What matters for mental health and productivity in a financial services firm?

Downloads

Case study evidence: the quick read

In the organisation studied:

- Poor employee mental health can be related to some job-specific and working-culture characteristics such as: shift work, lack of flexible hours, unsupportive managers and strained working relationships.

- Bullying and not being supported to manage stress were two factors jointly related to staff mental health and productivity.

- The negative relationship between poor job quality and mental health and productivity may be stronger for ethnic minorities.

- Working from home increased productivity loss, while unrealistic time pressures were related to decreased productivity loss.

- Findings suggest that roles which have less flexibility need more attention paid to protective factors.

Context

Survey data for different organisations shows a deterioration in mental health over years, in parallel to increases in productivity loss, suggesting these could be correlated (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average mental ill-health (Kessler score) and productivity loss for British Healthiest Workplace respondents over time.

The literature indicates that poor psychological working conditions, (including work environments, unclear roles, heavy work demands, low involvement in decisions, and unsupportive management) are associated with poor mental health. Poor mental health is, in turn, associated with lower productivity through presenteeism and absenteeism.

Evidence also suggests that psychosocial work factors can be related to productivity levels independent of an employee’s mental health.

Measurement and outcomes

Employee productivity loss was defined as:

- Absenteeism (missing work), and

- Presenteeism (working whilst impaired)

It was measured using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) tool, a composite measure including:

- Hours actually worked

- Hours missed from work due to health problems

- Degree of impairment when working

Results are expressed as a percentage of hours lost in the prior week where 0% represents no productivity loss and 100% represents complete productivity loss.

Mental ill-health was defined in line with mental distress or poor mental health and it was measured using the six-question Kessler scale which asks how often respondents have had the following different feelings or experiences during the past 30 days:

- Nervous

- Hopeless

- Restless or fidgety

- That everything was an effort

- So depressed that nothing could cheer you up

- Worthless

Responses are added giving an overall score of 0 to 24, with a higher score representing higher levels of psychological distress.

Job quality (psychological work factors) were measured through responses to individual statements (to what extent do you agree with in a five-point Likert scale), including:

1) Relationship factors (more indirectly controlled by the employer through workplace culture):

- Relationships at work are strained

- I receive the respect at work I deserve from my colleagues

- My line manager cares about my health and wellbeing

- I am subject to bullying at work

2) Other work factors (more directly controlled by the employer through established workplace policies):

- Staff are always consulted about change at work

- I have a choice in deciding what I do at work

- I have unrealistic time pressures

- My organisation supports me to manage stress at work

- Are you able to work flexible hours?

- Discrimination exists in the workplace

- Commute into work is an hour or more

- Are you able to work from home (at least some of the time)?

- Do you work irregular hours (e.g. shift work)?

The study

The findings described here are based on the responses provided by an international financial services firm to Britain’s Healthiest Workplace Survey between 2015 and 2019.

Both mental health and productivity have been diminishing year on year in the organisation, following the same trend as the whole Britain’s Healthiest Workplace sample (Figure 1), although average scores are better for the case study, possibly because of their higher income.

Internal administrative data from the case study company showed that mental health disorders were the fourth most expensive issue by private health insurance claims and the fifth most expensive by number of GP referrals made.

While we cannot be confident of how representative this case is of the sector, case study evidence is an important source of learning. By assessing specific groups and contexts we can examine how job quality factors impact employee mental health and performance in real life situations to aid our understanding of workplace wellbeing and what works to improve it.

