The individual, place, and wellbeing – a network analysis

The Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) is a popular and well-used measurement of mental wellbeing. It is used in national and regional wellbeing outcomes frameworks and extensively across civil society and health sectors. The What Works Centre for Wellbeing is currently looking at the extent of its use since it started in 2007 and what evaluations using the measures found.

At an individual level personal wellbeing is ‘feeling good and functioning well’ and is affected by individual and external factors. What matters most to our overall mental wellbeing is our self perception:

- Feeling good about one’s self and feeling confident.

- Positive mood – feeling cheerful.

These are closely influenced in both men and women through feeling close to others. For men, feeling useful and thinking clearly are also closely related to feelings of confidence.

Community level wellbeing is ‘how we’re doing’ as a community made up of the overall wellbeing of the individuals living there and its distribution, the relationships between people and the external conditions in the place.

The research highlighted in this blog looks at how these inter-relate using network analysis of (S)WEWMBS using data collected from residents of neighbourhoods in the North West Coast of England in 2015-16.

This wellbeing network analysis from the Communities of Place Evidence Programme, highlights what matters for wellbeing using these measures and the complex relationships that exist between individual, community and place – as one of the researchers Eoin McElroy outlines in this blog.

We already know, from ONS data and from previous publications that personal wellbeing varies by place and that the individual questions that make up ONS’s personal wellbeing scale are also place-based.

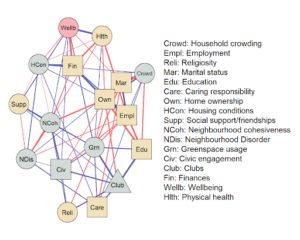

In our recently published study, which draws on survey data from over 4,000 individuals from the North-West of England, we used state-of-the art statistics (network psychometrics) to explore how subjective feelings of wellbeing were related to individual, community, and place characteristics. We found that all of these factors formed a complex, highly connected network (see Figure 1).

In other words, subjective wellbeing was connected either directly or indirectly to all of the individual, place and community factors we measured.

Blue lines = positive relationship. Red edge = negative relationship. Grey nodes = place characteristics. Yellow nodes = individual characteristics

What we found

We found that individual characteristics are the strongest predictors of subjective mental wellbeing. In this analysis, subjective financial difficulty and physical health had the strongest connections with overall wellbeing, represented in the composite Short WEMWBS score:

- Strongest was a negative association between perceived financial difficulty and the item ‘I’ve been feeling relaxed’.

- Social support and ‘I’ve been feeling close to other people’ was also notably strong. At a national level we know that having someone to rely on in times of trouble is the second biggest explainer of wellbeing between high and low wellbeing countries.

Place based characteristics also matter even after controlling for established individual-level correlates:

- Using local greenspace is positively associated with ‘I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future’ and ‘I’ve been feeling close to other people’.

- ‘Feeling useful’ and was more strongly associated with wellbeing than any other place-based/neighbourhood factor. Showing that it is not availability of local open space assets per se that is the issue in relation to wellbeing, but rather the use of those assets that is the important determinant.

- Civic agency is positively associated with the item ‘I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future’.

- Neighbourhood cohesion is positively associated with the item ‘I’ve been feeling close to other people’ and negatively associated with housing disrepair.

Implications

- Areas characterised by a lack of accessible open space, civic disengagement, a lack of neighbourhood cohesion, and housing disrepair seem to be at particular risk of low wellbeing.

- Accessibility, stewardship and management of local public spaces merits attention at policy level, if the ambition is to improve subjective wellbeing at scale.

Overall, these findings suggest that wellbeing is a complex network of mutually reinforcing elements. Implications for policy-makers will be to consider factors from multiple domains, and indeed complex interactions between these factors, when developing strategies to improve the wellbeing of the population. Governance measures to avoid and/ or address poor housing conditions are also critical for sustainable wellbeing improvements.

What you can do

Read further evidence of what works in this area for:

- Community Business

- Joint Decision Making

- Early stage ‘what works’ evidence on green spaces and social connection

- Outdoor recreation and the family

What next

All these things are interconnected and our work to understand this is ongoing. We are working with Spirit of 2012, the Centre for Ageing Better and researchers at Birmingham and Warwick Universities to develop a model that articulates the relationships between individual and community wellbeing and how this relationship is different for different people and in different places.

We are also looking at geo-spatial variations in wellbeing and loneliness for young people with Dr Emily Long and team at Glasgow University.