Review refresh: Places, spaces, and social connections

Downloads

The quick read

In 2018 we published a review of the changes made to community places and spaces that are designed to boost social relations and individual and community wellbeing.

Five years on, we have refreshed the review demonstrating how the evidence base has grown. Its findings were combined with those of the original review.

We found:

- Strong evidence for community hubs and community development improving social relations, individual and community wellbeing (evidence was moderate in 2018 review)

- Many interventions brought about both positive and negative impacts on wellbeing – for instance, local events can improve community wellbeing for many but have a detrimental impact on those they exclude (as also found in Different People, Same Place).

- The number of studies in this evidence base has doubled in five years. (51 included papers from 2017-2022; 51 included studies from 1997-2016).

The refresh provides greater differentiation between types of interventions and their impact on wellbeing and social relations.

The refresh was conducted by Leeds Beckett University in partnership with the University of Liverpool, and funded by the National Lottery Community Fund.

Background

In 2018 we published our original systematic review of changes made to community places and spaces that were designed to boost social relations and individual and community wellbeing.

The review looked at three key questions:

- How effective are these changes?

- What factors affect effectiveness?

- What are people’s subjective experiences?

It found evidence that a range of approaches to changing community infrastructure can lead to improved social relations and community wellbeing.

Limitations

Of the 51 included studies from 1997 – 2017, few were deemed high quality. Almost all the evidence was limited to a categorisation of ‘promising’.

Recommendations

The review called for improved evaluations of interventions implemented in the UK (or that may be implemented in the UK), and highlighted particular gaps in the evidence for:

- Events

- Placemaking

- Alternative use of space

- Urban regeneration

- Community development

In 2021 we undertook a practice-based case study synthesis of evidence on how green spaces and community hubs can enhance wellbeing in place. The response to this, coupled with the original research team’s continued activity in and knowledge of the evidence base, led us to the 2023 refresh.

The study

What we did

As this was a refresh of the evidence, the same search parameters as the original 2018 review were used. See our registration of the search made on PROSPERO.

The refresh was undertaken by the same research team who conducted the original review, led by Leeds Beckett University working in partnership with the University of Liverpool. As with the original review, What Works Centre for Wellbeing hosted a call for evidence.

The concepts of community wellbeing, community infrastructure and social relations, and the definitions of eight intervention types from the 2018 review were maintained for the refresh.

See below for definitions.

Community wellbeing

Community wellbeing is about being well together. Our working definition for this review is: ‘the combination of social, economic, environmental, cultural, and political conditions identified by individuals and their communities as essential for them to flourish and fulfil their potential.’ (Wiseman and Brasher 2008: 358)

Community infrastructure

Community infrastructure is defined as:

- Public places and ‘bumping’ places designed for people to meet, including streets, squares, parks, play areas, village halls and community centres.

- Places where people meet informally or are used as meeting places in addition to their primary role, such as cafes, pubs, libraries, schools and churches.

- Services that can facilitate access to places to meet, including urban design, landscape architecture and public art, transport, public health organisations, subsidised housing sites, and bus routes.

Social relations

Social relations underpin many ideas, such as social capital and sense of community. It covers a wide variety of human interactions, interconnections, and exchanges between human beings and the physical and social environment. The connections with people around us are an important determinant of individual and community wellbeing, leading to social values such as trust in others and social cooperation. (Evans, 2015)

Community hubs – community centres or community anchor organisations focused on health and wellbeing that can either be locality-based or work as a network. They typically provide activities and services open to the wider community that address health or the wider determinants of health.

Events – temporary events that take place at a community level, such as festivals, markets, art events, street parties, concerts. Events can range from a one-off activity to a regular, sometimes weekly, occurrence.

Neighbourhood design – the scale, form or function of buildings and open space.

Green and blue space – any natural green space: parks, woodland, gardens; or blue space: rivers, canals, or the coast.

Place-making – the role of arts, culture and heritage in helping to shape the places where we live.

Alternative use of space – temporary changes to the way that people interact with a space, such as closure of streets for children to play, public art installations or a ‘pop-up park’.

Urban regeneration – the process of improving derelict or dilapidated districts of a city, typically through redevelopment.

Community development – a long-term value-based process which aims to address imbalances in power and bring about change founded on social justice, equality and inclusion.

The focus of both the original review and the refresh was on interventions operating at the neighbourhood level (rather than city or national). Virtual spaces were beyond the scope.

