Civil Service wellbeing over time: exploring data from the Civil Service People Survey 2019-22

Downloads

About the paper

We are least satisfied with our lives between the ages of 23 and 68, the age many people are in employment. Being employed is a particularly important short and long term driver of life satisfaction. Beyond having a job or not, the quality of our job and how satisfied we are with it is important for our overall wellbeing.

A workforce’s wellbeing is an important concern for employers, as unhappy and unmotivated employees are likely to experience greater absence, turnover, and lower productivity than one that has higher wellbeing.

Collecting and analysing workplace wellbeing data provides an insight into how staff wellbeing is affected over time across organisations, type of work and in the context of the wider world. Measurement of job quality is still unclear but Job Satisfaction has been improving in the UK over the long term since 2015/16.

Through the annual Civil Service People Survey, the UK government has collected wellbeing data in the civil service with results available from 2014. This provides valuable insight into employee wellbeing in different government organisations before, during and through recovery from the pandemic.

In this short paper, we build on our previous analysis to further consider:

- How civil service wellbeing has changed over the pandemic, and how it has changed over the longer term.

- How the civil service has continued its recovery from the deleterious effects of the Coronavirus pandemic.

- How loneliness and stress within the civil service are changing over time.

Changes through the pandemic

Our first analysis looks at how wellbeing has changed over the last few years. The pandemic is likely to have had a major impact on subjective wellbeing of the civil service, as it has across the nation as a whole. We update our previous analysis, conducted last year, by including an additional year of data to see whether the service’s recovery has continued.

This dataset is hugely valuable not just for understanding wellbeing in the civil service, but also across the country – not necessarily because civil service wellbeing is representative per se, but because the response rate for the civil service people survey is high, compared to many other surveys.

To investigate both the overall trends and to continue our analysis of civil service recovery from the pandemic, we conduct a basic linear regression analysis, in which departmental wellbeing is regressed on a pre-pandemic trend, and in which 2020, 2021 and 2022 appear separately as binary indicators for those years.

Through this analysis, we are able to compare the average proportion of people scoring highly on the four wellbeing questions asked in the civil service people survey. For Life Satisfaction, Worthwhile and Happiness indicators, a higher score is better, while for anxiety, a higher score is worse. The results of a straightforward OLS regression made on these data are presented in table 1.

Table 1: Changes in wellbeing among civil servants over time (pre, peri and post pandemic)

Life Satisfaction Worthwhile Happiness Anxiety

2022 -0.039*** -0.020*** -0.022*** 0.144***

2021 -0.031*** -0.017* -0.018* 0.092***

2020 -0.082*** -0.045*** -0.057*** 0.149***

Trend (pre-pandemic, 2014-2019) 0.005*** 0.002* 0.002* -0.042***

Regression Constant 0.636 0.698 0.613 0.589

N 936 936 936 936

Notes: * = p<0.05 **= p<0.01 ***= p<0.001

Data used are drawn from HMG departmental breakdowns of civil service people surveys from 2014-2021. Huber-White Robust standard errors in parentheses.

What are p-values?

P values denote whether the difference between two numbers is ‘statistically significant’. They relate to the confidence with which we are able to reject the null hypothesis of no effect. In the regression results shown above, this denotes whether the value attached to a variable (for example, the trend) is significantly different from zero. If the difference is statistically significant, for example at the p<0.05 level, denoted by a single *, then we are 95% confident that the number is greater than 0.

In the case of the trend in life satisfaction, we see that life satisfaction is rising over time. The point estimate is 0.005, which is statistically significant. This does not tell us how likely 0.005 is to be the correct value – instead, it only confirms that we are confident that the trend is in an upward direction.

The pre-pandemic trend for all four outcomes was encouraging:

- The proportion of civil servants with high life satisfaction rose by half a percentage point per year.

- The proportion with high happiness and worthwhileness scores rose by 0.2% points per year.

- Anxiety fell on average by 4.2% points.

These trends are slower than we observe in the general population (see for example our recent paper on wellbeing trends across local authorities), but are nonetheless encouraging.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the pandemic has overturned these trends. In 2020:

- Life satisfaction fell by 8.2% points, overturning the equivalent of 16 years at pre-pandemic trends.

- Worthwhileness and Happiness experienced smaller percentage points drops (4.5% point and 5.7% point respectively), but due to the slower pre-pandemic growth, this is the equivalent of more than 20 years progress for those measures.

- Anxiety experienced the largest change, rising by 14.2% points in 2020.

The 2020 People Survey was open 1 October 2020 to 3 November 2020.

The story since the pandemic year itself is mixed. Data for 2021 and 2022 were collected in between September and November of those years – 18 months and 30 months after the initial March 2020 lockdown.

