Life satisfaction - what works?

The quick read

We conducted two rapid reviews:

- Life Satisfaction Intervention Review: Collating international evidence on activities, programmes or services intended to improve individual life satisfaction.

- Life Satisfaction Determinants Review: Updating the evidence base using UK longitudinal data on broad factors that are associated with life satisfaction at a population-level.

Together, they provide a broad overview of the current evidence base on life satisfaction by offering a macro and micro view of what works to improve life satisfaction.

This briefing summarises the key insights from both and presents implications for research alongside recommendations for effective policy and practice.

Overall, we found:

- Strong evidence that emotional skill development, psychological therapies, exercise, and some emotion-based interventions work to improve life satisfaction.

- Strong evidence that education, employment, income, physical health, arts and culture have a well established association with life satisfaction.

- Evidence gaps in the interventions literature, including work-related interventions and interventions for specific population groups.

- Mixed or weaker evidence about the impact of community belonging and cohesion, environment, and travel on life satisfaction.

A priority next step is to connect these evidence bases together to expand intervention research into new areas, supported by the existing determinants research. We suggest prioritising the evaluation or trialling of interventions:

- in the workplace;

- being delivered to vulnerable groups;

- where there is currently insufficient evidence like music or social media interventions;

- that are linked to important determinants of life satisfaction like employment, education or close social relationships.

The reviews were conducted by Kohlrabi and were funded by the Cabinet Office Evaluation Task Force, the Department for Culture, Media, and Sport, and the Department for Transport.

This project is part of our efforts to systematically identify and summarise the evidence that uses global wellbeing measures to understand what works to improve wellbeing.

Previously, we have explored the UK wellbeing evaluation literature that uses the ONS4 and Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) measures. Insights from the 2024 life satisfaction review are intended to be used alongside these.

Background

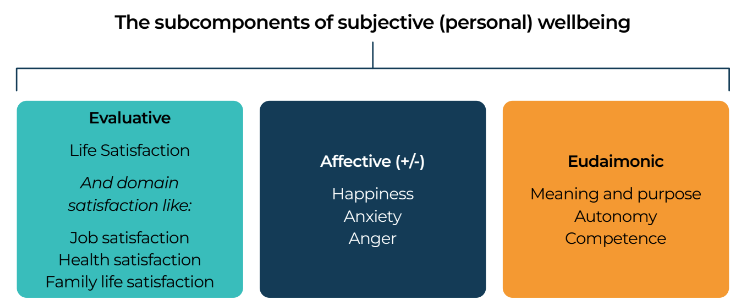

Life satisfaction is thought to be a core component of subjective (personal) wellbeing. It can be defined as “a person’s cognitive and affective evaluations of his or her life” It encompasses a holistic view that reflects one’s perceptions, opinions, and evaluations of their circumstances.

Life satisfaction as a subjective wellbeing measure

Validated quantitative measures of life satisfaction are established and widely-used across different areas of research globally, meaning we have rich data.

Examples of measures include:

- The ‘ONS4’ single-item measure: “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?” with responses on a 0-10 scale where 0 is ‘not at all’ and 10 is ‘completely’;

- The five-item Satisfaction With Life Scale: five questions using a 0-7 response scale that produces a single overall score out of 35.

They all provide a useful metric for researchers to investigate wellbeing and single-item scales in particular are increasingly used by economists to capture the monetary benefits of wellbeing impacts.

Over 80% of interventions included in the life satisfaction intervention review used multi-item measures of Life Satisfaction.

Over 75% of studies included in the life satisfaction determinants review used single item measures of Life Satisfaction.

The ‘ONS4’ single item measure of Life Satisfaction was only used in 2% of interventions and 10% of studies in the life satisfaction determinants review.

Due to the variety of measures, we have used differences in average (mean) life satisfaction scores for the intervention review and have used a descriptive approach in the determinants review to compare and understand impact.

The findings

Our full research findings are presented in the technical report. Here we summarise key insights from each review.

Life Satisfaction intervention review – key findings

The research question for this review was:

What is the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving life satisfaction across the life-course?