Making the cut

- Studies initially identified N= 28,619

- Full text articles assessed for eligibility N= 328

- Separate studies included in the final refresh N= 51

- Total number of studies included in overall analysis across both reviews N=102

What did we find?

The full report for the refresh incorporates the studies and findings from the original 2018 review, superseding it.

The key findings listed below are derived from all 102 included studies across 1997-2022.

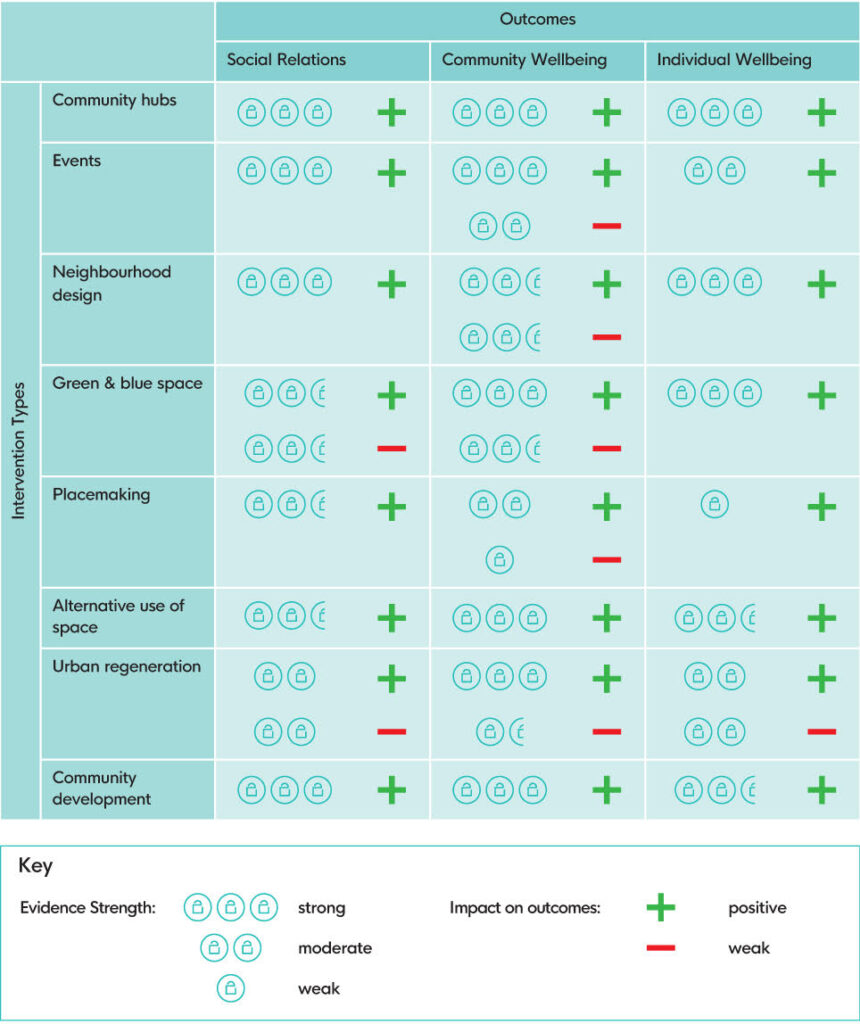

The table summarises findings. More details on each intervention type are available below.

Community hubs

- There is strong evidence community hubs increase social networks

- There is moderate evidence community hubs promote social cohesion and create bonding and bridging social capital.

- There is weak evidence (from one study) of both negative and positive effects on social cohesion of a church-based hub.

- There is moderate evidence community hubs create a sense of belonging within communities , a sense of pride in the wider community, increases in community empowerment, civic participation and improvements in the social determinants of health.

- There is strong evidence that community hubs improve mental health and wellbeing.

- There is moderate evidence that community hubs support individual empowerment by fostering a sense of control.

Community events

- There is moderate to strong evidence that community events can expand social networks, can boost social cohesion by mixing age or ethnic groups, boost bonding and bridging social capital.

- There is moderate to strong evidence that community events may have potentially negative effects on social capital (for instance if too great an emphasis was felt to be placed on attracting people from outside the local community).

- There is strong evidence community events increase sense of belonging or pride through shared identity and contribute to community empowerment.

- There is moderate to strong evidence that community events contribute to civic participation and knowledge and cultural exchange.

- There is moderate evidence that community events improve the social determinants of health.