What we found

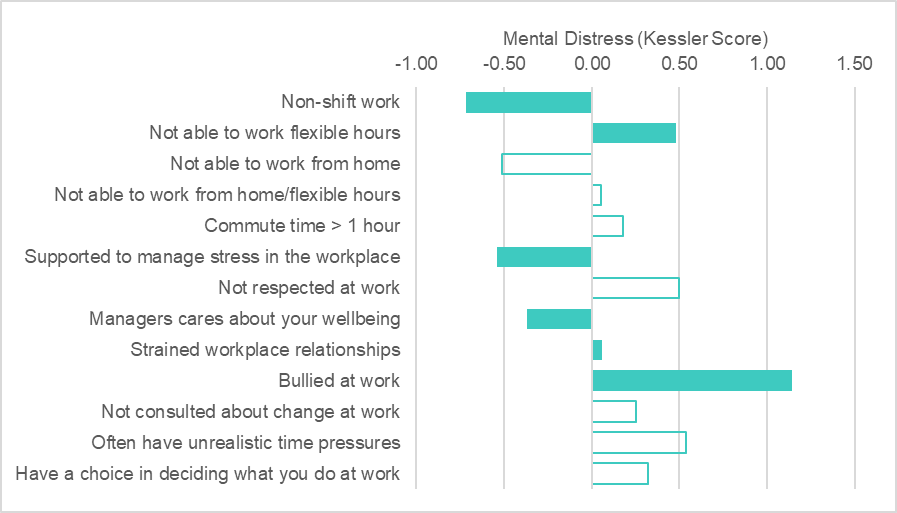

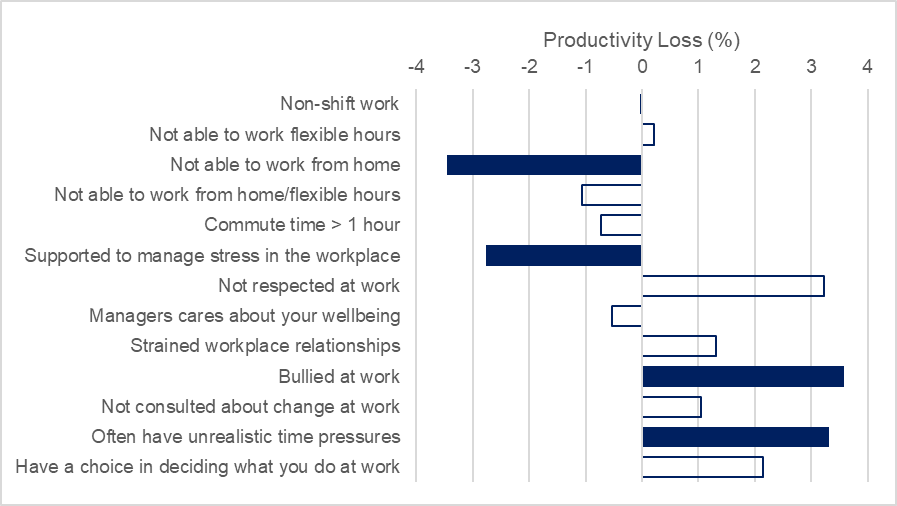

Poorer mental health was associated with the following factors (Figure 2):

- Being bullied

- Having shift work

- Not being supported to manage stress

- Not being able to work flexible hours

- Having a manager who doesn’t care for your wellbeing

- Strained work relationships

Productivity loss was associated with the following factors (Figure 2):

- Being bullied

- Being able to work from home

- Having unrealistic time pressures

- Not being supported to manage stress

Figure 2. Magnitude of relationships for mental health and productivity. (Shaded columns indicate the greatest statistical confidence of a significant relationship). All the results are associations rather than causal relationships. The strength of the association is given by OLS regression coefficients for mental health and productivity. Variables that could influence outcomes are year, age, income, gender, education, marital status, ethnicity, BMI, exercise, smoking, MSK symptoms, serious health conditions, job type and individual repeater effects.

