World Happiness Report 2018: migration, wellbeing and happiness

Edited 20/03/18 to add: The UK analysis in this report is based on data from the Gallup poll and the Office of National Statistics Annual Population Survey: Estimates of personal well-being broken down by country of birth and years since arrival to the UK, three years ending December 2016 At present, both of these surveys do not include ‘non-household populations’ (e.g. those in care homes, educational establishments, prisons, the homeless) . This means that there could be individuals with very low wellbeing who are not captured in the sampling frame and therefore not represented in these average figures.

Today is the launch of the World Happiness Report 2018, which focuses on migration. In today’s guest blog John Helliwell, report co-author and world leading happiness economist, shares the findings.

The Nordic countries did very well in the Winter Olympics, as usual, and now, a month later, they do even better in the world happiness rankings. The rankings of country happiness are based this year on the pooled results from Gallup World Poll surveys from 2005-2017, and show both change and stability. Although Finland is the new gold medalist, the top ten positions are held by the same countries as in the last two years, with some swapping of places

This year, for the first time, countries are ranked not just for the happiness of their overall populations (as measured by the average life satisfaction of their residents), but also by the happiness of their foreign-born populations, people who have been born in countries other than where they now live.

Figure 1. Percentage of population born outside the country

Immigrant happiness mirrors rest of population

Five of this report’s seven chapters deal primarily with migration. Perhaps the most striking finding of the whole report is that if we rank countries according to the happiness of their immigrant populations, the results are almost exactly the same as for the rest of the population. The immigrant happiness rankings are based on the full span of Gallup data from 2005 to 2017, which looks at 117 countries with over 100 immigrant respondents. Finland picks up a second gold medal here, as home to the world’s happiest immigrants.

