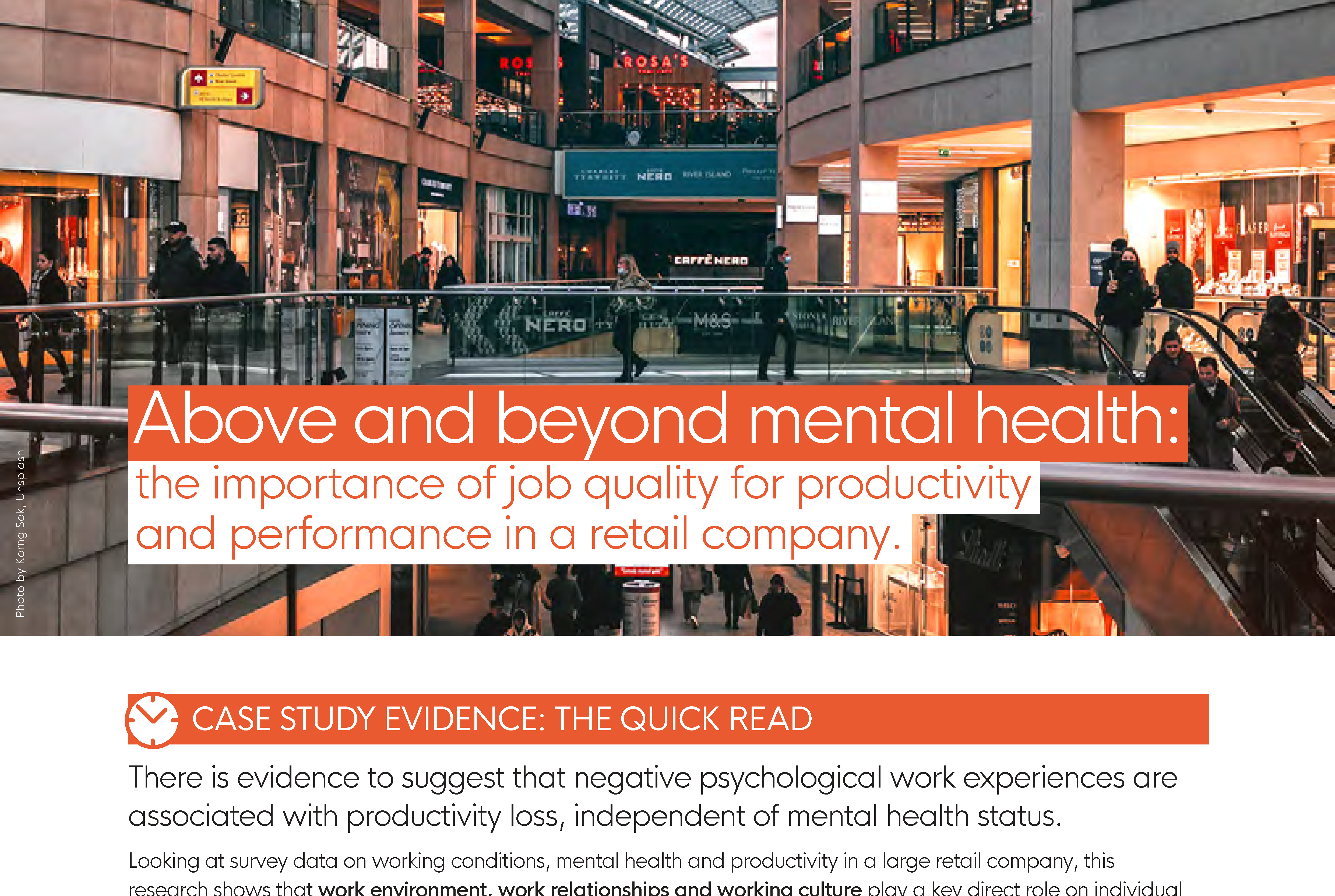

The importance of job quality for productivity and performance in a retail company

Downloads

Case study evidence: the quick read

There is evidence to suggest that negative psychological work experiences are associated with productivity loss, independent of mental health status.

Looking at survey data on working conditions, mental health and productivity in a large retail company, this research shows that work environment, work relationships and working culture play a key direct role on individual productivity and performance.

In the organisation studied, four groups of employees were derived, depending on their levels of mental health and productivity. These were content high-performers, discontent high-performers, directly at risk and overworked. The adoption of bespoke programmes for specific groups of employees, together with programmes aimed at improving the wellbeing in the workplace, may be an effective strategy.