- There is moderate evidence that community events can lead to a potential loss of shared identity, gentrification and/or physical or perceived exclusion of local residents from events.

- There is moderate to strong evidence that community events can increase skills and knowledge

- There is moderate evidence that community events can improve mental health and wellbeing, hedonic wellbeing, and improve employability through volunteering.

Neighbourhood design

- There is strong evidence that neighbourhood design interventions can improve social networks.

- There is moderate evidence that neighbourhood design interventions can improve social cohesion, as well as weak evidence that it has no effect.

- There is moderate to weak evidence that neighbourhood design interventions have a positive impact on social capital.

- There is moderate to strong evidence that neighbourhood design interventions can boost sense of pride, belonging, ownership and empowerment, and improve social determinants of health.

- There is moderate evidence that neighbourhood design interventions can boost civic participation.

- There is weak to moderate evidence that neighbourhood design interventions can have both positive and negative impacts upon sense of safety.

- There is strong evidence of negative perceptions of a transfer of ‘problems’ to other areas.

- There is moderate to strong evidence that neighbourhood design intervention can lead to negative issues with gentrification.

- There is strong evidence neighbourhood design interventions can improve physical health or physical activity

- There is moderate to strong evidence that neighbourhood design interventions can have a positive impact on mental health and wellbeing, but also weak evidence that it can have a negative impact.

- There is moderate evidence that neighbourhood design interventions can boost skills and knowledge, social connections and sense of belonging.

Green and blue space

- There is strong evidence green and blue space interventions boost social cohesion

- There is moderate to strong evidence green and blue space interventions boost social capital.

- There is moderate to strong evidence green and blue space interventions can have both positive and negative impacts upon social interactions.

- There is moderate to strong evidence green and blue space interventions can have a negative impact due to perceived exclusion.

- There is strong evidence that green and blue space interventions can boost sense of belonging and pride.

- There is moderate to strong evidence green and blue space interventions can boost empowerment.

- There is strong evidence green and blue space interventions can have a positive impact upon the social determinants of health, but also moderate to strong evidence of negative impacts.

- There is weak evidence green and blue space interventions can boost civic participation.

- There is moderate to strong evidence green and blue space interventions can have negative impacts on community wellbeing due to gentrification and the contested use of space.

- There is strong evidence green and blue space interventions boost physical activity, empowerment and improve skills and knowledge.

- There is moderate to strong evidence green and blue space interventions boost mental wellbeing.

- There is weak evidence that green and blue space interventions support connection to nature.

- There is moderate evidence green and blue space interventions can lead to unequally distributed benefits.

Placemaking

- There is moderate evidence placemaking interventions boost social interaction.

- There is moderate evidence placemaking interventions have a positive impact upon social cohesion, but also weak evidence that it can have a negative impact.

- There is weak evidence placemaking interventions can boost social capital.

- There is moderate evidence placemaking interventions can boost sense of belonging and pride and the social determinants of health.

- There is weak evidence placemaking interventions boost civic participation.

- There is weak evidence placemaking interventions have a negative impact upon community wellbeing due to gentrification.

- There is weak evidence placemaking interventions can have positive impacts upon physical activity, empowerment, knowledge and skills, and economic outcomes.

- There is weak evidence placemaking interventions can lead to unequally distributed benefits.

Alternative use of space

- There is moderate to strong evidence alternative use of spaces can boost social cohesion and social capital.

- There is moderate evidence alternative use of spaces can boost social interaction.

- There is moderate to strong evidence alternative use of spaces can have a positive impact upon civic participation and reduce crime or the fear of crime.

- There is moderate evidence alternative use of spaces can have a positive impact on sense of community and identity, belonging and pride, as well as the social determinants of health.

- There is moderate to strong evidence alternative use of spaces can have positive impacts on physical activity and mental wellbeing.

- There is moderate evidence alternative use of spaces can have positive impacts on skills and knowledge.

- There is weak to moderate evidence alternative use of spaces can boost hedonic wellbeing.

Urban regeneration

- There is moderate evidence urban regeneration can have a positive impact on social interactions.

- There is moderate to weak evidence urban regeneration can have a positive impact on social capital, but also moderate evidence it can have negative impacts.

- There is strong evidence urban regeneration can have a positive impact on crime or the fear of crime, but also weak evidence it can have a negative impact.

- There is moderate to strong evidence urban regeneration can have a positive impact on the social determinants of health, but also weak evidence of a negative impact.

