Tackling Loneliness: Review of Reviews

Downloads

Intro

Why is Loneliness an Issue?

Loneliness is an experience that most of us will encounter at some point in our lives, either momentarily or as a more prolonged experience because of events like the loss of a parent or friend. Being lonely can become a serious issue when it becomes a day-to-day reality as it affects both our health and wellbeing, and the way we function in our communities.

What is Loneliness?

Loneliness occurs when there is a gap between our actual and desired social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, 1981), and when the quality or quantity of these relationships does not meet our expectations. Loneliness is different from social isolation. Social isolation is objective and based on the number of people in our social networks. Socially isolated people may have few or no social ties. In comparison, loneliness is subjective and experienced.

Who’s affected?

Until recently, becoming chronically lonely (feeling lonely all or most of the time31) was only associated with older age. However, we know that loneliness can be a barrier to wellbeing at any age.

Academics, practitioners and policy-makers have become interested in understanding the risks of being lonely in diverse population groups33, 32, 37, 44 and whether transitions we go through at different life stages may be triggers for loneliness

What evidence was used?

This briefing is based on a systematic review of evidence reviews,1 which intended to answer the question: What is the effectiveness of interventions to alleviate loneliness in people of all ages across the life-course?

What studies were included?

The review of reviews begins the process of mapping the evidence base and identifying the potential gaps and areas to focus on. To do this, published studies were only included in the review of reviews if they:

- used controlled designs – the choice to use the most robust design possible allowed us to minimise bias and issues of methodological diversity connected with the variegated nature of the interventions, settings and populations. This allowed us to assess the effectiveness of different approaches and maximise the generalisability of results for policy recommendations.

- measured loneliness and reported on this outcome.

We sifted through 364 reviews

This review covers all published reviews on loneliness conducted in the past 10 years

and unpublished reports since 2008 (14 academic reviews and 14 unpublished papers from the UK grey literature).

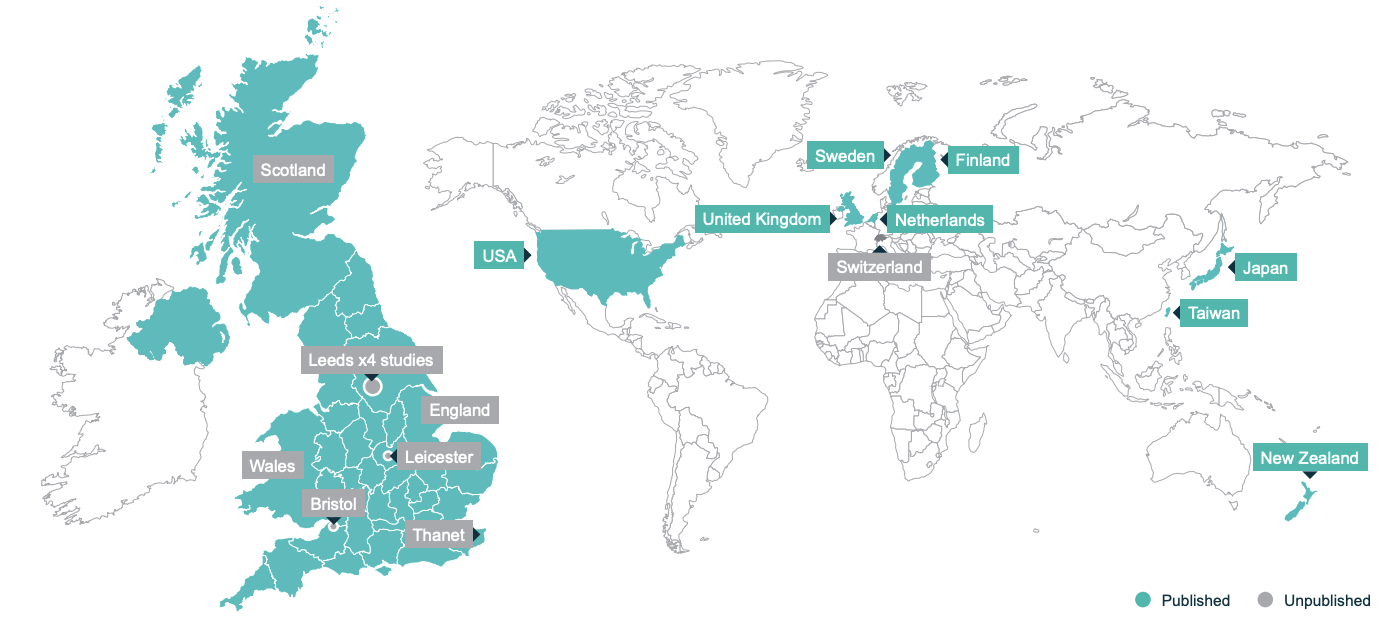

This briefing includes findings from the USA, the Netherlands, Finland, Japan, New Zealand, Sweden, Taiwan and the UK, and unpublished papers from England, Wales, Scotland and Switzerland.