Measurement and outcomes

Employee productivity loss was defined as:

- Absenteeism (missing work), and

- Presenteeism (working whilst impaired

It was measured using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) tool, a composite measure including:

- Hours actually worked

- Hours missed from work due to health problems

- Degree of impairment when working.

Results are expressed as a percentage of hours lost in the prior week where 0% represents no productivity loss and 100% represents complete productivity loss.

Mental ill-health was defined in line with mental distress or poor mental health. It was measured using the six-question Kessler scale which asks how respondents felt in the last 30 days. It measures if participants feel:

- Nervous

- Hopeless

- Restless or fidgety

- That everything was an effort

- So depressed that nothing could cheer you up

- Worthless

Responses are added giving an overall score of 0 to 24, with a higher score representing higher levels of psychological distress.

Job quality (psychological work factors) were measured through responses to individual statements (to what extent do you agree with statements in a five-point Likert scale), including:

- At work, I receive the respect I deserve from my colleagues

- Relationships at work are strained

- I have a choice in deciding what I do at work

- Staff are always consulted about change at work

- I am subject to bullying at work

- I have unrealistic time pressures

- My line manager cares about my health and wellbeing

- My organisation supports me to manage stress at work

- My organisation supports me when I am unwell

- I am enthusiastic about my job

- Discrimination exists in my workplace

The case

Britain’s Healthiest Workplace Survey. Jobs at this organisation varied from manual labour and customer-facing roles to office, desk-based work. Two thirds of respondents were female, and two thirds reported an annual income below £40,000. Over 70% reported no serious health conditions. We cannot be confident of how representative this case is of the sector.

Case study evidence is an important source of learning about how the different job quality aspects work in real-world settings. They can be used alongside other research to learn more about both what works, how, and why different actions make a difference to wellbeing and productivity.

What we found

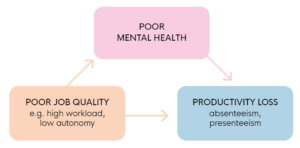

Figure 1. Association between poor job quality, productivity loss and poor mental health.

Part of the association between poor job quality and loss of productivity is independent of the impact on mental health. When examining the association between productivity and each job quality aspect individually, we observed that all job quality factors were significantly related to the likelihood of productivity loss. The current knowledge base suggests that it is by impacting on mental health that job quality affects productivity so that the impact of job quality on productivity is an indirect connection.

We looked at whether job quality can have a direct effect on productivity loss rather than just through their impact on our mental health. We did this by accounting for levels of mental health and related possible influences such as general health and lifestyle.

We found that mental health continues to be the most important factor related to productivity.

Findings also suggest that some psychological aspects of job quality have a direct association with productivity loss separately from their impact on mental health. They are:

- Enthusiasm at work

- Discrimination at work

- Bullying at work

- Frequent unrealistic time pressures

- Decision power measured by consultation about changes

The size of these associations is represented here in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Effect sizes of the association between productivity loss and mental health and psychosocial work factors. Grey bars represent non-significant associations at 95% confidence level.

These associations do not imply causality, but they were controlled by the following socio-demographic factors:

