The Coronavirus pandemic, together with the associated social distancing and lockdown measures, have had a substantial impact on health and public freedom. The immediate and long-term effect on children’s wellbeing is, not surprisingly, a key concern. So what do parents and children themselves feel have been the main effects of the pandemic?

With our annual household wellbeing survey of 2,000 parents and their children (aged 10 to 17) in the field during lockdown (from 28 April to 8 June), we were keen to further understand the experiences of children and their families in the UK, and to also look at children’s wellbeing at this time.

What did parents feel were the immediate and long term impacts?

Parents were asked whether they had experienced a predetermined list of impacts in the last three months. Their responses showed a wide range of practical and financial implications, including; children being at home when they would usually be in education (91%), struggling to obtain food items (65%), and family income being reduced (49%).

In the longer term (next 12 months), the area where the most parents anticipated a negative impact was on the education of children in their household (73%), followed by their family finances (52%).

How well did children feel they had coped?

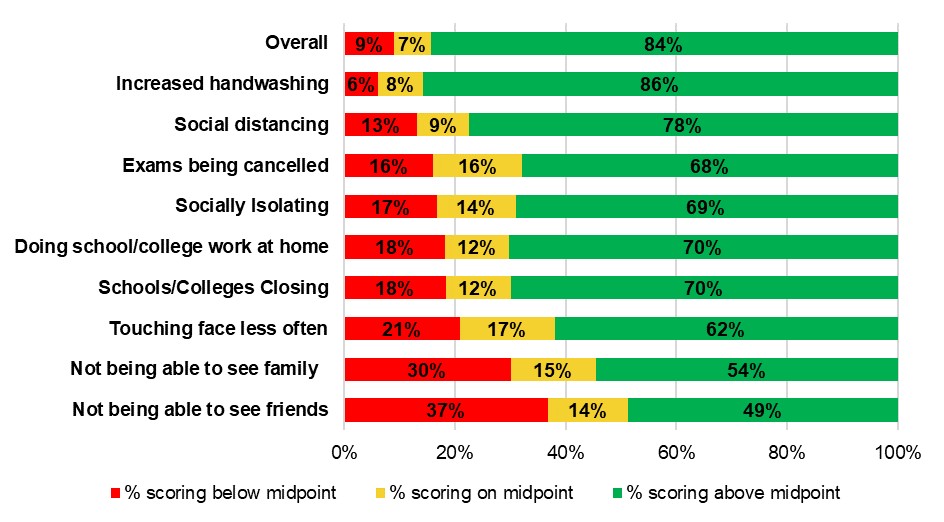

Children were asked to respond on a scale from 0 (not coped very well) to 10 (coped very well) to the question: How well do you think you have coped with the following changes the government put in place because of Coronavirus? (see Figure 1).

Encouragingly, the vast majority felt, overall, they had coped with the changes: 84% scored above the midpoint. 84% of children in UK said overall, they had coped with the changes. The areas where they had coped less well were: with not seeing friends & family. Share on X

Figure 1: Extent to which children (aged 10 to 17) feel they are coping with Coronavirus changes

Source: The Children’s Society’s household survey, Wave 19, April-June 2020, 10 to 17 year olds, United Kingdom. Weighted data.

Note: The above proportions exclude those who responded ‘prefer not to say’. As a result, the N’s vary slightly between items (weighted Ns range from 1,615 for exam cancellations to 1,734 for not seeing friends).

What about children’s wellbeing?

Our annual survey includes several measures of children’s wellbeing. As we do not have data for the period directly before COVID-19 and small changes were made to our survey in 2020, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the impact on children’s wellbeing. We therefore make only broad comparisons to prior results. Key findings were as follows.

- Life Satisfaction: In 2020, a larger proportion than usual – almost one in five children – reported scores below the midpoint (18%), indicating low cognitive well-being. In our previous five surveys, this proportion has ranged from 10% to 13%.

- Good Childhood Index domains: Whereas in the last two year’s children’s responses have suggested they are least happy with their school, the aspect of life with the highest proportion of children scoring below the midpoint in 2020 was Choice. The proportion with low scores for their relationships with friends was also higher than usual (11% in 2020 compared to between 3% and 6% in our previous five surveys), which corresponds with (and may in part be accounted for by) children’s assessments that they felt they were coping less well with being unable to see their friends.

Figure 2: Mean scores (out of 10) and proportion scoring below the midpoint on wellbeing measures

What are the policy implications?

While the vast majority of children seem to have coped to some extent with the changes resulting from Coronavirus, our annual household survey has highlighted key areas for focus to allow those children who may have been affected to bounce back. These include children’s relationships with their friends and wider family, their education, family finances and children’s autonomy.

The Children’s Society continues to call for comprehensive national measurement of children’s subjective wellbeing so that decision makers in national and local government can properly understand how children feel about their lives, identify new trends, target resources properly and better understand outcomes.

The What Works Centre for Wellbeing echoes this need for more understanding around children’s wellbeing. We would like to see the introduction of a formal measurement of the subjective wellbeing of children from Y3 (aged 7-8) upwards on a regular, termly basis.