In our analysis last year, we noted that while 2021 levels remained significantly lower than pre-pandemic, they had improved significantly since 2020, suggesting that the civil service’s wellbeing was on the path to recovery.

The 2022 data provide a less optimistic picture:

- For three of the wellbeing measures – Life Satisfaction, Worthwhileness and Happiness – levels have remained almost perfectly static between 2022 and 2021. These remain statistically significantly better than in 2020, but show no improvement since 2021.

- Anxiety, which showed slower recovery going into 2021, is getting closer to 2020 levels. The extent to which anxiety deviates from the general time trend has returned to pandemic levels, although things have improved slightly in overall levels.

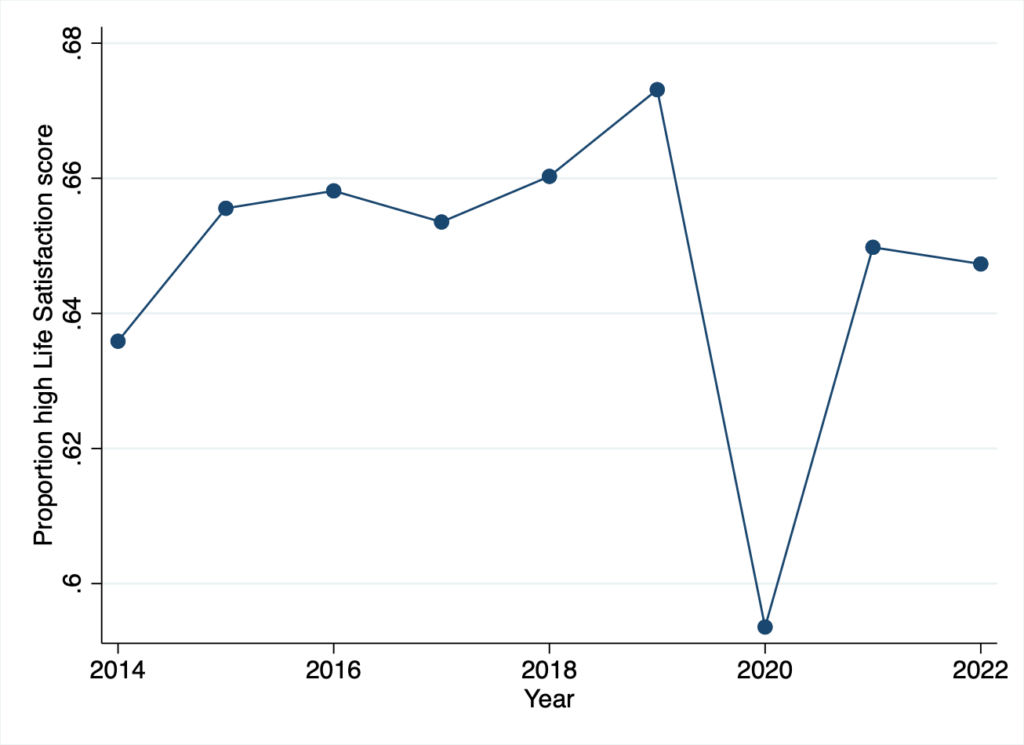

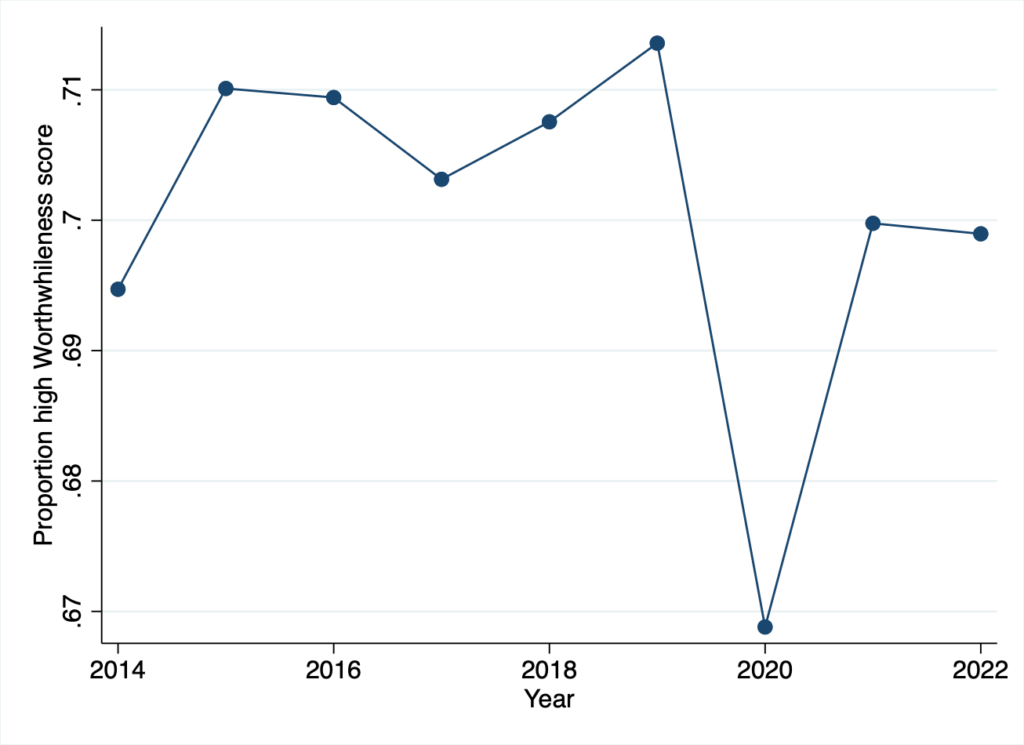