- Age

- Annual income

- Highest level of education

- Marital status

- Ethnicity

- Region

- Serious health conditions

- Body mass index

- Physical activity

A typology of retail employees

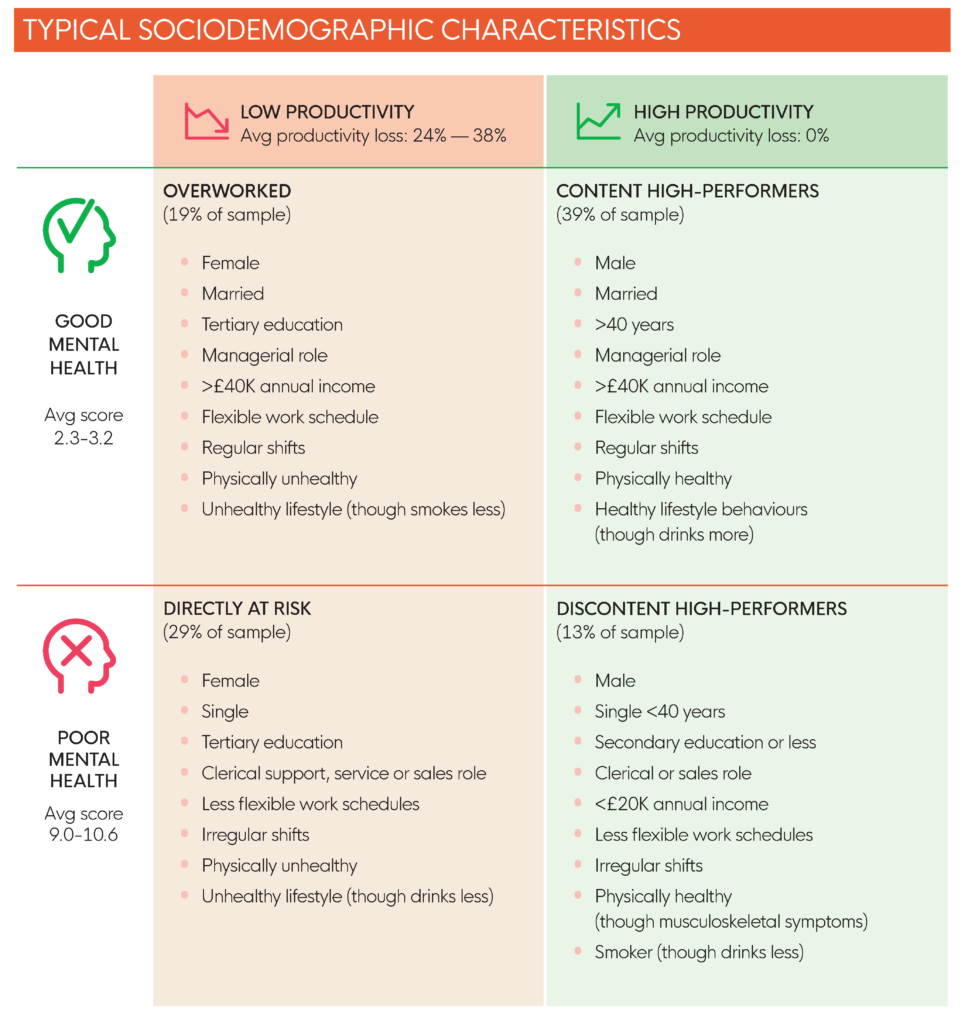

The sample of respondents was grouped into four clusters depending on their scores on mental health and productivity based on good/bad mental health and high/low productivity.

We know the effect of mental health on productivity so we expected to find many people in two of the clusters – content high performers 39% and directly at risk 29%.

Clusters 2 and 3 – overworked 19% and discontent high performers 13% – represent more paradoxical cases. We expect that part of the productivity levels are explained not only by employees’ mental health but also by different health and lifestyle behaviours and the characteristics of their job.