The evidence we found on loneliness is focused on older adults. Therefore, the findings

in this briefing are based on participants of 55 years and over.

What are the key findings?

State of the evidence

- There is a need for greater clarity on the concept of loneliness and how it differs from social isolation, for researchers and practitioners. The terms loneliness and social isolation were often used interchangeably within the reviews. Loneliness was often not the primary outcome in the published studies and was measured alongside other related concepts like social isolation, social support, social networks, and health outcomes including anxiety and depression.

- There is a great deal of variability in the evidence base regarding the type of measure and the way in which they’ve been used. Many of the studies analysed used different measures of loneliness, or different versions of the same scale and most importantly, the results weren’t reported in a consistent manner which hinders comparability of results.

- We know much less about what interventions are effective for reducing loneliness at earlier life stages.32 The findings in this briefing are based on participants of 55 years and over, as evidence on other age groups did not meet the inclusion criteria for the review. The lack of evidence specific to young and mid-life adults is a clear gap in our knowledge base and reflects the conceptualisation of loneliness as a problem of later life. The lack of diversity in the published studies does not reflect the current (and future) socio-demographic profile of this population but it highlights an opportunity for greater conceptual clarity and future research.

- Few of the studies reported the details about how interventions worked to alleviate loneliness in different population groups, and what processes are needed for a successful intervention. However, some unpublished evaluations explored loneliness interventions for different groups including LGBT groups, men, and vulnerable adults, are included, with some positive findings reported in reducing loneliness in these groups.

- Building on existing community assets and networks to reduce loneliness was a key feature in a number of the interventions in the unpublished studies. These interventions used an Asset-Based Community Development approach to tailor services and reconnect people to their community.27, 19, 26 The effectiveness of this approach wasn’t stated in the included studies and more comparative research with alternative approaches is needed.

- Clearer understanding is needed on how loneliness relates to other mediating factors, such as social support and social connections.

- More large-scale, controlled study designs are required to draw any solid conclusions about what approaches are most effective, for which groups of people, in what settings and for how long.

Key Findings

- The evidence illustrates that there is no one-size-fit-all approach to alleviating loneliness in older population groups and that tailored approaches are more likely to reduce loneliness.

- It is not yet clear what approaches are effective in alleviating loneliness but several mechanisms for reducing loneliness were identified in the unpublished literature, including:

- Tailoring interventions to the needs of people for whom they are designed

- Developing approaches which avoid stigma or reinforce isolation

- Supporting meaningful relationships

- The evidence about the effectiveness of group-based interventions versus those delivered in one-to-one settings was inconclusive.

- In one published and one unpublished study it was reported that people with high levels of loneliness benefitted the most from loneliness interventions, compared to people who are less lonely.8,26 However, more robust evidence is needed to support this finding.

Interventions and approaches

The review found that different approaches are being used to alleviate loneliness in older adults. Interventions are being delivered in care homes and other forms residential accommodation or out in the community and in people’s homes.

There was no evidence of approaches doing any harm. However, there was a suggestion that some technology-based approaches are not suitable for everyone and could reinforce a sense of social isolation without a proper assessment of people’s capacity to use technical equipment.4 Few studies compared types of delivery. One study did identify that social groups and activities were the primary mechanisms for reconnecting lonely people and facilitating new connections.27 The role of the group and shared activities is a mechanism that should be looked at in more detail.

“Suddenly I have new friends with common interests, have somewhere to go, and am doing things again. It’s literally changed my life around.”

Leisure activities

- Indoor gardening in care settings was found to reduce loneliness 3, 5 and outdoor gardening in the community was offered as one element of a mixed intervention which was found to be largely effective.19

- Music wasn’t included in any of the published reviews as an intervention to alleviate loneliness. However, one unpublished study conducted in Switzerland included a music intervention targeting nursing home residents. The programme was tailored to what music the residents’ liked and they then took part in a 10-week programme involving group music-making and singing.25 Qualitative data revealed a decrease in loneliness amongst participants but more research is needed to assess the relationship between music interventions and loneliness.