- There is weak evidence urban regeneration can have a positive impact on sense of belonging and pride, but also weak evidence it can have a negative impact.

- There is weak evidence urban regeneration can have a positive impact on civic participation.

- There is moderate evidence urban regeneration can have a positive impact on skills and knowledge.

- There is moderate to weak evidence urban regeneration can have a positive impact on mental wellbeing, but also moderate evidence it can have a negative impact.

- There is weak evidence urban regeneration can have a positive impact on physical activity and mental health.

- There is moderate evidence urban regeneration can have a negative impact on empowerment.

Community empowerment

- There is strong evidence community development has a positive impact on social interactions

- There is moderate to strong evidence community development has a positive impact on social cohesion, and social capital.

- There is moderate to strong evidence community development has a positive impact on community empowerment, sense of belonging, pride and community identity, as well as the social determinants of health.

- There is weak evidence community development has a negative impact on community wellbeing due to gentrification.

- There is moderate to strong evidence community development has a positive impact on physical activity.

- There is moderate evidence community development has a positive impact on knowledge and skills.

- There is weak evidence community development has a positive impact on mental wellbeing and empowerment.

Covid-19

There was limited evidence relating to the pandemic, which could be because relevant studies are still yet to be published and because online interventions were out of the scope of this refresh.

Those that were included found:

- Green and blue spaces support social relations, individual and community wellbeing, although the closure of some facilities meant some spaces became problematic to use (e.g. play parks and public toilets).

- Some spaces became [more] contested and/or overcrowded as a result of covid restrictions.

- Some volunteering opportunities, and the benefits derived from them, ceased.

- Communities were quick to respond in adapting interventions, providing them virtually or in a socially distanced manner, as well as pivoting to provide alternative services.

- Some improvements arising from interventions were lost due to lockdown restrictions.

Research implications

In 2018, the review found good quality evidence was lacking in five of the eight theme areas. Now the evidence base is much stronger. An evidence gap remains for high-quality research on placemaking.

There are also gaps in the evidence comparing rural and urban settings, as well as interventions made during the pandemic (although this could be due a publication lag). Those that did refer to the pandemic confirmed that it was a disruptive event for communities and community-based organisations.

Recommendations for action

For researchers and research funders

- Further research into place and space interventions designed to boost social relations and community in rural settings.

- More methodologically robust studies of placemaking interventions, using larger sample sizes and consistent concepts and measures.

- A review of interventions to boost social relations and community wellbeing in virtual or hybrid spaces.

- Further research to understand the reach of wellbeing interventions within communities, including with individuals and groups that do not participate in them.

- Further research should use appropriate methodologies to understand more explicitly what works, for whom, and in what context.

For policy makers, commissioners and funders

- The body of evidence is much stronger than in 2018 and provides a menu of possible wellbeing interventions linked to positive outcomes.

- Use inclusive engagement to ensure community wellbeing interventions have positive outcomes for a diverse range of groups.

- Carry out an impact assessment to give attention to the potential negative or unequal impacts of any interventions.

- Articulate a broad range of outcomes from interventions that build social relations in places or spaces within programme and funding specifications to help ensure they are properly captured.

- Support commissioned interventions with resources for robust evaluation, especially in rural areas.

For practitioners

- The body of evidence is much stronger than in 2018 and provides a menu of possible wellbeing interventions linked to positive outcomes for practitioners to consider.

- Use a flexible approach, allowing activities and volunteer involvement to evolve over time.

- Develop a friendly and safe environment to make users feel welcome and included.

- Pay attention to inclusion and reducing barriers to ensure that activities are accessible.

- Consider the transferability of interventions and whether local adaptations should be made (e.g. urban to rural).

- Directly address the emerging issue of contested space, in relation to different communities of interest, age groups and newer vs more established residents, as well as differing priorities regarding making outdoor spaces accessible and keeping the natural biodiversity of wild spaces.

Suggested citation

Martin, S. and Bignall-Donnelly, R. Review refresh: Places, spaces and social connections. Briefing, 2 February 2023, What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

Lead image credit: Photo by Jonny Gios via Unsplash

Further resources

Explore the project page.

- The quick read

- Background

- The study

- What did we find?

- Community hubs

- Community events

- Neighbourhood design

- Green and blue space

- Placemaking

- Alternative use of space

- Urban regeneration

- Community empowerment

- Covid-19

- Research implications

- Recommendations for action

- Suggested citation

- Further resources

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]