The review identified a large international evidence base of high-quality studies.

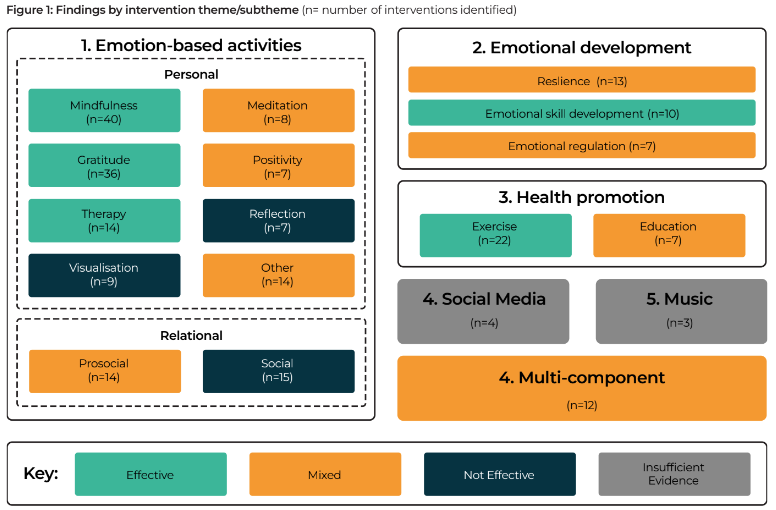

Two-thirds of included interventions are emotion-based activities.

The efficacy of the interventions in improving life satisfaction is mixed, with some types appearing promising and others not providing statistically significant results.

Of the 234 interventions included approximately:

- 25% were focused on to university students

- 20% were focused on children or young people

- 20% were focused on adults over 50

- Just under half were conducted in Europe

- Almost 40% were conducted in North America.

- Less than 5% were delivered to groups who might typically be considered to be vulnerable or have low wellbeing (for example we found interventions for informal carers of people receiving palliative care and children in foster care)

The interventions were delivered in a range of settings including schools, homes, online, health and community centres, universities, nursing homes and outdoors.

We sorted interventions into six key themes:

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Emotion-based activities | Interventions focused on delivering activities which engage participants in emotional development.* |

| 2. Emotional development | Instructional interventions on the nature of emotions, how and why they occur, and developing ways to effectively manage feelings.* |

| 3. Health promotion | Interventions that promote a healthy lifestyle, including exercise, diet and sleep. |

| 4. Social Media | Interventions that involve changes to social media use, typically reduction or abstinence. |

| 5. Music | Interventions that involve participants engaging with some form of music, such as singing or playing instruments. |

| 6. Multi-component | Multi-faceted wellbeing programmes with several components. |

*The distinction between themes 1 (emotion-based activities) and 2 (emotional skills development) is that 1 primarily involves activities and 2 primarily involves instructional teaching.

Findings by intervention theme/subtheme

Of the 18 discrete themes/sub themes:

- Five appear to be effective at improving life satisfaction

- Eight provide mixed evidence that they may improve life satisfaction

- Three did not provide statistically significant results that they improved life satisfaction

- Two had insufficient evidence to draw conclusions

Where interventions are effective, they mostly have a small effect on life satisfaction. We found Emotional Skill Development to have a moderate effect.

For a deeper dive which includes descriptions of all the sub themes and further insights into the effectiveness of interventions, see the supplementary information.

- Our strict inclusion criteria may be obscuring some less well developed evidence or interventions which do not suit being part of an RCT or quasi- experiment – for example because they are not time-bound or easily controlled.

- Interventions in other areas of research may not include validated life satisfaction measures – for example interventions to help people into work or to make homes more energy efficient.

- The databases we used for our search were not comprehensive and did not include every field of evidence.

Life Satisfaction determinants review – key findings

The research question for this review was:

What are the long-term determinants of life satisfaction?

This review identified 49 studies conducted in the UK. All were panel or cohort studies, with over half using a sample of over 10,000 individuals.

Of the 49 studies we reviewed:

- Over a third followed up with participants between 6-10 years after the first survey.

