OECD and wellbeing frameworks: from inspiration to facilitation and collaboration

Governments and social alliances are increasingly adopting high-level wellbeing frameworks to measure and guide their efforts to improve sustainability and wellbeing.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) ‘How’s Life’ analysis and associated framework have inspired and informed several nations’ wellbeing frameworks. These have now been brought together in one place as part of the OECD’s newly launched Knowledge Exchange Platform (KEP).

Here, our Community Wellbeing Lead Stewart Martin discusses wellbeing frameworks, taking us through some examples and exploring how those looking to develop a framework can use the KEP.

In February 2008 economists Jean Paul Fitoussi, Amartya Sen and Joseph Stiglitz were asked by then President of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, to consider the limitations of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and how national progress might otherwise be measured.

The resulting commission’s report contained a series of recommendations, including one calling for a dashboard of indicators:

“At a minimum, in order to measure sustainability, what we need are indicators that inform us about the change in the quantities of the different factors that matter for future well-being”. [Recommendation 11]

The OECD used the report’s recommendations in developing their Framework for Measuring Well-Being and Progress. Both the recommendations and the OECD’s framework have since been used by a number of nations to inform and structure their own wellbeing frameworks, each seeking to identify and measure what is important to their population and inform policy to bring about changes that might improve those outcomes.

Fig 1: Outline of the OECD countries that developed national frameworks, development plans or surveys with a wellbeing focus. 1from the launch event presentation from Romina Boarini, Director WISE –the OECD Centre on Well-Being, Inclusion, Sustainability and Equal Opportunity

Measuring wellbeing around the world

While each framework might have a different name, scale or emphasis, as the Centre for Thriving Places have explored, they appear to share common ‘ingredients’.

Principal among them is their use of indicators or measures that seek to go ‘beyond GDP’ and focus instead on what affects a population’s current and future wellbeing.

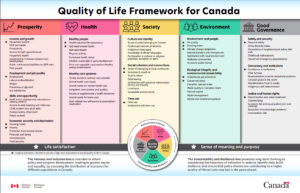

Typically these indicators include drivers such as health, education and employment, alongside measures of subjective personal wellbeing, which are grouped in domains to indicate where priorities may differ slightly. For instance, Australia’s Measuring what matters and Canada’s Quality of Life Hub both have five domains, two of which are the same: health/healthy and prosperity/prosperous. Australia then has sustainable, secure and cohesive where Canada has environment, society and good governance.

Priorities can be different within countries too; New Zealand’s framework seeks to recognise the different conceptions of wellbeing within its population with the He Ara Waiora framework which is designed to help understand Māori perspectives on wellbeing and living standards.

Fig 2: Australia

Fig 3: Canada

Each country is at a different stage in the development and implementation of wellbeing frameworks. For some, this is not their first attempt; Australia’s recently-released framework arrived two decades after its first and is referred to as a “living framework that will continue to evolve and improve over time”, while Ireland’s first report on its framework referred to pursuing “an iterative approach to allow for its evolution”.

Wales are arguably further than most in the implementation of their framework and not only have wellbeing indicators but also associated law, a new Future Generations Commissioner, and strategy.

These frameworks are subject to change and development over time, just as their populations’ priorities might change.

Scotland has a National Performance Framework and has just opened a consultation on a Wellbeing and Sustainable Development Bill, while Ireland seeks to ‘understand life in Ireland’. We contributed our expertise to The Office for National Statistics’ (ONS)’s review of the UK Measures of National Well-being when the number of indicators in its dashboard increased from 44 to 60, while Italy utilises more than 150.

Fig 4: Seven connected wellbeing goals in Wales

Fig 5: Ireland

Fig 6: Scotland (from NPF presentation)

Knowledge Exchange Platform

To promote learning between and beyond the countries that have produced wellbeing frameworks, the OECD recently launched its new Knowledge Exchange Platform on Well-being Metrics and Policy Practice (KEP).

Users can access associated documents and links to each framework, as well as policy context and key outcome information. The OECD also plans to:

- Hold Knowledge Exchange Workshops

- Support informal peer networking

- Develop case studies, methodological development and policy advice

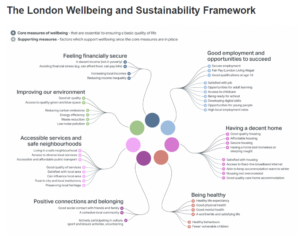

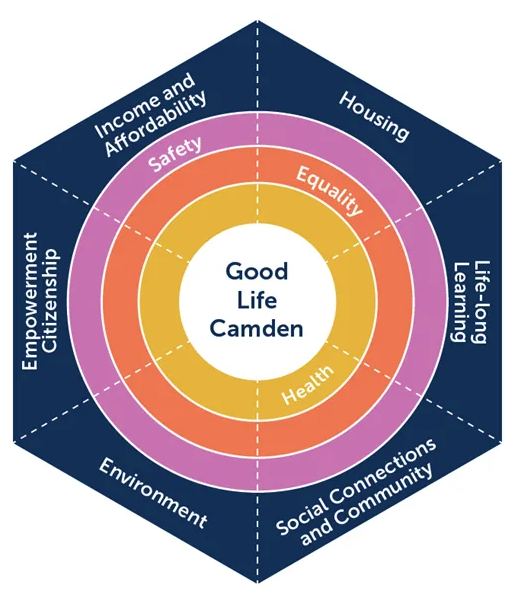

In due course, sub-national wellbeing frameworks will be added. This might include local examples from England:

- London Wellbeing and Sustainability Measure

- Camden’s Good Life Project

- North of Tyne’s Wellbeing Framework

- Walsall’s Wellbeing Outcomes Framework

Fig 7: London

Fig 8: Camden

Fig 9: North of Tyne

Fig 10: Walsall

What next?

There is a growing body of evidence on what works in implementing wellbeing frameworks, but it is far from established and there is currently no blueprint model. There are also concerns about an implementation gap where frameworks are produced but subsequent actions are limited and outcomes remain largely unaffected.

We recognised similar challenges in our work with local authorities and sought to address these when recommending how to implement health and wellbeing strategies. The Green Book and its supplementary guidance also aims to incorporate wellbeing valuation across organisations in a clear and consistent way.

The OECD’s new platform seeks to help users learn from others and strengthen their approaches, to close the implementation gap, ensure frameworks are effective and wellbeing is at the heart of policy. There is much to be learnt.

What you can do:

- Explore the national wellbeing frameworks in more detail using the links provided

- Consider whether a Knowledge Exchange Workshop may be of use to you

- Engage with the OECD WISE Centre on the KEP at wellbeing@oecd.org