Creative pathways to personal wellbeing

Downloads

The quick read

We have brought together evidence on how and why creativity supports wellbeing.

The evidence shows:

- Creative activities can lead to a range of wellbeing outcomes.

- Pathways to wellbeing are both personal and relational.

- The importance of key factors including: skilled facilitators, inclusive and safe environments, autonomy and choice, and curiosity, immersion and distraction.

- A risk of negative outcomes if activities are not designed with key factors in mind.

This briefing is based on a rapid scoping review conducted by Brunel University London, in partnership with the Social Purpose Lab at the University of the Arts: London.

Background

There is a wealth of evidence on the link between arts and cultural activities and personal wellbeing, but the reasons behind this relationship are less well understood.

Knowing ‘how’ and ‘why’ creative activities support wellbeing can help:

- pinpoint the essential ingredients in effective interventions;

- draw out aspects which can stop wellbeing outcomes from being achieved

For us ‘creativity’ describes the process through which people apply their knowledge, skill and intuition to imagine, conceive, express or make

something that wasn’t there before. (Arts Council England)

This means that when we searched for evidence, it wasn’t enough that studies looked at arts, music or dance activities. They had to also say something about the role of creativity in these activities.

What we did

To understand the contexts and mechanisms that link creativity with personal wellbeing outcomes we:

- conducted a rapid scoping review of existing evidence;

- developed a model for policy makers, practitioners and researchers to use in their work.

The rapid scoping review

We searched for studies written in English and published since 2003.

The studies looked at creative activities in the UK, Republic of Ireland, Lithuania, Germany, Spain, Netherlands, Hungary, Finland, Turkey, USA, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and Hong Kong.

We looked at 16,434 studies – 68 from call for evidence. After synthesis, we included 55 studies, and five systematic reviews.

Studies were conducted in a range of settings including:

- Community venues (one community-based intervention began in person and then moved online after two weeks)

- Universities or colleges

- Hospitals and medical schools

- A laboratory

- A prison and correctional facility

- An art centre

- A WhatsApp group

The creative activities varied widely, ranging from one-off sessions, to a series of workshops. Participants took part both in groups or on their own, and as part of both

facilitated and self-led activity.

Types included:

- Creative writing

- Theatre

- Making art

- Video-making

- Art therapy

- Clay handling

- Virtual reality art making

The people covered were:

- Mostly women, mostly white, and a range of ages.

- A wide range of other characteristics, specifically targeted by the interventions, such as those with mental illness or chronic health conditions, healthcare staff, and prisoners and probationers.

Many of the studies didn’t fully report the characteristics of participants.

What we found

Where you see the following symbols it indicates:

-

qualitative

-

quantitative

-

strongWe can be confident that the evidence can be used to inform decisions.

-

promisingWe have moderate confidence. Decision makers may wish to incorporate further information to inform decisions.

-

initialWe have low confidence. Decision makers may wish to incorporate further information to inform decisions.

| Wellbeing outcome | Activity |

|---|---|

| ⇧ Subjective wellbeing | Silk painting, WhatsApp facilitated daily creativity challenges, creative writing, video-making, art-making, mixed art-making and art-interpretation activity |

| ⇧ Quality of life | Video making, art therapy |

| ⇩ Anxiety, Depression, Stress | Art interpretation, mixed creative writing with boxing activity, creative writing, WhatsApp facilitated daily creativity challenges, clay handling, 2D and virtual reality art making |

| ⇧ Self-esteem, confidence | Theatre, visual arts |

| ⇧ Positive mood ⇩ Mood disturbance | Mixed visual arts workshops, colouring, 2D and virtual reality art making, clay handling |

| ⇩ Fear ⇔ Happiness, anger, sadness | Colouring |

| ⇧ Social connection | Mixed creative and performing arts workshops |

Qualitative data provided insight into the contexts that can support the achievement of wellbeing outcomes.

The evidence we found was:

- primarily from local small-scale interventions spanning the literary, performing and visual arts;

- designed and delivered in community spaces and places, including community and arts centres, gardens, day care venues and residential venues;

- for general and targeted populations: including the general public, older

people, students and employees, members of creative groups, people with mental or chronic health conditions, prisoners, veterans, and refugees.

Who benefited from creative activities?