- Over a fifth followed up between one and five years later.

- The remainder followed up over 11 years later.

We sorted interventions into six key themes:

| Theme | Subtheme | Description | Evidence summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial situations (n=12)* | The effect of income, resource ownership and social mobility | Significant with consistent associations across different cohorts | |

| Education and Employment (n=14) | Employment (n=9) | The effect of job transitions and working conditions | Significant with consistent associations across different cohorts |

| Education and Employment (n=14) | Education (n=5) | The effect of qualifications and learning | Significant with consistent associations across different cohorts |

| Social capital (n=12) | 3.1 Community (n=7) | The effect of belonging including citizenship, internal migration, neighbourhood participation, loneliness | Inconclusive. Only change of address (internal migration) had a significant positive association |

| Social capital (n=12) | Social support (n=5) | The effect of relationships, including social networks, informal caregiving, parenthood and living together | Significant with consistent associations across different cohorts |

| Health (n=11) | Physical and mental health (n=6) | The effect of poor health | Significant but with inconsistent associations across different cohorts |

| Health (n=11) | Health behaviours (n=5) | The effect of diet and exercise | Inconclusive Fruit and vegetables intake (positive association) and problem drinking (negative association). |

| Environment (n=4) | The effect of infrastructure, access to blue and green spaces, commuting | Inconclusive Perception of public transport access was significantly associated |

|

| Arts and culture (n=5) | The effect of participation and engagement | Significant but with inconsistent associations across different cohorts |

*n= number of studies in each theme/sub-theme. n does not sum to 49 as many studies explored multiple factors.

For a deeper dive into factors found to have significant associations with life satisfaction, see the supplementary information.

The research

How did we do it?

We worked with researchers from Kohlrabi to answer the two research questions. Each review was conducted separately but we used similar search criteria to ensure they would be complementary.

Search strategy

For inclusion in the reviews, studies had to meet these criteria:

| Intervention review | Determinants review | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | General population | General population |

| Focus | Intervention(s) aimed at improving life satisfaction | Long-term association between any factor and life satisfaction |

| Comparator | Present comparison data from a control group | N/A |

| Study design | RCT, experimental, quasi-experimental | Observational (panel and cohort surveys) |

| Timeframe | 2011 - present | 2011 - present |

| Language | English | English |

| Geographical scope | High-income OECD countries | UK only |

| Studies identified | ||

|---|---|---|

| Studies screened (abstract) | 9,530 | 5,721 |

| Studies screened (full-text) | 519 | 1,096 |

| Studies included | 189 studies with 234 interventions* | 49 |

*Some studies tested more than one intervention

Studies were excluded if they were:

- on a ‘clinical’ population1A population with a formal medical diagnosis where the intervention was being delivered in response to that diagnosis. Individuals with a range of diagnoses may have taken part in studies but researchers were not delivering the interventions to populations that had been sampled because of their medical diagnosis. As a result research into, for example, improving the life satisfaction of cancer patients would not be included.

- related to the COVID-19 pandemic

Full flow diagrams of the searches, screening process and exclusion criteria can be found in the technical report. The international studies excluded from the life satisfaction determinants review and the COVID-19 studies from both reviews can be found on the What Works Wellbeing Website.

The strict inclusion criteria has resulted in a set of studies that score very highly on tools from the Joanna Briggs Institute that assess quality.2For more information see “2.6 Data extraction and critical appraisal” in the technical report page 13 As such, we can have confidence in the findings of the studies.3Using the Maryland Scale. these interventions all meet the primary Level 3 criteria: “Comparison of outcomes in treated group after an intervention, with outcomes in the treated group before the intervention, and a comparison group used to provide a counterfactual.” For more information on the Maryland scale please see: https://whatworksgrowth.org/resource-library/the-maryland-scientific-methods-scale-sms/

Study design

Randomised Controlled Trials, experiments or quasi-experiments can provide causal evidence through the use of a control group which does not receive the intervention. Randomised controlled trials are regarded as a very high standard of evidence.

In observational studies, researchers do not intervene in the participants’ lives but rather track them over time.

