The cost of inflation for wellbeing

With inflation reaching record highs, the UK is currently experiencing a cost of living crisis. People perceive inflation as a major worry for the future, and we know that feeling secure and in control of your money is a key driver of wellbeing.

Our Senior Analyst Simona Tenaglia takes us through inflation’s impact on how we’re doing, and what can be done to help.

Inflation is a big concern for people

According to the latest Office for National Statistics data, around 9 in 10 (93%) adults reported their cost of living had increased since last year. Opinion Life Survey data for April to May 2022 shows that around three in four adults (77%) feel very or somewhat worried about rising prices. Worries include not being able to cope with increases in costs for energy, food or transport.

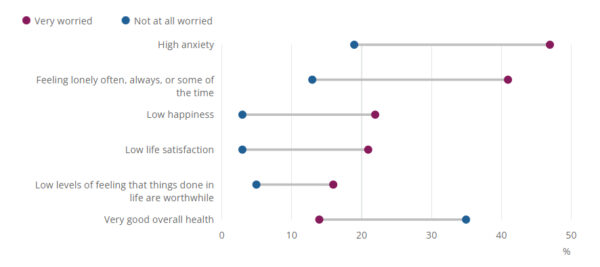

Those who reported feeling very worried also reported worse scores on anxiety, when compared with those who said they were not at all worried (figure 1):

Figure 1: Proportion of adults aged 16 years and over with low or high scores on measures of well-being, by those who felt not at all worried or very worried about the rising costs of living, Great Britain, 27 April to 22 May 2022 (Source: Office for National Statistics – Opinions and Lifestyle Survey)

Though these findings do not provide evidence on causality, as inflation usually happens when other negative things are happening, it is clear that worries about inflation are correlated with higher levels of anxiety.

Those most concerned and with higher level of anxiety are:

- women;

- people aged between 30 and 49;

- people with disabilities;

To cope with rising prices, the most commonly reported lifestyle changes were:

- spending less on non-essentials (57%, around 26 million people);

- using less gas and electricity at home (51%, around 24 million people);

- cutting back on non-essential journeys in their vehicle (42%, around 19 million people).

What is inflation?

Inflation is the rate at which prices are increasing on average. There are a number of ways of calculating it, but the most commonly used in the UK is the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Inflation is calculated by checking the price of a ‘basket of goods’ which reflects typical household expenditure – what we buy, and how much of it. It is calculated by the Office for National Statistics, who send out agents to find out the costs of items in the basket of goods around the country on a regular basis.

The price level can be viewed as a measure of money’s value. Unless income rises with prices, inflation decreases the purchasing power of our earned pounds. You can buy fewer goods and services, which means money has a lower value.

Even when wages adjust with inflation, we can still be made worse off objectively overall. This could be due to:

- “menu costs” – the additional business costs incurred from changing prices such as reprinting and updating websites;

- changes in tax;

- “shoe leather costs” – the costs associated with ‘shopping around’ more due to price volatility and the fact that not everybody buys the same things.

As the prices of energy and food are rising more quickly, some people – particularly those on low incomes, who cannot readily change their consumption patterns – might find themselves experiencing higher inflation. This is because they spend a higher proportion of their income on these essential resources.

What we know about inflation and subjective wellbeing

Research by Dolan, Peasgood and White (2008) has indicated that inflation is negatively related to subjective wellbeing. Similarly, Di Tella, MacCulloch, Oswald (2001), found that when inflation rates go up in Africa, Europe, Latin America and the US, people in those countries report lower levels of life satisfaction on average. They also found this negative relationship to be true for unemployment and life satisfaction.

Prof. Joseph Sirgy suggests that these effects may be explained by the bottom-up spillover theory of life satisfaction. This states that life experiences influence overall subjective wellbeing through a knock-on effect. In the case of inflation, price increases generate negative feelings. These feelings may play a significant role in a person’s dissatisfaction within their financial life. In turn, dissatisfaction with financial life contributes to dissatisfaction with life overall.