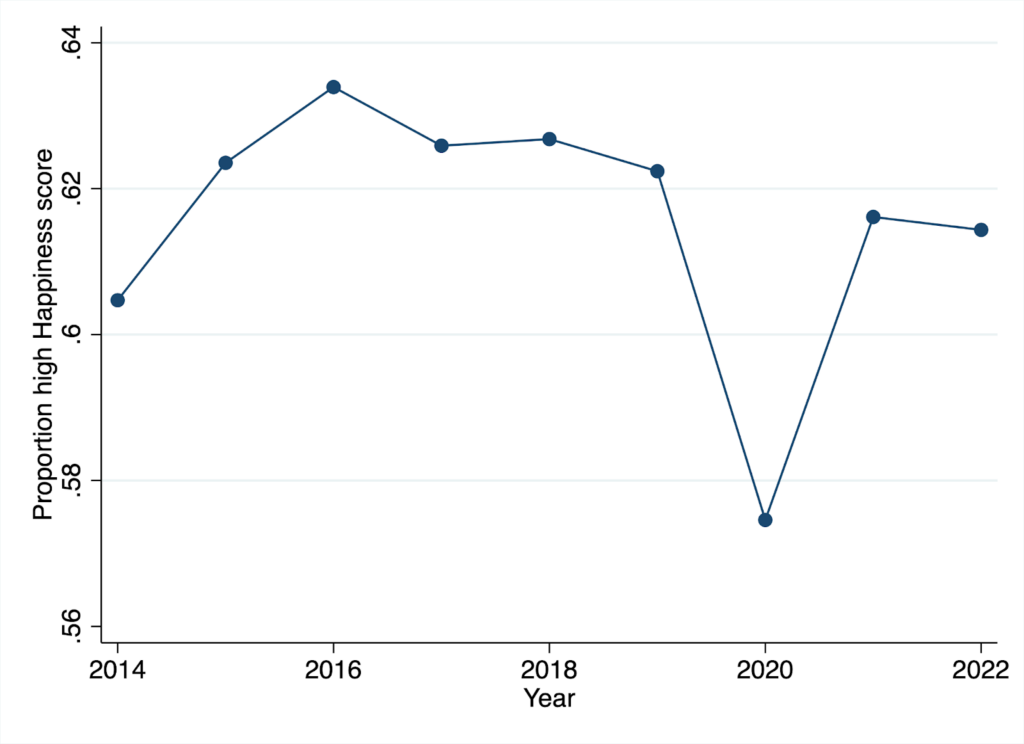

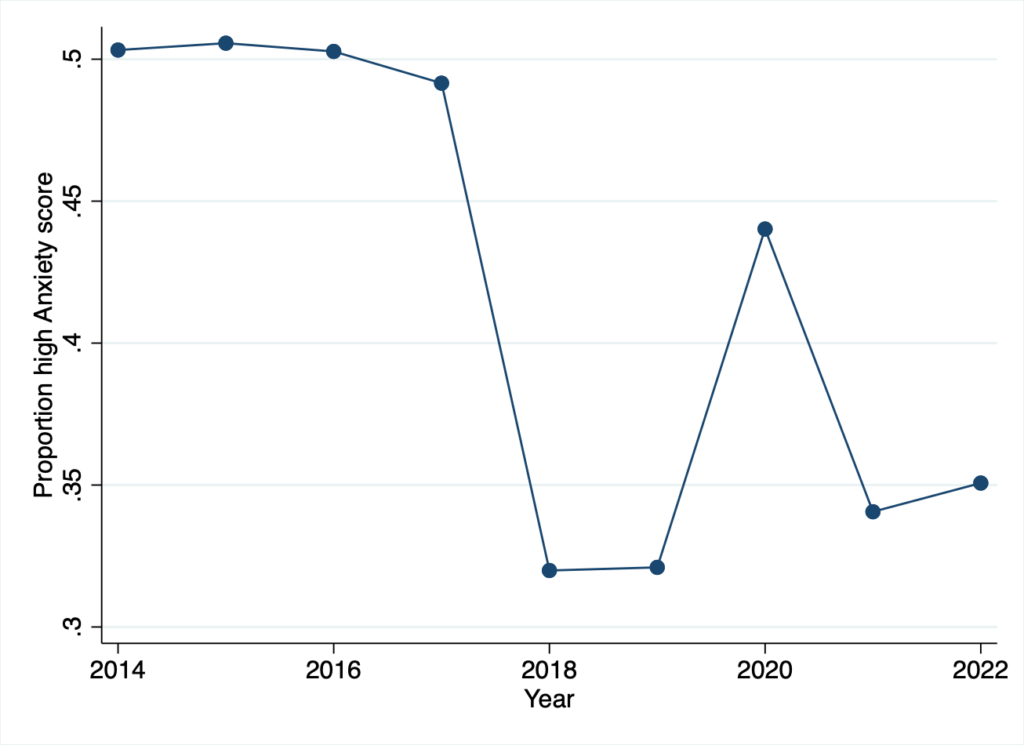

We can now look at these data graphically to help us to evaluate the changes compared to prior trends (figures 1-4). This panel data is not balanced – there are fewer departments’ data earlier in the time series, and some departments move in and out of measurement (one prominent example is the Test and Trace service, which for obvious reasons first appears in 2020). Figures 1 to 4 show averages across all departments reporting (without weighting for department size), from 2014-2022.

As with the regression results, there is a clear trend – things got substantially worse in 2020 – reaching their worst level on record for three of the four indicators. We see substantial average recovery in 2021, which stalls moving into 2022.

In the raw data, which does not control for the pre-existing time trend, the uptick in anxiety in 2022 seems smaller, suggesting that while things have gotten worse in the last twelve months, it is more pronounced relative to the anticipated time trend that existed pre-pandemic.

Figure 1: Changes in proportion of civil servants with high life satisfaction over time

Figure 2: Changes in proportion of civil servants with high worthwhile over time

Figure 3: Changes in proportion of civil servants with high happiness over time

Figure 4: Changes in proportion of civil servants with high anxiety over time

Were changes between 2021 and 2022 uniform?

The civil service has on average experienced flat wellbeing over the course of the last twelve months. As with our previous report, it is helpful to consider whether these changes are uniform across the civil service, and whether some departments have had a better year than others.