Approach to analysis

For both reviews, the research team and experts from the centre mapped interventions and determinants into themes and sub-themes.

To understand the effectiveness of interventions we:

- used differences in average (mean) life satisfaction scores from before to after the intervention, comparing the intervention and control groups. We used the first available follow-up after the intervention had been completed.

- used meta-analysis to compare effectiveness within some sub-themes, where appropriate.

For the determinants review we:

- took a narrative approach, pulling out key findings where available, as studies used contrasting statistical approaches and did not always present findings in ways that allowed quantitative differences to be easily compared. We explored changes to factors over subsequent waves of surveys which varied in length from survey to survey – this is noted in the technical report.

Read more about our analytical approaches and their limitations in the technical report.

Research implications

The findings of the review raise important implications for future research.

Life satisfaction intervention review

| Finding | Implications for future research |

|---|---|

| The review identified an intervention evidence base that was heavily skewed toward emotion-based activities like mindfulness and gratitude, with insufficient evidence for other types of intervention like music and social media. | This was not a full systematic review and so some evidence types could be missing. To provide a more complete view of the evidence future work should: - Review excluded evidence like COVID-19 studies, those conducted with clinical populations - Expand the review using additional research databases - Review less robust evidence like pre-post evaluations without a control group to identify ‘promising’ and ‘initial’ evidence - Conduct a rapid evidence review of ‘natural experiments’ which observe changes in life satisfaction as a result of policy change (for example after major policy changes like the introduction of Universal Credit). This body of evidence regularly did not meet our inclusion criteria and so is not present in this review. In addition to fully capturing the existing intervention evidence base, future research must address the gaps identified in this review like the intervention themes of music, social media and relational emotion-based activities. |

| Interventions identified were disproportionately focused on certain groups (like children, students and older people) over others groups (like vulnerable populations and adults in the workplace). | Commission further analysis of the interventions included in this rapid review on the basis of population. Review the evidence on children, students and older populations to generate more detailed insights on what works to improve their wellbeing. Prioritise research for key groups that were missing or under-represented in the interventions such as: adults in the workplace; groups we know to have low wellbeing (for example unemployed individuals or those living in poverty); and marginalised groups. |

| There were a lot of multi-component interventions which blend different approaches to improving wellbeing within a single intervention. | Test each individual element of an intervention separately to identify the relative contributions of different elements of multi-component interventions. Prioritise research into multi-component interventions where we know both individual elements are effective (for example therapeutic approaches and exercise or emotional skills development and gratitude). |

| There were a range of intervention characteristics which may be important but it was difficult to understand their relative contribution to improvements in life satisfaction. | Construct trials and quasi-experiments to help identify the key characteristics of successful interventions. Factors we have identified that are likely to be important include: duration and frequency of sessions (intensity of intervention), group vs individual interventions, online or in-person delivery, delivery setting, and level of training received by those delivering interventions. |

| Interventions like reflection, visualisation and ‘social’ relational emotion-based activities were not found to be effective. | Further exploratory evaluations and small scale trials are needed to see if these interventions can be effective to improve life satisfaction in particular populations or contexts. It may also be that they are effective for other aspects of wellbeing like positive affect or eudaimonic wellbeing. |

| While the studies included were of high quality, there are still methodological improvements that could be made. | The most common sample size of individuals receiving the intervention was between 21 and 50 individuals. Larger studies would provide more reliable evidence and could allow for analysis by sub-group. Include appropriate follow-up assessments of life satisfaction to see if improvements have been sustained, especially one-year after receiving an intervention. Replicate the most promising interventions to ensure they are effective. Improve approaches to blinding to reduce bias and improve reporting of methods to understand and/or reduce/quantify attrition. |