- Physical activities included supervised walking, or resistance exercise training or a mix of the two (swimming and Tai Chi exercises). Sometimes social and recreational activities took place alongside physical activities.12 Physical activity did not appear to be effective for reducing loneliness.

Therapies

- Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT) is used to increase perceived social support and social interaction. In the review, AAT ranged from placing caged birds in residents’ rooms, to interactions with animals one to one, or in groups of two to four people.3, 8, 32, 10 There was some evidence that the loneliest people benefited the most from AAT.8 Socially-assisted robot technology and companion robot animals were tested in care homes.2, 6, 32, 10, 11, 15 In some cases, companion robot animals were incorporated into group activities and discussions.6 The effects of these technologies were mixed as some studies found an effect and similar ones didn’t and there are methodological issues with some of the studies explored.

- Reminiscence therapy draws on participants’ life experiences to reduce depression and negative feelings, and improve comprehension. It was delivered through weekly group settings and one study demonstrated reduced levels of loneliness after three months.3

- Cognitive enhancement involves educating people about the brain in order to stimulate memory, which takes place alongside activities designed to facilitate social interactions and enhance social networks.3 One study conducted in the US didn’t find any significant reduction in loneliness scores for people in care facilities.

- In one study, an eight-week humour therapy programme involving fun and creative group sessions, development of happy portfolios, telling jokes and laughing exercises was found to be effective in reducing loneliness.5

Social and community interventions

- Social and community interventions were used to reconnect people to their communities and networks. One eight-week programme in Tokyo involved community gatekeepers who worked with people in groups for two hours every two weeks to improve community knowledge and encourage networking8 and it was found to be effective.

- Community sharing principles were used in different ways to design interventions in the unpublished studies. In one home sharing project ‘householders’ were brought together with younger ‘housesharers’ that needed affordable housing. The houseshares provide companionship and up to ten hours a week of low-level support to the householder. No data was reported regarding the effectiveness of the intervention but qualitative interviews revealed a positive effect. Hence, companionship was seen as an important mechanism for reducing loneliness.28

- Another project organised shared meals at local restaurants and pubs to bring single people together. Meals took place at different venues and times, some during evenings and weekends, with tables hosted by a volunteer. Meaningful relationships were developed out of contact in these intimate settings of 6-8 people, compared to larger coffee mornings that some participants had attended before and found more daunting.20

- Advice and signposting services were commonly used to reconnect people to their communities.16, 17, 21, 30 One Community Webs project included link-workers who were based in GP centres. They used signposting and offered support to people in order to help equip them with the skills to locate opportunities for taking part in community activity. The positive impacts of this approach on loneliness were reported and were sustained after three months.17

- Using person-centred strategies to tailor support and signposting into community activities were found to be important mechanisms for reducing loneliness.27, 16, 17

“I value the company the most, because I was on my own, had no one to talk to and you get bored when you’re on your own. Now that I’ve got Lauren [homesharer], I’ve got someone to talk to.”

Educational approaches

Different educational approaches were used to teach people new skills and build confidence when forming social relationships.

- Relationship training focussed on teaching people the skills necessary to form new friendships and /or improve their current ones. One study taught care receivers how to optimise their relationship with their caregivers and it was found to be effective in reducing loneliness.5 However, a telephone crisis programme that included a tailored service arrangement and supportive therapy such as building communication skills, and, a friendship enrichment programme for older women, were found not to be effective.5, 10

- Other activities included a psychosocial element that consisted in social skills practice and facilitation of social interactions. Most were delivered in group settings both in care homes and in people’s homes. None were found to be effective but some showed a promising trend. 5, 7

- Self management approaches aimed at teaching self-esteem and self-care, and often involved practicing friendship skills and mindfulness. Published studies in this area showed a positive effect of these type of interventions on loneliness.5, 7

- Skills training helps people to learn how to use the internet, social media and specific devices (e.g. computer). Some took place in people’s homes, in care homes individually or in small groups. It was unclear whether skills training helped in reducing loneliness.3,4,7 In some interventions, videoconferencing was used to facilitate connections between older people and their family members who did not live close by and it was shown to have a positive effect in reducing loneliness at one week and three months post implementation. 3, 4, 10

Befriending

- Befriending was the most common approach reviewed and was reported in 25 unpublished projects and identified by several published reviews.24, 19, 4, 5, 6, 7, 18, 30, 28, 11, 13, 12

- Befriending is a form of companionship that is provided regularly, often by a volunteer and traditionally one-to-one.13 However, a broad range of activities were described as befriending, including supporting individuals to re-engage with their local networks and group befriending involving shared activities in the community.

