Briefing: Different People, Same Place

Introduction

Better understanding the relationships between individual and place-based community wellbeing

During the Covid-19 pandemic, many people relied on their communities for support more than ever before, and the impact of where we live and work on how we feel became more apparent. The pandemic brought into sharp focus the importance of our communities in how we are doing and a greater urgency to the levelling up agenda which was first proposed by the UK Government prior to the pandemic.

The UK Government’s commitment to levelling up is now set out in a comprehensive White Paper at the heart of which is a recognition that not all places benefit from the same physical and social infrastructure, and people’s sense of pride in and connection to their communities is not equally distributed (1). These features of community are all understood to be aspects of overall “community wellbeing”.

However, as the levelling up agenda brings focus to the differences between places, it is also important to understand the different experiences of people within the same place. While focusing on community wellbeing can help us understand the differences between places, understanding individual wellbeing can bring focus to the different experiences of people within the same place, helping us to better understand the drivers of inequality and disadvantage. Unpacking how individual wellbeing and community wellbeing may be related and how changes in one may lead to changes in the other was at the heart of this project.

This understanding can inform those designing and delivering community based interventions to address key priorities such as increasing wellbeing, supporting levelling up or building community cohesion.

Individual wellbeing

Feeling good and functioning well. Affected by internal and external factors such as the physical and social context of the place where we live and personal relationships.

Community wellbeing

This is how we are doing as a community. It is about how a group of people are doing as a group and goes beyond just adding up the individual wellbeing of the people in that group, to include considerations of how wellbeing is distributed. In this study we defined community wellbeing by thinking about subjective and objective aspects of wellbeing that are of interest at the community level as opposed to at the individual, national or international levels.

National wellbeing

How we’re doing as individuals, communities and as a nation, and how sustainable that

is for the future.

A new model for community and individual wellbeing

In 2021, we conducted an evidence review and expert consultation which drew together the best current understanding of how individual and community wellbeing are related.

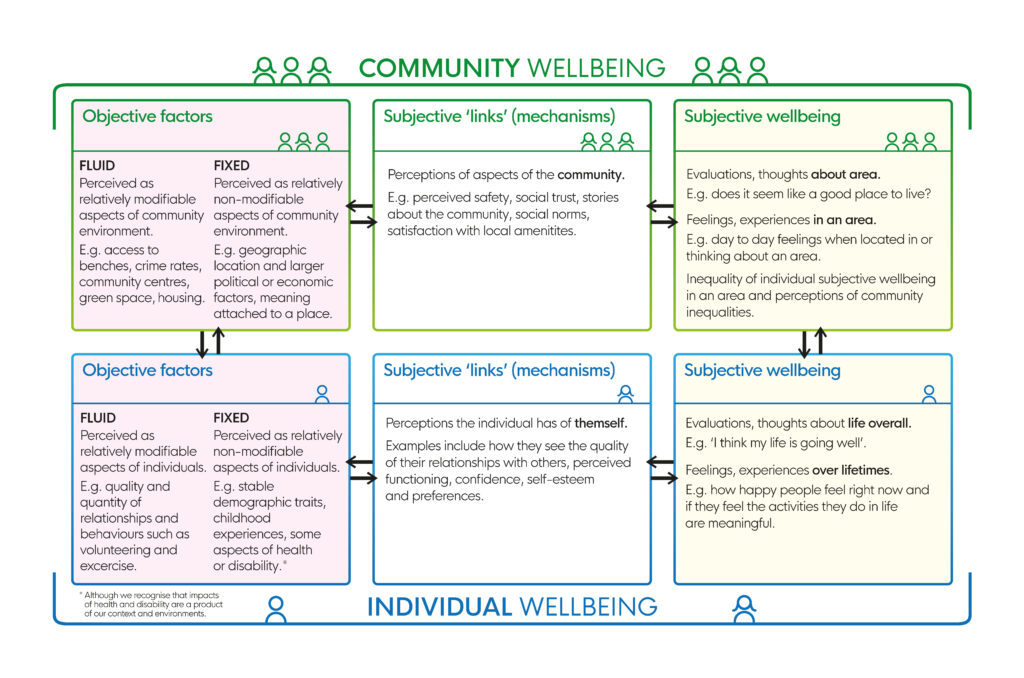

While the work demonstrated that separating individual and community wellbeing is challenging, a simplified model was designed to show how it might be done. Showing the connections between the two, it separates subjective and objective factors at the individual and community levels, as well as the ‘link’ or mechanisms through which these interact. The model can be explored in detail here and the technical report can be found here.

Figure 1: Box model of the relationships between individual and community wellbeing

A tool to improve community and individual wellbeing

People working in communities can draw on data about their local area and evidence from other studies to populate the model in relation to their area of focus.

This can help to:

- Think through the characteristics of a community and its population that are relevant to wellbeing, to identify whether an intervention or change might affect individual or community wellbeing, or both;

- Identify how interventions or changes might impact aspects of wellbeing;

- Consider whether an intervention or changes might affect different people in the same place in different ways, and whether there are groups who might not benefit;

- Construct theories of change for interventions, and develop hypotheses to test through evaluation;

- Support the selection of appropriate measures for evaluation, when used alongside other research on measures of wellbeing at individual and community level;

- Guide co-production of community-level initiatives and interventions.

While the model can support the exploration of these topics, it can’t tell communities what to do. We do not yet have enough robust data at place level to populate the model with all of the factors of interest and more research is needed to establish their interrelationships. That said, our study did start to explore a number of factors and found some interesting results.