Financial stress, and its knock-on effects for mental health, relationship breakdown and physical health, can have severe consequences for individuals, organisations and communities.

Do economists think differently?

Nobel Prize Winner Robert Shiller conducted a questionnaire survey to explore how people in the US think about inflation and its outcomes. As part of this work, he investigated whether knowledge of economics can change individual attitudes.

Findings indicated a difference in perception of inflation and its impact between “lay” people and economists:

- 77% of “lay” people agreed with a statement that inflation influences purchasing power by making people poorer, compared with 12% of economists;

- 66% of “lay” people reported feeling a sense of unease and uncertainty over their income when listening to predictors about rise in cost of living, compared with 5% of economists;

- 52% of “lay” people said preventing high inflation should be a high priority for government, compared with 18% of economists;

- 49% of “lay” people reported they would feel more satisfied with their jobs if their salary increased, even if prices increased, compared with 8% of economists.

While economists assume that wages go up in line with prices, at least in the medium term, the general public assume they don’t. Rather than proving the general public are wrong and economists are right, the survey findings show that economists think differently about the effects of inflation, particularly the long-term impacts. For example, a classical economic approach would say that if price rises are causing purchasing power to decline, then it’s not inflation, it’s a recession.

The findings may also be partially explained by social-economic factors, such as a disparity in income of the general public vs. economists, giving a stronger buffer against financial uncertainty.

What can be done?

By policymakers

The mandate of the Bank of England is to keep inflation within boundaries through monetary policy. Similarly, the UK Government is seeking to control inflation through national fiscal policies. The Growth Plan 2022 makes growth the main economic mission by promoting investment, and cutting and simplifying taxes. The government is also seeking to address high energy bills through the new Energy Price Guarantee and Help to Heat funding, and has committed to a new six-month Energy Bill Relief Scheme for businesses and other non-domestic energy users.

While inflation is causing an increase in anxiety, we know that unemployment also plays a strong role in subjective wellbeing. It can have a greater impact on life satisfaction and happiness than inflation. As such, employment should be addressed as a priority, alongside managing inflation.

Something to be considered is the Phillips curve, which suggests an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment. This indicates a possible short-term trade-off and that policy makers must choose between prioritising one or the other. However there is debate amongst economists about whether this is the case.

By employers and practitioners

The Money and Pensions service outlines five key areas of UK financial wellbeing:

- Receiving a meaningful financial education.

- Saving regularly.

- Using credit for everyday essentials.

- Accessing debt advice.

- Planning for and in later life.

Employers are uniquely positioned to deliver financial guidance across some of these key areas, particularly at the transitional times in their employees lives, such as when they start work, become parents or retire, when employees are most likely to need help.

People who enjoy good financial wellbeing are more productive at work, so supporting them is mutually beneficial.

One possible action is to make it easier for employees to access financial education and guidance. Understanding mechanisms of inflation and wider financial wellbeing may help mitigate worry. Incorporating this as part of a broader organisational wellbeing programme is, according to the evidence, likely to be most effective for wellbeing and performance.

References

Blanchflower, D. G. (2007). Is unemployment more costly than inflation? Working Paper 13505, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R., & Oswald, A. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. American Economic Review, 91, 335–341.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R., & Oswald, A. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 809–827.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. P. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 94–122.

Hongo, D. O., Li, F., Ssali, M. W., Nyaranga, M. S., Musamba, Z. M., & Lusaka, B. N. (2020). Inflation, unemployment and subjective wellbeing: nonlinear and asymmetric influences of economic growth. National Accounting Review, 2(1), 1-25.

Shiller R. J. (1997), Why Do People Dislike Inflation? In (Eds) Romer, C. D., Romer, D. H. Reducing Inflation: motivation and strategy. (13-70). University of Chicago Press.

Sirgy, M. J. (2021). The psychology of quality of life: Wellbeing and positive mental health. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Veenhoven, R., Ehrhardt, J., Ho, M. S. D., & de Vries, A. (1993). Happiness in nations: Subjective appreciation of life in 56 nations 1946–1992. Erasmus University Rotterdam.