Psychosocial work factors and productivity

Typical sociodemographic characteristics

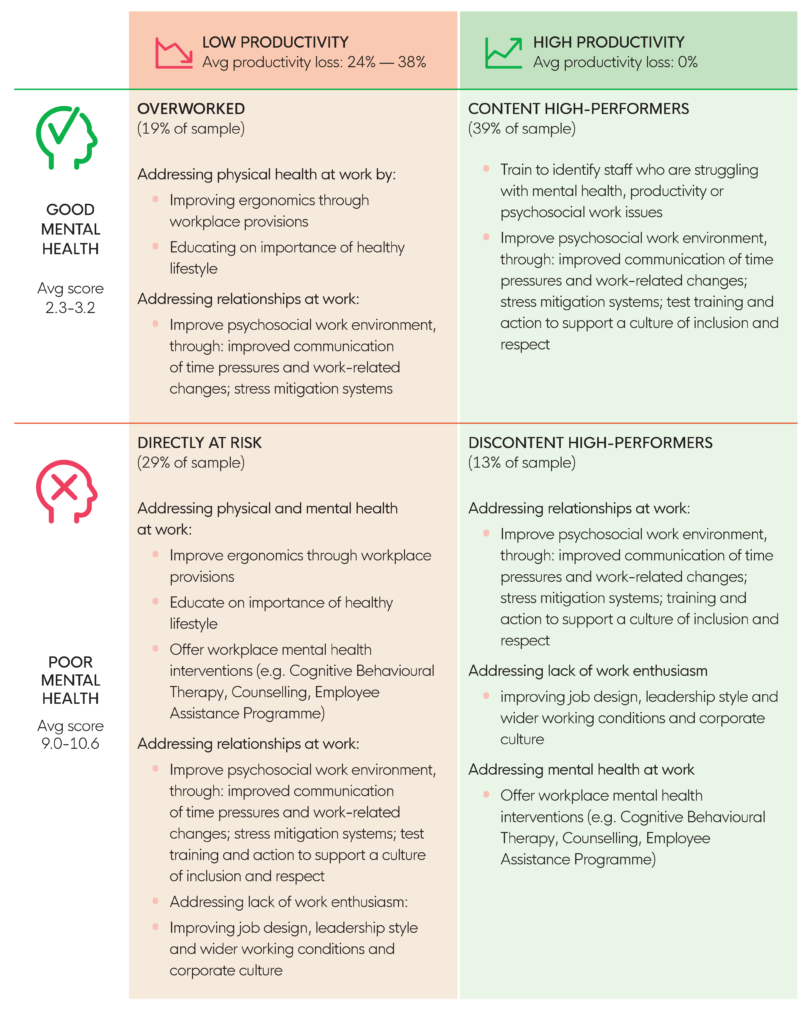

Recommendations for action

With these findings, below are the recommendations and implications for employers, HR staff and wellbeing leads. What do we know about the recommended approaches?

What do we know about the recommended approaches?

Ergonomics

Although few studies have directly measured the impact on mental health, encouraging employees to break up excessive sitting with light activity (e.g. dynamic workstations, standing meetings) is associated with reduced depression and anxiety symptoms.

Healthy lifestyle education

Workplace health promotion can have benefits for physical health markers and psychological wellbeing. The effects of work-place health promotion on mental health are stronger if mental health promotion is included in the overall package of activities and the effects are stronger where there are activities at least once a week.

Mental health training

Although the literature is limited, there is some evidence that peer support (i.e. sharing of experiential knowledge, skills and social learning between employees to support recovery from mental health problems) can have a positive impact on mental health.

The evidence is more mixed about training in mental health awareness.

Anti-bullying/anti-discrimination training

There is no conclusive evidence that unconscious bias training changes attitudes in a lasting way.

Simple shared activities (e.g. workshops, social events) can improve wellbeing and performance by improving workplace social atmospheres.

A sense of belonging and shared values in the workplace may help maintain wellbeing and organisational performance through adversity.

Stress management

Systematic reviews of training to develop personal resources, or training for stress management, found inconsistent results for wellbeing outcomes.

Job design

Evidence shows that attempts to improve job quality through job redesign (i.e. changes to ways of working) may improve wellbeing and sometimes performance, if done alongside training.

Leadership and people management

Good people management practices (e.g. give space for decision making, clarify roles, promote team work, learning, and feedback) are associated with lower levels of staff sickness absence, higher customer satisfaction and more satisfied staff.

Training leaders to be effective and supportive in managing employees may enhance wellbeing for both managers and employees, when the most appropriate learning process is used and in the right context.

Research implications

More evaluations are needed to understand specifically what actions work to improve both wellbeing and performance. Research on the evidence behind promising interventions has already been carried out, but we still need to analyse what happens if we do things differently, as changing a company’s workplace culture can be the main mechanism for change.

It is also necessary to bear in mind that these findings correspond to pre-Covid measurements and so some job characteristics are expected to play out differently during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

This case study methodology is a starting point. More causal evidence is needed about the links between workplace wellbeing and productivity, contextualised in different industry sectors. The coefficients of the associations between job aspects and productivity can be small but, from an economic and decision-making point of view it can be impactful to focus on such productivity outcomes. More information is also needed on specific job characteristics and it is necessary to understand what characteristics may have an influence on wellbeing.

Data and methods: regression and clustering analysis with survey data

As part of a research programme supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant no. ES/S012648/1), researchers from RAND Europe conducted quantitative analysis based on survey data from one big retailer organisation.

The survey, Vitality’s Britain’s Healthiest Workplace, covers organisations in England, Scotland and Wales. Organisations from a wide range of sectors opt-in to participate and then employees take part on a voluntary basis. The self-reported data is collected annually and analysed cross-sectionally. For this analysis we used data

from one participating organisation that took part in the 2018 and 2019 waves (n=3,170 individual respondents).

The data analysis included:

- Ordinal logistic regression models with productivity loss as outcome measure: different models which progressively included all psychosocial work factors combined (Model 1); mental health (Model 2); other work factors (Model 3); and demographics (Model 4). Odds ratio (OR) were calculated to express the relationship between each explanatory variable and loss of productivity.

- Descriptive clustering analysis: respondents were segmented into 4 groups depending on their productivity loss (0% or >0%) and their mental health (below or above the average Kessler score of 5.8). These cut-off points were arbitrary.

Suggested citation

Phillips W, Romanelli R, and Soffia M. Case Study Evidence. Above and beyond mental health: the importance of job quality for productivity in a retail company, Briefing, June 2022, What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]