The Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, has acknowledged the ‘vital contribution’ that public sector workers have made during the coronavirus pandemic and awarded above-inflation pay rises for almost 900,000 of them, including teachers, doctors and police officers.

Our new research suggests key workers do face lower pay than the average worker. And many of them also suffer from lower job quality, particularly in terms of the amount and timing of hours worked.

To analyse this, we used data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) to produce a dataset of 25,000 people working in key worker jobs. We compared salaries alongside individual job quality indicators of each key worker profession.

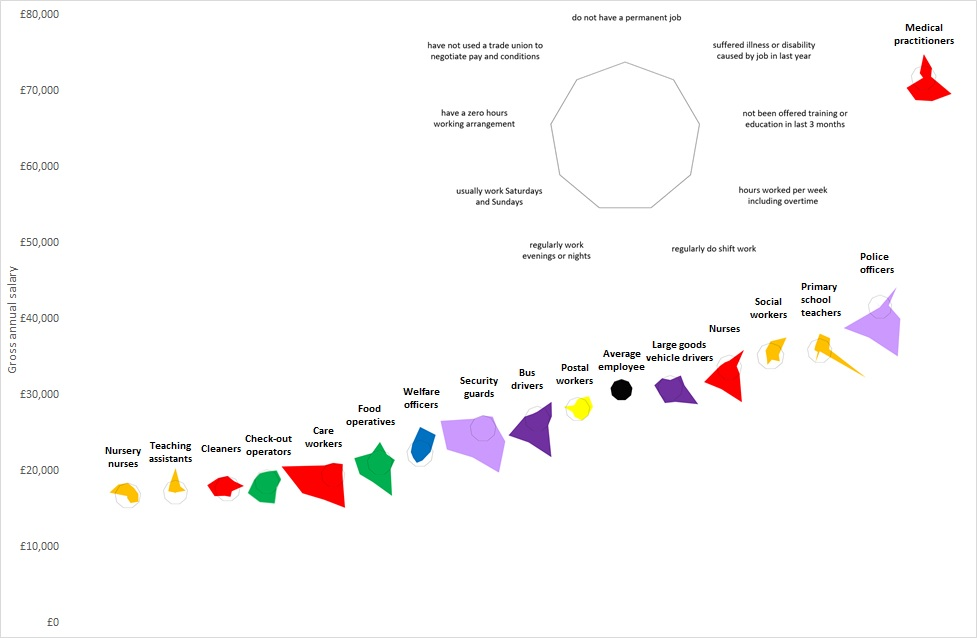

Indicators of job quality* included whether workers are permanent members of staff, on zero hour contracts, work weekends or anti-social hours, part of a trade union, how often they fall ill at work and whether they have been offered any training in the previous three months.

This radar chart summarises the job quality of selected key worker occupations.**

Chart showing the job quality of selected key worker occupations. See more detail in the individual key worker charts in the full paper.

It shows that the jobs which have been identified as having the highest value during the pandemic are often the lowest paid and have more negative job quality indicators.

Check-out operators, care workers, food operatives, security guards, and bus drivers are just some of the occupations that earn below the average employee, some well below, and also experience a number of negative working conditions, particularly regarding anti-social work hours.

Women and people from ethnic minority backgrounds are over represented in jobs with more negative job quality indicators. For example, 84 per cent of care workers and home carers were women, while 49 per cent of them worked weekends and 61 per cent regularly worked evenings or nights.

The majority of primary school teachers, nursery assistants and retail cashiers were also women. Ethnic minority workers were over-represented in occupations such as security guards and medical practitioners.

This would suggest that pay is only one part of the discussion on how key workers are rewarded for the work they do moving on from the pandemic.