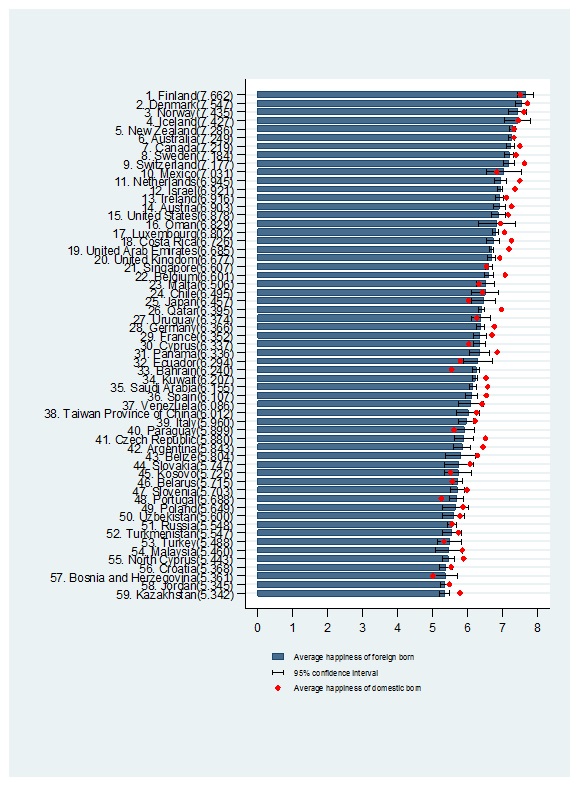

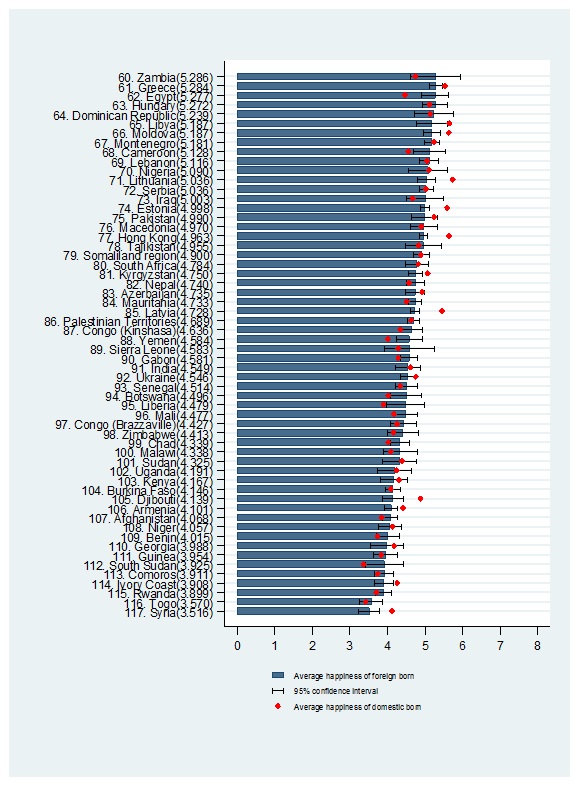

The chart (Figure 2) below ranks countries by the average score of their foreign-born respondents in all of the Gallup World Polls between 2005 and 2017. The red dots show the corresponding average life evaluations for domestic-born respondents. For domestic-born respondents, the sample sizes are so large that the estimates are very precise; this is why there are no error bars showing our confidence in the findings. Because the foreign-born data is from a smaller pool, the error bars show the 95% confidence regions, which are much more precise for those countries with larger migrant shares.

Figure 2: Happiness Ranking for the Foreign-Born, 2005-2017, 117 countries

But wellbeing in country of origin plays a role

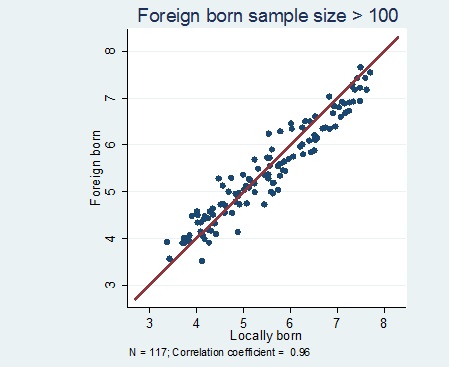

For the 117 countries with more than 100 foreign-born respondents, the cross-country correlation between the average life evaluations of the foreign-born and domestica-born respondents is very high, 0.96, as shown in the graph below.

Figure 3: Comparing the happiness of immigrants and those born locally, for 117 countries

The closeness of the immigrant and local-born rankings suggests that immigrant happiness depends predominantly on the quality of life where people live. There is, however, a footprint effect: happiness levels in the countries of origin are a factor, with immigrant happiness being slightly below locally-born happiness where the destination country is happier, and vice versa.

Immigrant wellbeing changes to match UK-born population

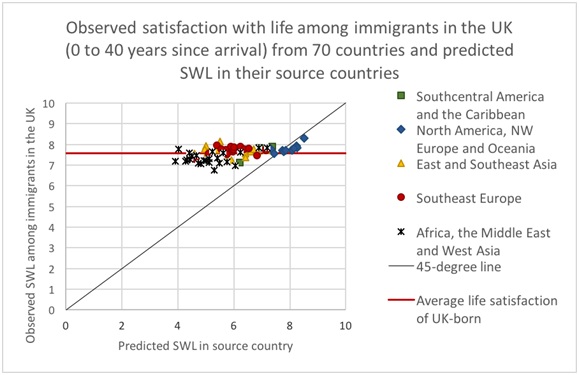

This pattern of convergence of migrant happiness to the levels of the locally born becomes much more convincing if it can be shown to apply to migrants coming from many source countries to a single destination country. To do this requires very large wellbeing surveys, with samples many times larger than available in the Gallup World Poll. An analysis of UK wellbeing data, from the Office For National Statistics, as part of the World Happiness Report provides estimates of the life satisfaction of immigrants to the United Kingdom from 70 different countries, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Life Satisfaction among immigrants to the UK from 70 countries

For immigrants to the UK, their happiness moves substantially, mostly from below but sometimes from above, towards that of the rest of the population. UK immigrants come from countries with an estimated average life satisfaction of 6.24 on a 0 to 10 scale, while immigrants from those same 70 countries now living in the UK have average life satisfaction of 7.57. This shows widespread convergence towards the overall UK average life satisfaction of 7.65.

Happiness is not fixed

Happiness can change, and does change, according to the quality of the society in which people live. Immigrant happiness, like that of the locally-born population depends on a range of features of the social fabric, extending far beyond the higher incomes traditionally thought to inspire and reward migration. The countries with the happiest immigrants are not the richest countries, but instead the countries with a more balanced set of social and institutional supports for better lives.

The world’s happiest countries have, over many decades, developed levels of institutional and interpersonal trust, connections, and co-operation that allow the majority of residents to live satisfying lives.

To learn and apply the lessons that underlie their happiness it is important to remember that happiness is not something inherently in short supply, like gold, inciting rushes to find, and much conflict over ownership. Happiness, unlike gold, can be created for all, and can be shared without being scarce for those who give. It even grows as it is shared.