Although many of the participants across the studies were from the general

public, some wellbeing outcomes were associated with specific population

groups:

- Quality of life and social connectedness for young people with diagnosed mental health conditions and serious mental illness

- Quality of life for patients with Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and breast cancer

- Mental wellbeing for healthcare professionals

- Isolation, depression and mental ill-health for older people

- Improved mood and reduced anxiety among young adults, pregnant

women and prisoners

This doesn’t mean that the same activities wouldn’t benefit other groups, just that the studies targeted these groups in this case.

Who is missing?

Overall, there were fewer men and fewer people from minority ethnic groups represented in the studies.

This may be for a number of reasons:

- Barriers to participation – some people may be less likely to think that

creative activities are for them, or may not think of themselves as creative. They may have fewer opportunities and more barriers to taking part, because of personal circumstances or unequal geographical provision. - Different terminology – some groups may be taking part in creative

activities but not describe them as such (for example through gardening,

cooking, repairing). Everyday creativity, which takes place across settings and populations, was not a focus for this study

Some population groups are less represented in the evidence.

Policy makers – commission activities which reach people who are less likely

to participate in creativity, including using large-scale national and mega events as opportunities to bring new audiences to creative participation. Evaluating inclusive activities will help refine the evidence of which pathways to wellbeing work for different people.

Practitioners – continue to reduce barriers to participation and target people

who may benefit from creative activities but who may not think it’s for them. Delivering creative activities in different settings (for example, workplaces, green spaces, sport and leisure clubs) may lead to wider participation.

Researchers – study activities aimed at specific population groups (for example men, minority ethnic groups) and in settings (for example workplaces) which are under-represented. This may mean looking at interventions not commonly described as ‘creative’ but which meet the definition used in this review. Across the evidence base we need better reporting of participants characteristics (including age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic background).

Qualitative data shed light on mechanisms that lead to wellbeing outcomes.

| Personal mechanisms | Relational mechanisms |

|---|---|

| Active engagement and participation in creativity, including through creative interpretation. | Environments that foster trust, respect and support for creative endeavours. |

| Autonomy and choice around creative practices and journeys. | Positive interactions and connection, with other creators, friends, family and the wider community. |

| Feeling empowered and challenged to create and reflect. Valuing personal creative journeys. | Including people in decision making and co-production. |

| Experimentation and curiosity including learning new creative skills, and experiencing unfamiliar practices and materials. | Safe and supportive environments for experimentation and learning. |

| Making something meaningful and original, and the opportunity for self-expression. | Exhibiting and performing creative work to peers and the community. |

| Psychological and social strategies for coping with negative emotions, trauma and ill health. | Teaching and learning creative skills, and supporting different creative journeys. |

| Stress-relief, distraction and escape from daily life and negative emotions. | Skilled facilitation of creative activities and journeys. |

Evidence showed that not everyone has access to creative activities and enabling

contexts due to:

- Geographic variation in provision

- A lack of cross-sector policies for creativity and wellbeing

- A reliance on voluntary organisational delivery

We also found the following negative effects for some participants:

- Feeling overwhelmed and frustrated by the creative process

- Negative feelings associated by a lack of skill or competence

- Feeling vulnerable to criticism

- Not feeling fully involved in the co-creation of activities or processes

These negative effects can be mitigated by ensuring that positive mechanisms are built into the design of activities.