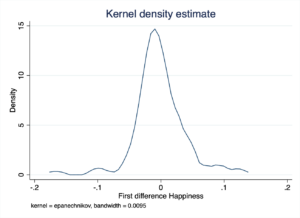

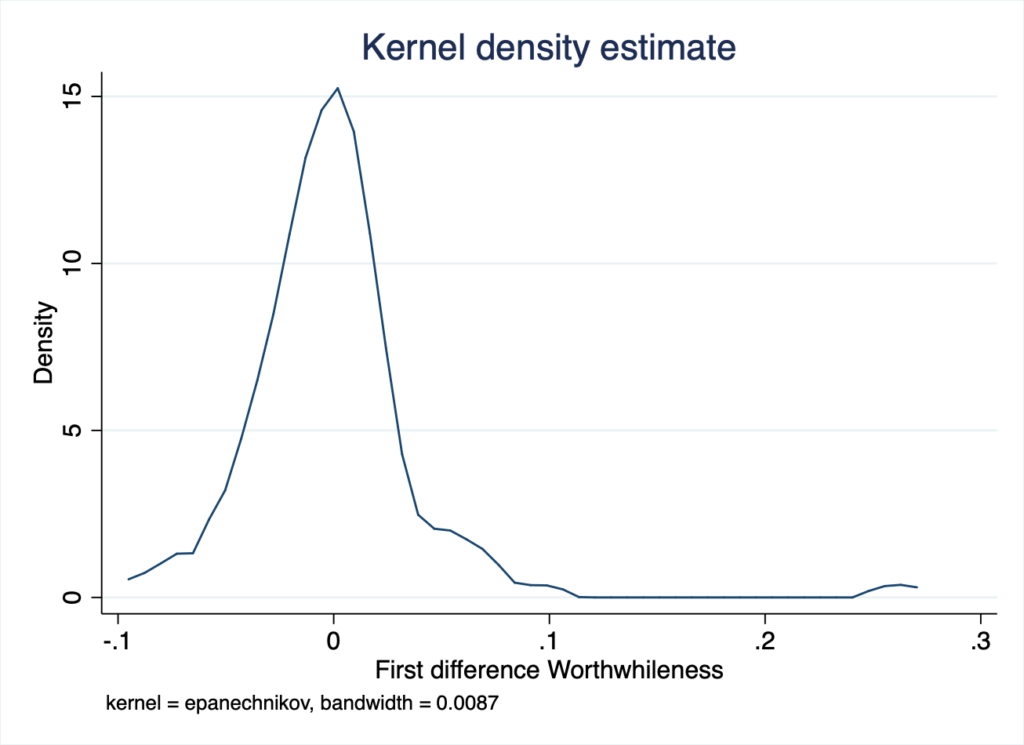

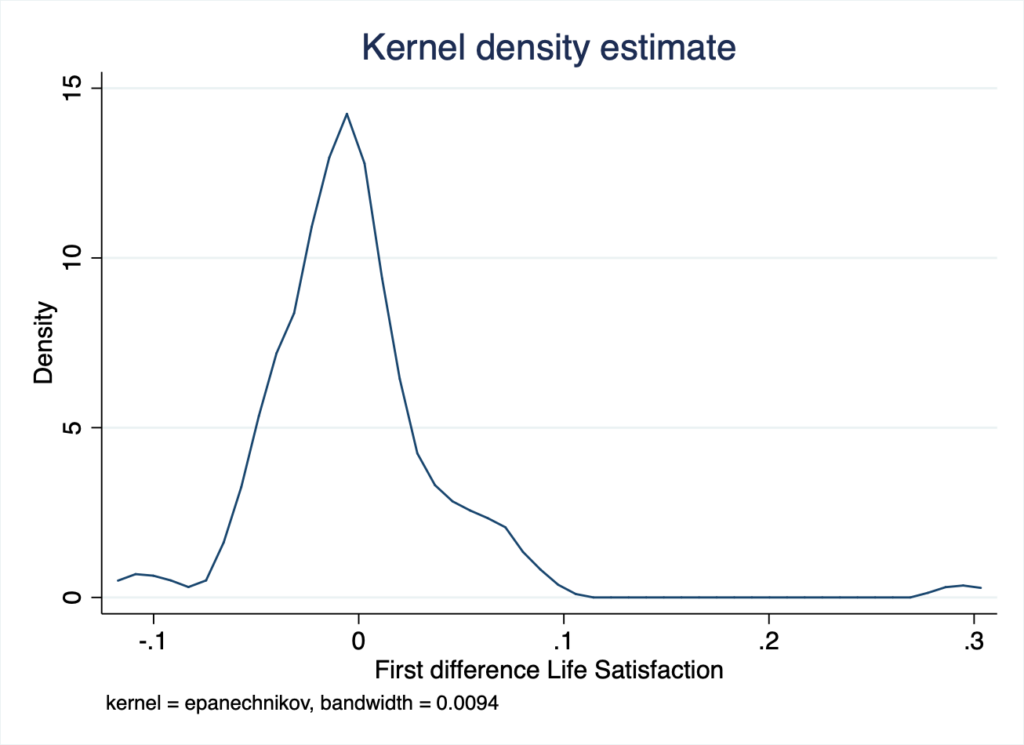

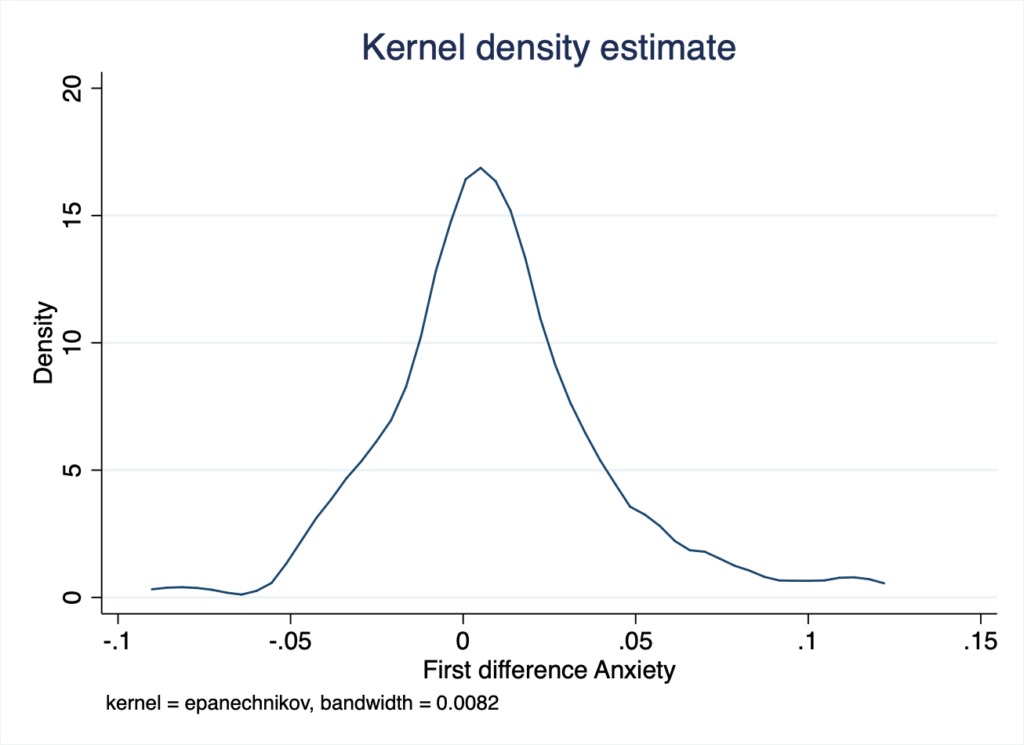

To do this, we establish an unbalanced panel within our data, and look at changes within the same cluster over time. We then take the first difference of each of our measures between 2021 and 2022, which is how much the scores change for these four measures in that organisation over that twelve months. These are then mapped in kernel density plots, which can be found below (figure 5).

The central tendency is clearly close to 0 change in the last twelve months. However, there is heterogeneity across departments. These distributions are tighter than those seen in the comparison between 2020 and 2021, suggesting that the experience has been more homogeneous across the civil service this year than the previous one.

A kernel density plot maps the distribution of a variable. For any given value on the variable (shown on the x axis), the height of the graph shows the density of that distribution at that point. The values on the y axis aren’t straightforward to interpret, but we can say that;

There are lots of people around values of the variable where the y axis value is high, and fewer people around variables of the y axis are low. Where the y axis is twice as high at some value than it is around some other value, that means there’s about twice as many people with the first value than the second.

The area under the entire kernel density plot sums to 1, and so we can derive the proportion of people with values of the variables between x1 and x2, as the integrand of the curve between x1 and x2 – which is what gives rise to the slightly confusing values on the y axis.

Fig 5. Kernel density plots for Life Satisfaction, Worthwhile, Happiness and Anxiety

As these graphs show, different measures have different levels of spread and different distributions, as well as different levels that we have seen in previous sections. These graphs are not normally distributed, and in particular they generally display some degree of skewness (the majority of values lie to one side of the mean), and kurtosis (there are more organisations with both extremely high and extremely low changes year-on-year than the normal distribution. Only the results of question Anxiety, do not exhibit significant levels of skewness and kurtosis compared to the normal distribution.