Life satisfaction determinants review

| Finding | Implications for future research |

|---|---|

| There was a large international evidence base. | Review the excluded international evidence (548 studies). |

| Many significant factors associated with life satisfactions were mediated by age, gender, income, educational attainment, ethnicity, sexuality, disability etc. | Explore how associations might vary for different groups within populations sampled, particularly for groups who we know to be more likely to experience low wellbeing. |

| Mixed evidence for areas where associational relationships are complex such as resource ownership, additional training, migration and moving, community engagement and mental health. | Further develop our understanding of how the impact of a determinant may vary over time by exploring associations at multiple follow-up points. For example, additional training may not increase life satisfaction two years later but could be associated with improvements in life satisfaction in subsequent decades. |

| No strong associational relationships between life satisfaction and factors including Brexit, flexible working policies, gym membership, commute time and proximity to the coast were found. | Explore how associations might vary for different groups within populations sampled, particularly for groups who we know to be more likely to experience low wellbeing. |

| Longitudinal studies, especially cohort studies, have a historical bias - associations found in the past may not hold in the present. | Use the latest evidence and publish results rapidly to allow nearer real-time analysis. Continue to commission large-scale birth cohort studies on a regular basis. |

Considering the reviews together

While each review was carried out independently, they were designed to be complementary. As such, it is important to consider what they tell us about life satisfaction collectively.

There are some promising overlaps:

- Health – The determinants review highlighted health as a driver of life satisfaction, and the intervention review found a number of effective health interventions. Short- term interventions focused on health may support long-term improvements in wellbeing.

- Arts and culture – The determinants review showed association between life satisfaction and arts and culture. The intervention review found a small number of effective interventions that used musical activities to improve life satisfaction.

There are also gaps:

- Income and employment are critical factors for life satisfaction but there were only 20 interventions delivered in an employment context to working adults/in the workplace. Of these only five saw a statistically significant improvement in life satisfaction.

- Social support – is identified as closely associated with life satisfaction in the determinants review. While the intervention review found 15 interventions that promoted the benefits of social interactions, none saw a statistically significant improvement in life satisfaction. These interventions may improve other areas of wellbeing, but they do not seem to be associated with life satisfaction in the same way as key relationships like a spouse or parent relationships are.

These examples bring to life the primary challenge of the two reviews: the gap between the macro-level, long term drivers of life satisfaction in the determinants review and the available individual-level or micro interventions shown to improve life satisfaction in the intervention review.

Currently, it is not easy to build a clear theory of change that links specific individual interventions like emotional skills development and therapy (micro-level) to important determinants, such as satisfying employment, educational attainment, or strong relationships (macro-level).

The determinants review identifies many of the foundational blocks of our life satisfaction – income, employment, education and social relationships. These might change “by chance” (for example through bereavement) or through long-term effort (for example gaining an additional qualification that opens up new opportunities).

The intervention review identifies specific and targeted activities that we might use as an individual to try and manage our life satisfaction like exercise, mindfulness, therapy or through the development of our emotional skills.

The relationships between different interventions and their impacts on the determinants of life satisfaction are complex. If we can construct pathways of interventions to secure important determinants of life satisfaction we could make important improvements in overall wellbeing. Interventions that produce even small but sustainable increases in life satisfaction are desirable, especially if they can be delivered to large populations at low cost.

To make progress, we need to establish more connections between the two evidence bases. The table below provides some prompts for interventions based on factors associated with life satisfaction in the determinants review and known policy interventions related to them. It is not exhaustive and is intended to aid thinking.

| Determinants review themes | Prompts for interventions |

|---|---|

| Economic & Financial Situation | Reducing the gender pay gap, energy efficiency measures in homes, access to affordable credit, inheritance planning, pension planning, reducing poverty, maximising household incomes |

| Employment | Youth unemployment, return to work schemes, disability and long-term sickness support, flexible working, hybrid working, four-day week, employee benefits, workplace health and wellbeing schemes, returning to work after pension age. |

| Education | NEET support, lifelong learning, apprenticeships, T-levels, work-based training, sabbatical policy, retraining support |

| Social capital | Marriage counselling, family counselling, carers allowance, adult social care support, bereavement support, neighbourhood events, town centre regeneration, regularising immigration status, community clubs, organisations and activities, parenting support, loneliness support. |

| Health | Access to primary care, including opticians and dentistry, disability support and benefits, smoking, drug and alcohol services, public health programmes for mental health, physical activity, healthy eating etc. |

| Environment | Bus and rail service improvement, commute time reductions, active travel infrastructure, low traffic neighbourhoods, parking improvement, air & water quality improvements, increased access to green and/or blue space |

| Arts and Culture | Uniformed groups, creative opportunities, community outreach by museums, galleries, theatres etc. |

Recommendations for action

- Use these review findings in all stages of policy making using the HMT Green Book Wellbeing Supplementary Guidance – at strategic stages and setting policy objectives, to generate and short list options, to understand potential impacts, appraise and evaluate.