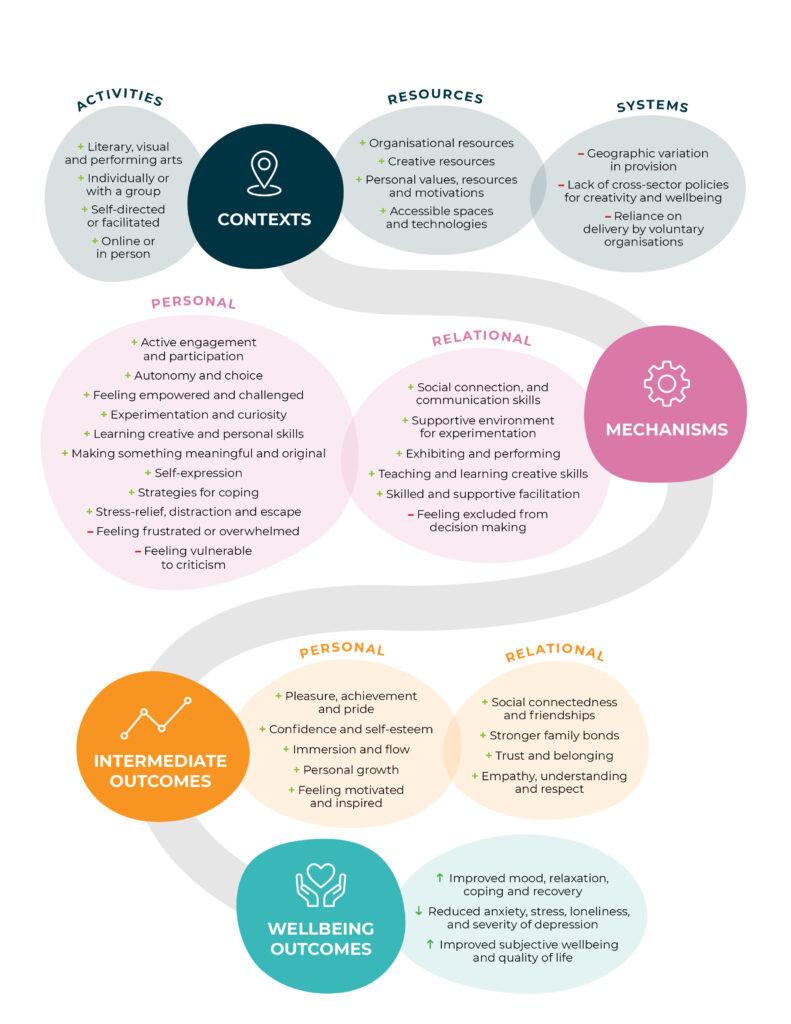

Creative pathways model

Based on existing evidence, the model sets out the creative contexts and mechanisms associated with wellbeing outcomes, so that we know what needs to be included in developing activities that work. Not all the elements will be relevant to all activities or people.

How to use this model

Context – the settings the activities took place in, the people involved, the type of activity, and the delivery circumstances. It also includes the wider social and

political environment for the interventions.

Mechanisms – the behaviours, motivations, social norms, relationships, culture, resources, underlying structures and politics that lead to an outcome being achieved.

Intermediate and wellbeing outcomes – the changes that occur as a result of the activities, often building on each other over the course of the intervention.

A green plus indicates activities, resources and mechanisms that facilitate effective outcomes. A red minus indicates context and mechanisms that act as barriers to effective activities. Green arrow indicate improvements in wellbeing outcomes.

When designing new creative activities, or revising existing ones, you can use this model to test your ideas to increase your chances of success:

- How does your context support wellbeing? Is it safe and supportive, are you reaching people who would not normally engage?

- Which mechanisms are involved in improving wellbeing through your activities, relational or personal, or both?

- Can you design in additional ways that support people’s wellbeing?

- Can participants shape the activities and co-create the programme?

- How will you enable individual learning journeys and curiosity?

- Do you have a plan for ensuring participants don’t feel frustrated or overwhelmed?

When evaluating existing projects, use this model to design your evaluation:

- Could you develop a theory of change based on the model to describe your own creative pathways to change?

- Can you use tested wellbeing measures to assess your impact and enhance the evidence base?

- Can your interviews and focus groups draw out the most important mechanisms of change?

- What do you want to learn that challenges or adds to this model?

No single pathway to wellbeing

Creative interventions are complex and likely to involve more than one pathway to wellbeing. The right mix of ingredients needs to be determined by the people taking part in the activity, their circumstances and motivations.

The evidence found that creative practice experts can support wellbeing by carefully calibrating the design of an intervention.

Case study: Left/Write//Hook

Left/Write//Hook supported women who had experienced childhood sexual abuse and trauma to “find a connection to their body, mind and spirit” through weekly writing and boxing workshops.

By considering the women’s feelings, circumstances, and motivations, the designed activities made use of a mix of contexts and mechanisms that enabled them to achieve improved wellbeing, reduced PTSD symptoms and reduced depression severity.

“Throughout the program, participants wrestle with the meanings and profundity of the effects of their abuse and trauma experiences through writing, and then physicalise these through boxing to release some of the confusion, shame and negativity that the writing and sharing may have brought up.”

Lyon, D., Owen, S., Osborne, M., Blake, K., & Andrades, B. (2020). Left/Write//Hook: A mixed method study of a writing and boxing workshop for survivors of childhood sexual abuse and trauma. International Journal of Wellbeing, 10(5). p.67.