Another, more binary indicator of experiences across departments is to consider how many organisations have negative first differences on all of the measures, and how many have positive first differences on all of the measures. This would mean that wellbeing is either worsening, or improving, in these departments on all of these measures compared to the previous year.

During the pandemic year, 90 out of 105 organisations had negative first differences across all four questions – meaning that things got worse on all four measures – while none had positive first differences across all four measures.

This year, 17 organisations had positive changes in all four scores – improving wellbeing on all of the measures (listed below), while 33 had negative changes across all four scores.

- Competition and markets authority

- Criminal Injuries Compensation authority

- DSTL

- Education Scotland

- Food Standards Agency

- Government Property Agency

- HM Prison Service

- Met Office

- Ministry of Justice

- National Savings and Investments

- Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem)

- Ofsted

- Scottish Government

- Scottish Housing Regulator

- Student Awards Agency Scotland

- Vehicle Certification Agency

- Water Regulation Services Authority

This list is notable in that it contains several organisations in Scotland, which we noted in our previous paper were disproportionately negatively affected by the pandemic, suggesting faster recovery in places worst affected. Perhaps more strikingly, only one of the 17 is a central government department (the Ministry of Justice), while the remainder are arms length bodies, regulators and similar.

Central departments

In previous years, central government departments have sat mostly in the middle of the distribution of wellbeing. Many of these departments have experienced systematic drops in wellbeing in 2021-2022.

