromley by Bow, share their perspectives on traditional measurement of community-based approaches to health and wellbeing.

How much time would you imagine is spent in community centres across the land measuring wellbeing? A project manager at Bromley by Bow, and colleague of the last two years, estimates that as an organisation they spend as much as 15,750 hours a year collecting such data.

There are strong drivers for all this measurement. Bromley by Bow, like other community-based models need ‘hard evidence’ of their impact to bring in funding. Academia want it in order to re-balance an evidence base heavily weighted towards clinical evidence and biomedical approaches to evidence generation. The public health community and commissioners want it in order to direct and justify precious investment.

With all this investment of time and energy, are we sure we’re measuring the right things?

Re-balancing the evidence base

There is currently a movement in health equality and wellbeing research to rebalance the evidence base. For instance:

- the Academy of Medical Sciences has asked for research which is developmental and helps to create solutions rather than just describe and define problems.

- Crisp et al say that these solutions need to be led by a multi-sectoral approach which takes account of the knowledge from community and voluntary organisations, social enterprise, patients and citizens as well as the health sector.

- Rutter et al call for more operationalisation of systems thinking in both the design of interventions which address health inequality and their evaluation.

Measurement according to funder-defined outcomes

Our observation from the last two years spent evaluating Bromley by Bow is that it is primarily measured according to funder, academic or think-tank defined outcomes.

Often this measurement is highly fragmented, which means it can’t do justice to the value of the whole contribution that integrated models like Bromley by Bow offer. A funders’ own priorities, the wider evidence base on what is effective and an academic or think-tank’s area of interest are all important. But these sources should form just one part of the way these models are measured.

A radical approach to measuring wellbeing in the community

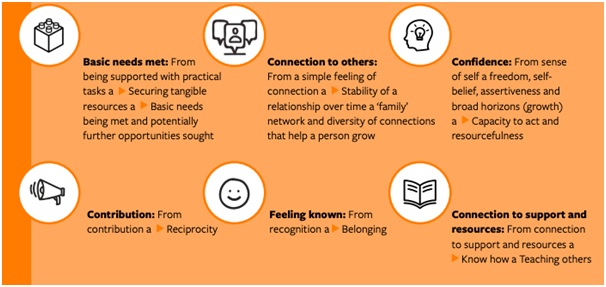

In this blog we would like to offer both our method and our findings as a more inclusive way to measure wellbeing in community-based organisations. We took a radical approach to measuring wellbeing at Bromley by Bow that was rooted in understanding what local people value and what staff say works. This has created a self-defined benchmark of efficacy for Bromley by Bow, via a theory of change and a set of outcomes:

The accompanying theory of change is available in the full report.

Why did we decide on this approach and what value does it offer?

1. Addressing evidence gaps – we wanted to address a gap in the evidence around the impact of the holistic nature of models like Bromley by Bow on wellbeing and on health inequality.

Because our research focused on the whole model, we were able to see themes that cut across job roles, professional identities, and even the organisational boundaries that are part of the model (it is both a group of Health Centres and a Community Centre).

From this we identified that core to the Bromley by Bow model is work that is both about meeting need and offering opportunity. We can see that this mix of work matches what the community say they want and need: they both need a space for tackling urgent issues with their health, housing or debt and they want the space to grow and contribute.

There are times when the balance can be off and people (staff and community members) can feel frustrated with the limits to activities and support which only focus on meeting need. From this evidence, we suggest that it is the combination of meeting need and offering opportunity under one roof that is valuable to wellbeing creation and tackling health inequality.

2. Bureaucracy drawbacks – given that it is not clear that the current suite of ‘KPIs’ are always related to reality, we wanted to create accurate measures that align with how people live their lives and the work taking place day today.

Our research focused on the visible as well as the invisible work that people do in their jobs as well as the enablers and barriers to people’s wellbeing. As one example, local people told us many stories which highlight the impact of unrelenting bureaucracy on existing mental health issues. In turn, GPs showed us how they act as a gatekeeper for information on behalf of their patients, with one commenting “we are the risk sink” for the wider system.

This evidence suggests mechanisms such as connecting people to resources and doing administrative work for them may be important to measure when evaluating community-based approaches to wellbeing.

3. Human interaction: wellbeing rich, time poor – we wanted to create a pathway for collecting evidence and generating knowledge which measures outcomes that are valued by people themselves. This is of crucial importance if strategic decisions are to made off this back of these resources.And because, at a ground level, our observation is that measurement uses precious resources and subtly directs behaviour: it can be both a force for good or an unhelpful distraction.One of the things that emerged from asking people what they value was the opportunity to ‘give and get back’: to contribute as a human being, to form connections through doing so, and to learn and grow.Interestingly, Bromley by Bow grew from such simple acts of reciprocity, from humans creating something together. Yet in the modern day, staff told us that there isn’t as much time as there once was for such exchanges. Bromley by Bow has approximately forty different funding streams all requiring different outputs to be counted. Few of which are related to capturing reciprocal ways of working that build agency and ownership.

This is significant for health inequality, since we know that agency is fundamental to wellbeing. Our assertion is that creating measurement which is targeted to what matters to people can play a role in directing staff and policy makers’ work (and impact) towards the things that count, rather than the things that can be easily counted.

A woven tale of wellbeing

To conclude, when we ask who decides about these measures, we’re asking that from the belief that research and evidence helps policy makers and strategic thinkers to make ethical decisions about creating wellbeing and addressing inequality.

And to do that we stress the importance of genuinely grappling with the complex realities of life, of service delivery, of community development. The wisdom of communities to understand and define what’s valuable and practice knowledge about what works are important benchmarks of accountability, and should be loud and clear in any evaluation of community-based models.