Quantitative analysis findings

Through the project, some of the relationships set out in the model were investigated where relevant data was available at Local Authority level. The data came from the ‘Understanding Society’ survey from 2014–16.

This survey asked people about whether they liked living in their neighbourhoods. It also asked questions about volunteering, voting, and socialising with neighbours. This identified some important relationships between objective community factors and both individual and community level wellbeing (3):

Significant associations

- Area-level volunteering rates were associated with both community and individual subjective wellbeing.

- Higher voting rates were associated with better individual subjective wellbeing.

- Higher area-level average income was associated with better individual subjective wellbeing.

- People living in urban areas had worse absolute and relative community subjective wellbeing than those living in rural areas, particularly where voting rates were low.

Walkable assets and wellbeing

Our analysis threw up some unexpected findings which we decided to investigate further. For example, it showed that areas with higher numbers of walkable assets (4) were associated with lower individual and community wellbeing.

This finding seemed counterintuitive, so we undertook further analysis to see if there might be another confounding factor that could explain this relationship. We found that when we controlled for “perceptions of safety” within the community along with other factors these relationships were no longer seen. This suggests that we should not assume that it is the number of walkable assets that is associated with poorer wellbeing.

Different experiences in the same place

The analysis also found some important relationships showing that different people in the same place may be impacted differently by changes in the objective features of their community:

- In more sociable areas, where a higher proportion of people report talking regularly to their neighbours, less sociable people had worse mental wellbeing than sociable people; and less sociable individuals also had worse mental wellbeing in sociable areas than in unsociable areas. In more sociable areas, people aged 50+ had better absolute and relative community subjective wellbeing than aged under 50.

- Unemployment rates were negatively associated with community and individual subjective wellbeing. Higher area-level unemployment was associated with worse community subjective wellbeing for the employed, but not the unemployed. Those aged 50-70 years had better mental wellbeing than those aged less than 50 years when unemployment was relatively low. However, in areas with higher unemployment rates, these age differences fell away.

- While higher area-level income was associated with proportionally better mental wellbeing, this relationship was weaker for households with larger incomes.

“The research showed that some of the subjective factors proposed as ‘links’ were mediating the relationships between objective community factors and subjective individual and community wellbeing.”

It also showed some of these seemed to be more important than others:

- Feeling a sense of belonging was more strongly linked to better subjective wellbeing than perceiving local friendships mattered or that they were able to access local services.

- At the individual-level, perceptions of difficulties managing financially, thinking that finances would be worse in the future, and loneliness were associated with higher odds of low subjective wellbeing.

Qualitative research findings

Through our qualitative interviews and discussions with stakeholders, including people working in local government, policy, academic and the VCSE sector, we found that:

- A lack of representative data at local authority level, and for smaller places (e.g. neighbourhoods or small towns) means that people working in communities don’t have all the information they need to populate the model with data for their places.

- Power sharing and co-production with priority groups are considered to be key mechanisms in addressing the risk that interventions will have negative or unintended consequences for those individuals. There is limited evidence on whether and how co-production affects subjective wellbeing and participation alone is not enough – there are also concerns about who participates and the quality of engagement (5).

- While models can be helpful in provoking new thinking about how different factors within a community interact, we need to avoid implying that there is a single “right” way of improving wellbeing at individual or community level.

Areas for action

The work has highlighted areas of research for further exploration and actions people working in communities to improve wellbeing can take.

These include:

Funders, commissioners and practitioners

- Consider the complex interactions between individual and community level factors, and the potential for the same intervention to affect people with different characteristics, circumstances or experiences in different ways.

- Use the model and findings to think through how their interventions will affect community and individual wellbeing.

- Use the model to consider how their work may fit with and link to other work to improve wellbeing, whether at individual or community level, to help identify potential partners.

- Design evaluations to test the relationships between different objective and subjective factors and the links between them, drawing on the new model and wider guidance around measuring wellbeing.

Researchers

- Keep in mind that the impacts of community interventions may not be seen if data is only collected at local authority level.

- Support work to collect and analyse data across smaller communities, or within the communities that people themselves define as meaningful.

- Undertake further testing of the model, for example at lower administrative levels (e.g. Lower Super Output Areas) or across places as people themselves define them (e.g. individual towns / villages rather than administrative districts), or even across non-geographic communities.

- Test the relationships set out in the model as part of evaluation of individual interventions.

- Continue work to develop and measure a consistent set of local area indicators of individual and community wellbeing – including subjective wellbeing – that are statistically representative at lower geographical and community-levels and easily accessible.

- Continue work to explore the links between community wellbeing and wider national or international contexts, and to map different measures onto the developed models.

References

-

See: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1052706/Levelling_Up_WP_HRES.pdf

-

https://whatworkswellbeing.org/about-wellbeing/what-is-wellbeing/

-

More information about the measures can be found in the technical report.

-

The walkable assets were general/grocery shop, pub, park, library, community centre/hall, sports centre/club, youth centre/ club, health centre/GP, chemist, post office, primary school, secondary school, church/place of worship, public transport links.

-

What Works Centre for Wellbeing (2017) Community wellbeing impacts of co-production in local decision-making. Available at: https://whatworkswellbeing.org/blog/community-wellbeing-impacts-of-co-production-in-local-decision-making/

Suggested citation:

Jopling K, Martin S, Hey N, Hvide L. Better understanding the relationships between individual and place-based community wellbeing, Briefing, March 2022, What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

Also in this project

Downloads

You may also wish to read the blog article on this document.

Downloads

You may also wish to read the blog article on this document.

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]