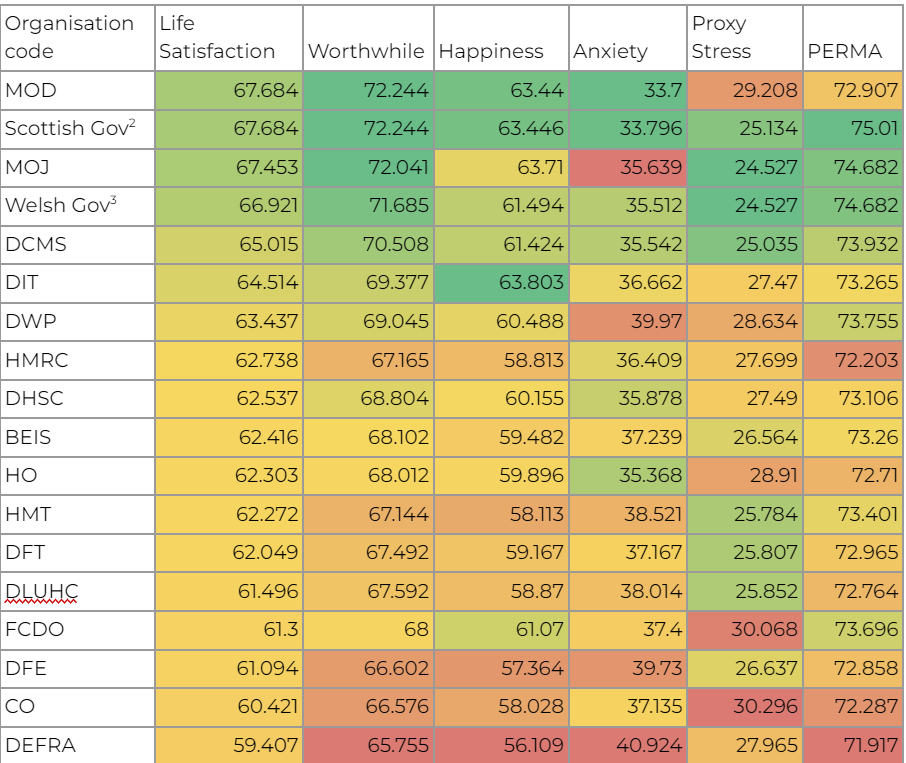

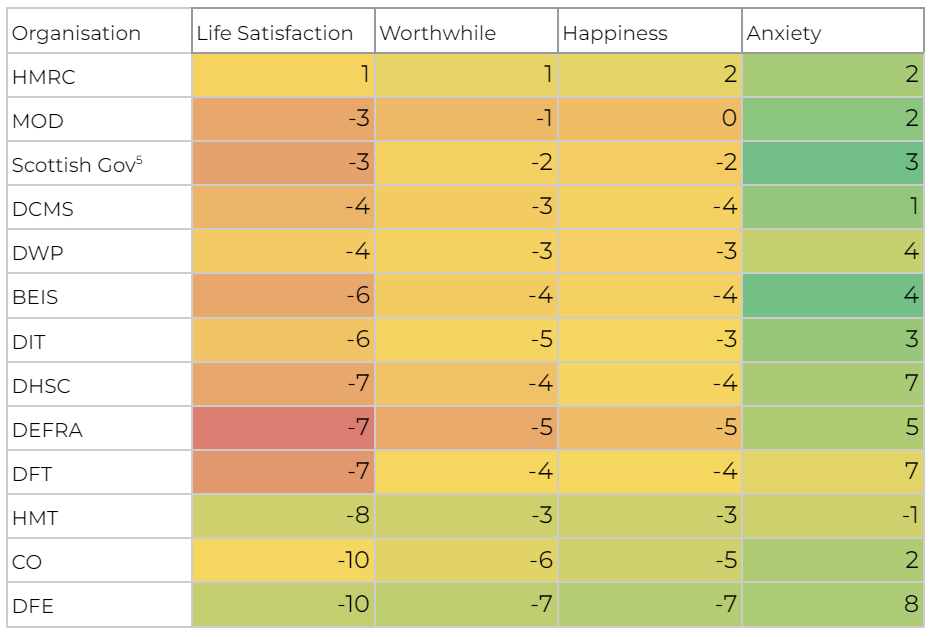

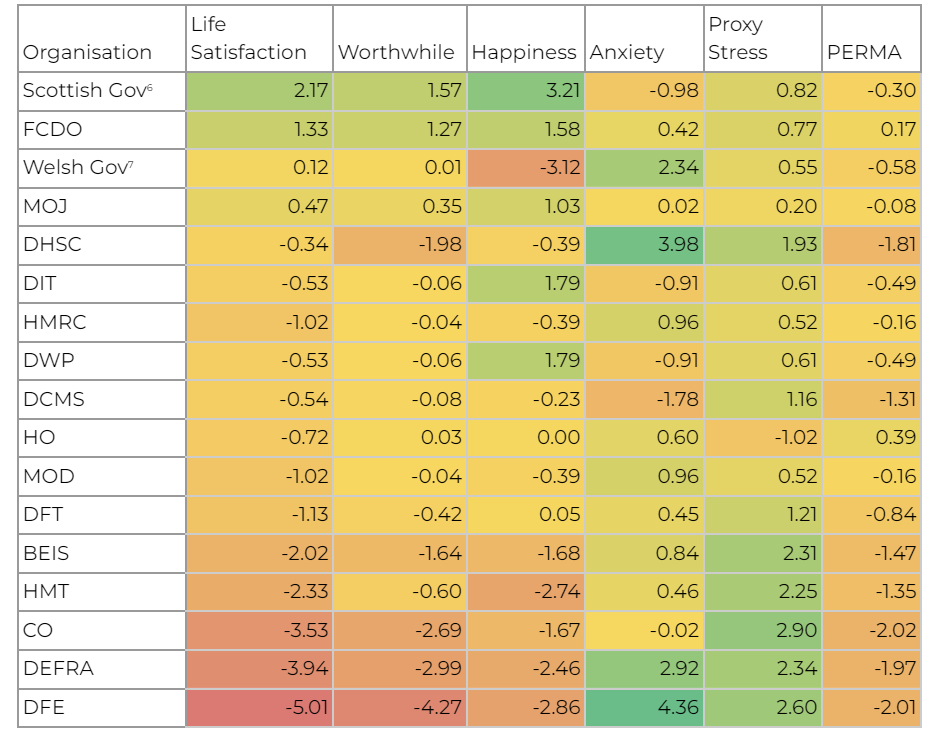

To zoom in on these central departments, we show below three tables. The first of these (table 2) shows levels of wellbeing in 2022. Table 3 shows changes from 2019-2022 (from before the pandemic to now) and table 4 shows changes from 2021-2022 (changes in the last year).

Proxy stress is a combined measure of stress (good/bad) in the organisation based on the HSE management standards. PERMA is a combined measure of the protective aspects of wellbeing based on the PERMA model of flourishing.

Values within tables below are colour coded with green values representing the more positive end of the observed distribution and red the more negative end.

Amalgamated scores from multiple departments are presented where data are available.

Table 2: Percentage of Civil Service staff with high wellbeing 2022

Table 3: Changes in civil service wellbeing pre and post pandemic 2019-2022

Table 3 shows the changes in wellbeing experienced by departments between the pre-pandemic period of 2019 (for which data were collected in September-November 2019), and the most recent data from 2022. Only one department – HMRC – has recovered to their pre-pandemic levels on any of the measures, although HMRC still has higher anxiety than pre-pandemic.

Note that Ministry of Justice (MOJ) is omitted from this table due to inconsistencies over time in how it is defined either including or excluding arms length bodies, and that the Welsh Government is omitted due to not having data in 2019.

Table 4: Changes in civil service wellbeing 2021-2022

The organisations towards the top of table 4 experienced the biggest increases in wellbeing or reductions in anxiety between 2021 and 2022.

Conclusions

In this paper we have looked at the wellbeing of civil servants across central government departments, as well as regulators, arms length bodies, and the Scottish and Welsh governments. This builds on our previous report, published in July 2022, with the addition of another year of data.