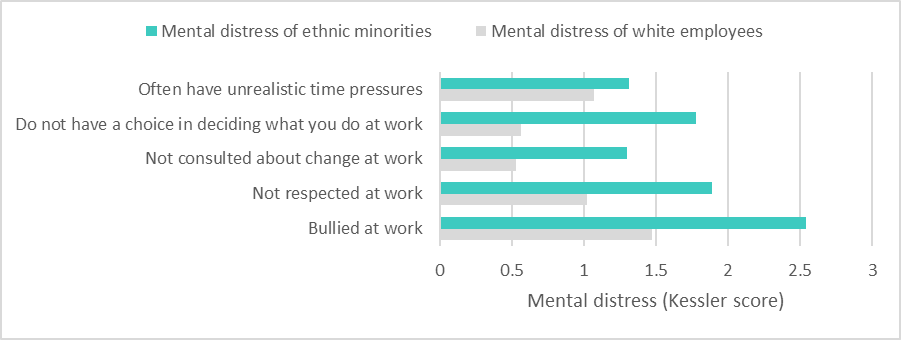

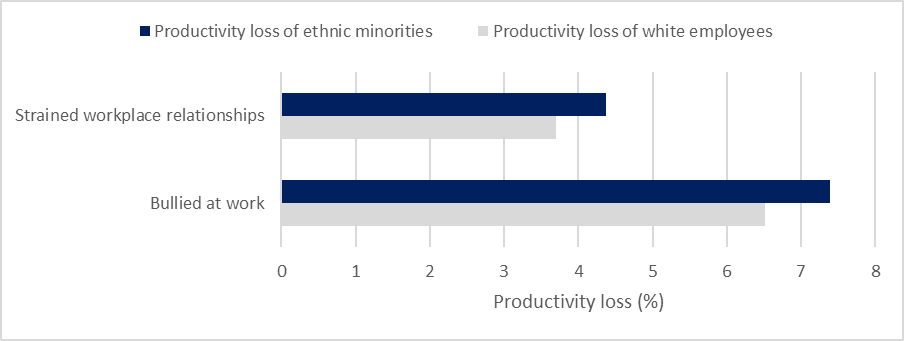

Racial discrimination and general discrimination in the workplace were only asked in 2018 and 2019 waves therefore these were analysed separately from other work factors. It was found that those who believe there is discrimination have poorer mental health and are less productive at work (as shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3. Magnitude of relationships for mental health and productivity, by ethnicity. Magnitudes are given by OLS regression coefficients for mental health and productivity, by ethnicity. Control variables are survey year, age, income, gender, education, marital status, job type and individual repeated effects. All these results are associations rather than causal relationships.

The association of relationship factors and other work factors with mental health and productivity was analysed separately for white and minority ethnicities (Figure 3). It was found that the following was more detrimental for the mental health of ethnic minorities compared to white employees:

- Not being consulted at work

- Not having a choice in deciding what to do

- Having unrealistic time pressures

- Being bullied at work

- Not being respected at work

Meanwhile, bullying and strained workplace relationships were more strongly associated with the productivity levels of ethnic minorities than with white employees (Figure 3).

The influence of some organisational factors are largely out of the control of individuals, which means that interventions targeting only individual behaviour change can have limited impact.

Recommendations for action

With these findings, below are the recommendations and implications for employers, HR staff and researchers.

Tackling employee wellbeing does not need to compromise performance.

A good organisational approach to employee wellbeing is one that measures, tracks and, where necessary, improves job quality to prevent mental ill health and sustain productivity.

An organisational approach that addresses several job quality factors may be complementary to targeting individual employees to develop coping skills.

Job quality aspects other than work relationships can be easier to target via company-wide approaches, e.g.:

- Informing employees of planned workplace changes through establishing good communication networks

- Involving workers in decisions that affect their work through collaborative goal setting and team work

- Reducing time pressure / workload through allowing flexible work arrangements

Aspects related to work relationships can be targeted through, e.g.:

- Simple teamwork and shared activities to help create an open and supportive workplace culture

- Training leaders in mental health awareness to support a more compassionate and effective line management

Overall, a few job quality aspects can be identified to improve mental health and performance. We need evaluations to understand what actions or interventions contribute to change those aspects. For this, it is recommended to use adequate comparable measures, including metrics on job satisfaction and life satisfaction as outcomes.

What we need to know more about

The relationship between working arrangements and productivity in the case study may seem conflicting. We might have expected greater flexibility in terms of place and hours to be related to increased productivity, however the opposite was found.

This could be because at the firm studied working from home is the exception rather than the norm. Employees could be working from home because they are unwell, rather than taking a sick day, which would negatively impact their productivity.

The data from this case study predates the global pandemic by up to five years. As the implications of the virus saw a widespread shift in working culture, particularly in terms of flexibility and home working, we should be cautious in how we apply these current findings.

To better understand whether this is sector specific, or time-bound, we need more understanding of the impact of Covid-19 on mental health and productivity in the workplace.

More evaluations are needed about addressing loneliness in the workplace.

An evidence gap remains as to whether relationship factors or other factors are more important for mental health and productivity in the working environment.

Data and methods: regression analysis with survey data

As part of a research programme funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant no. ES/S012648/1), researchers from RAND Europe, conducted quantitative analysis based on self-reported survey data from one international banking firm.

Case studies like these can be useful to provide tailored analysis to individual companies about which job quality aspects are more strongly associated with their staff’s mental health and productivity. Other organisations should apply the findings to their own work settings. Yet, the case study might be subject to sampling bias as, e.g. healthier employees are more likely to participate. As such this methodology is only a starting point to find the evidence of what works to improve workplace wellbeing and performance.

The survey, Vitality’s Britain’s Healthiest Workplace (BHW), covers 3,170 survey respondents from organisations in England, Scotland and Wales. Organisations from a wide range of sectors opt-in to participate and then employees take part on a voluntary basis. The self-reported data is collected annually and analysed cross-sectionally. For this analysis we used a pooled sample of waves 2015 to 2019 of the case study organisation (N=1,642).

The data analysis included Ordinary Least Squared regression models with mental health and productivity loss as outcome measures. For the pooled 2015-2019 sample the following models were tested:

- all psychosocial work factors combined;

- interaction terms between work factors and ethnicity.

Suggested citation

Phillips W, Whitmore M and Soffia M. Case Study Evidence: What matters for mental health and productivity in a financial services firm, Briefing, June 2022, What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]