- Establish how your policy area improves wellbeing or manages risks wellbeing and which other departments or sectors contribute to your goals and vice versa.

- Add validated life satisfaction measures into existing and new evaluations of policies, projects and programmes.

- Prioritise the evaluation or trialling of interventions:

– in the workplace,

– being delivered to vulnerable groups,

– where there is currently insufficient evidence like music or social media interventions.

– that are linked to important determinants of life satisfaction like employment, education or close social relationships. - Commission regular reviews of life satisfaction evidence to ensure research is rapidly identified and made available for decision-making.

- When developing new policy, develop theories of change which link the determinants of life satisfaction to the interventions and mechanisms that have proved effective in the existing evidence base.

- Set an overarching goal to improve wellbeing and reduce wellbeing inequalities in local area Health & Wellbeing Strategies. Include assessment of life satisfaction in Joint Strategic Needs Assessments.

- Fund trials of interventions that support known determinants of life satisfaction including: employment, education, financial situations, and look to improve social capital.

- Fund larger scale trials to improve confidence and allow for meaningful analysis of sub-groups in order to develop better understanding of how different populations are impacted by an intervention.

- Fund existing trials so that a one-year follow up can be included to understand whether changes are sustained.

- Fund multi-arm trials which allow researchers to identify the key intervention characteristics that make interventions successful like duration, intensity, group vs individual interventions and delivery online or in person.

- Fund economic evaluations of any interventions undergoing a trial.

- Be cautious when funding further trials of emotion-based activities, where the evidence base is currently most developed, unless done so at very large scale or targeted at specific groups known to have low wellbeing.

- Continue to invest in large scale longitudinal and cohort surveys which include robust measures of life satisfaction and allow for meaningful analysis of sub-groups and changes over time.

- Where appropriate add life satisfaction measures into the evaluation of promising services and interventions to begin to build the evidence base needed for larger scale trials.

- When designing new support and services, develop theories of change using the evidence for what determines life satisfaction and which mechanisms have proven effective.

- Support the evaluation of promising practice to help build the evidence base needed for large scale trials.

- Where appropriate add a validated life satisfaction measure to your monitoring frameworks when commissioning services.

- Consider the impact of services on life satisfaction across the commissioning cycle: planning and assessing need, designing services, procurement, and contract monitoring and evaluation.

- Use life satisfaction data as a lens for understanding how different groups access and experience services and the outcomes they achieve.

- Pay close attention to what life satisfaction data can tell you about equity of service outcomes. Do those with low wellbeing experience similar outcomes to those with higher levels of wellbeing?

- Consider how innovative approaches that use life satisfaction measures to understand social value, like WELLBYs, could be useful in your work and support their use.

Design your studies so that the wellbeing impacts can be easily identified and monetised by:

- Including both single-item and multi-item measures of life satisfaction wherever possible within studies.

- Reporting life satisfaction outcomes in full so they can be used in meta-analyses or by economists.

- Conducting research that allows more meaningful comparison of changes in life satisfaction between metric – particularly multi vs single item measures.

- Designing research that looks at differences between populations and wellbeing inequalities of interventions.

- Incorporating appropriate long-term follow-up of interventions to provide insights into the sustainability of changes in life satisfaction.

- Ensure qualitative research methods provides evidence on the contexts and mechanisms needed for change.

Suggested citation

Abreu Scherer, I., Bignall-Donnelly, R., Crellin, R., Hey, N., Smithson, J. (2024) Life satisfaction: what works? Briefing, What Works Centre for Wellbeing

Explore more

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]