Last year our report contained substantial cause for optimism. The direction of travel across the civil service pre-pandemic had been generally upwards, and although the pandemic had a substantial negative effect on wellbeing, around half of this drop had been recovered by 2021. At that time, this gave us cause for positivity around the wellbeing of civil servants into the future, with what trend data we had suggesting that the service could be fully ‘recovered’ from the wellbeing effects of Covid by 2022.

In 2022, we see that this is not the case, and that wellbeing of civil servants has stalled. As with previous years, the pattern is not uniform across the public service, although the distribution of year on year changes is narrower this year than last year, suggesting a more homogenous experience across the civil service.

Central government departments have had a particularly bad year, with more than a third experiencing drops in wellbeing across all four measures. Of all the central government departments for which data are available, only HMRC has recovered its wellbeing to pre-pandemic levels (although it still retains higher anxiety than pre-pandemic).

Across the wider service, no organisations have fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels across the four wellbeing measures, with every organisation having experienced a rise in anxiety since 2019, and 21 organisations having experienced positive change in each of the other three measures since that time.

Suggested citation

Sanders, M., 2023. Civil Service wellbeing over time: exploring Civil Service People Survey data 2019-22 [online] What Works Centre for Wellbeing. Available at: https://whatworkswellbeing.org/resources/civil-service-wellbeing-over-time/ [Accessed dd month yy].

Explore more

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]