Although all of the mechanisms and contexts are important, the pathways for

different people are less clear.

Policy makers – use the model to develop programmes which focus less on specific interventions, and more on the contexts and mechanisms that are needed for wellbeing. Support practitioners to engage with the evidence base to test the most important mechanisms for their target populations.

Practitioners – use the model to design and learn from their activities, identifying which mechanisms are most important in their contexts and for their participants.

Researchers – use model as a framework to design evaluations and studies, so we can better understand how and why creative activities improve wellbeing for different people.

Effective facilitation of creative activities is important for wellbeing outcomes.

Policy makers – develop support programmes to identify and grow the skills,

experience and knowledge needed for effective facilitation of creative activities. Use large-scale national and mega events as opportunities to test and learn the workforce support and training that enables creative practice expertise. Work with researchers and practitioners to broaden understanding of effective practice expertise, so that more people can get involved in delivering wellbeing through creativity.

Practitioners – continue to deliver facilitated activities, and ensure that learning about the skills, experience and knowledge of creative practitioners is used when recruiting and training their creative workforce.

Researchers – continue to build the evidence on the role of facilitators and

creative practice experts, ensuring full reporting of the characteristics, experience and skills they bring to interventions.

Building creative practice expertise

The role of the artists or expert practitioner in facilitating activities is an important mechanism for supporting wellbeing.

Some projects paired creative professionals – such as curators, artists or musicians – with other roles – such as community development workers, social workers, or

gardeners. The combination was determined by the setting, activity type and population needs.

Effective facilitation was associated with some specific personal outcomes:

- Happiness and joy

- Hope and optimism

- Self-esteem or self-care, coping better

- Meaning and purpose

- Improved mindset and new perspectives

- Belonging, connectedness, and reduced loneliness

- Better communication and self-expression

Ingredients of successful approaches:

- Understanding and valuing the people they are working with their motivations and aims.

- Supporting self-expression and emotional release.

- Enabling autonomy and choice, including over the design of the activity.

- Encouraging curiosity and experimentation, and sharing their knowledge of artistic methods.

- Fostering positive interactions and relationships.

However, the studies didn’t explore what training, skills or experience were necessary for effective facilitators.

Case study: Unlocked

Unlocked was a social prescribing intervention aimed at improving the wellbeing of prison inmates and probationers through arts workshops in prisons and community settings.

Soft Touch Arts delivered workshops where artists facilitated participants to learn and create their own meaningful artworks.

Referring to participants as artists was the first and crucial step in establishing a positive relationship between facilitators and participants.

The artist facilitators enabled wellbeing outcomes for participants by:

- Giving them a choice of activities

- Supporting individual learning journeys

- Creating a safe space for experimentation

- Helping to set goals

- Guiding and sharing expertise

- Engaging participants on an equal footing as artists themselves.

“While Unlocked practitioners do not wish to be seen as leaders and authority figures, they do begin the program in the role of leaders, guiding the volunteers through workshops and encouraging and reassuring them as they engage in creative activity.”

The programme’s approach prioritised hope, connectedness, meaning and empowerment – in contrast with more common rehabilitation interventions which focus on risk of reoffending.

Atherton, S., Knight, V., & van Barthold, B. C. (2022). Penal arts interventions and hope: outcomes of arts-based projects in prisons and community settings. The Prison Journal, 102(2), 217-236

Recommendations for the social purpose lab

The UAL’s Social Purpose Lab has a unique role and opportunity to grow our understanding of the links between creativity and wellbeing.

Alongside the general recommendations for policy, practice and research, we recommend that the Social Purpose Lab:

- Shares and grows this evidence to support better decisions for improving wellbeing through creativity.

- Explore the role of creative practice expertise in delivering wellbeing outcomes by leading a national conversation across sectors and places.

- Support research to understand the role of a creative education on wellbeing across the lifecourse, including longitudinal studies of creative

students and graduates. - Work with the education and skills sectors to understand how creative habits can be encouraged and supported across all ages and especially for people who are less likely to be creative.

- Nurture a new generation of creative practice experts and support a diverse workforce with strong creative skills and experiences.

Suggested citation

Abreu Scherer, I. and Musella, M. (2024) Creativity and personal wellbeing – contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

The written content of this briefing is available under the Creative Commons licence CC BY-NC-SA 4

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]