Befriending is a complex intervention, that when effective can help develop meaningful relationships and was found to reduce stigma in one unpublished study. 24 However, the evidence on the effectiveness of befriending on loneliness in the review was not conclusive. One systematic review and meta-analysis of befriending interventions found no significant benefit of befriending on loneliness.13 The authors of that review suggest that a model should be developed to help researchers and practitioners to better understand the effects of befriending on loneliness and what makes up this complex intervention.

System-wide activities

- System wide activities were used as a vehicle to change the culture of care in nursing homes and the community from an institutional, medical model to a more person-centred approach. Both the 4R programmes ‘reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation, and restorative’ and the Eden Alternative focussed on empowering the recipients of care both in their homes and in care facilities to in recognising what they are able to do and engaging them in activities. None of them were found to be effective for loneliness.14, 3

“I knew people by name or in passing, but now I feel I have much deeper connections as a result of spending time with small groups on the shared tables.”

How can we build on this evidence?

Develop a conceptual and theoretical framework for loneliness

Researchers, practitioners and other stakeholders should work together on a framework for understanding loneliness, its pathways and other related and mediating factors. The lack of conceptual clarity surrounding loneliness was evident in the review. Loneliness was often used interchangeably with other terms and measured alongside factors such as social isolation, social support, social networks. This makes it hard to understand where approaches are having the most effect and on what factors.

Understanding how other factors relate to loneliness and how they relate to wellbeing will also be helpful for a wide range of projects and policies. For example, how do social isolation, social connection, social integration, social support, neighbourliness, social trust, quality of relationships, sense of belonging, perceived quality of society inter-relate and how do they relate to wellbeing and loneliness?

Furthermore, it is possible that interventions aimed at younger age groups or aimed at preventing loneliness might focus on measuring concepts like resilience and social connections, rather than loneliness itself. This might explain why this review did not pick up research conducted with younger age groups, as measuring loneliness, rather than resilience, was a key inclusion criteria.

A framework would support the measurement and testing of loneliness interventions and would help us to better understand how the diverse range of loneliness approaches that currently exist relate to different aspects of loneliness and wellbeing. It would also help with understanding how the evidence in this review fits in with interventions taking place at other life stages or approaches that seek to prevent loneliness and improve wellbeing.

Use and report on an appropriate set of loneliness measures

Researchers should be sure to report the loneliness scale and the version of the scale that they are using to measure loneliness, as well as consistently reporting the effect sizes along with averages and adopt a shared threshold. This will help others to learn from research and replicate studies on a larger scale. It is also essential to align on population-level measures. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) is working with a panel of experts to recommend national indicators of loneliness for use on major studies. Such measures are needed to encourage greater consistency in how we measure loneliness and better comparability of findings.

This will also be very important for building a coherent evidence base, which will enable better understanding of which interventions work most effectively to prevent or alleviate loneliness for different groups of people. Alongside this, the What Works Centre for Wellbeing (WWCW) is working on a guidance on the different loneliness measures and their suitability of use in different settings.

A framework would support the measurement and testing of loneliness interventions and would help us to better understand how the diverse range of loneliness approaches that currently exist relate to different aspects of loneliness and wellbeing.

Improve, build up and track progress of the evidence base

Look in more detail at how approaches work in different settings and for different groups. Some approaches used one-to-one methods and some focused on group strategies, but few compared the two and it is therefore not clear which might be better suited to particular population groups. Other delivery modes were not compared such as volunteer versus professionally led, digital versus face-to-face and community versus care home settings.

The mode of delivery may influence the effectiveness of approaches and could also also have cost implications. We need to understand more about different modes of delivery in approaches to alleviating loneliness and conduct high quality comparative studies. It’s important also to include cost information to allow for cost effectiveness assessment and comparisons.

The studies in the review were overwhelming focused on older adults. But we know that loneliness can affect people of all ages and may be experienced differently by diverse population groups. More high quality research is needed to address loneliness in different groups. In general, where there are gaps in the evidence, it will be important to start building knowledge at the appropriate stage e.g. smaller scale studies that support the development, manualisation and implementation of programmes, projects, policies and approaches.

Mapping all the practice approaches will further identify where research and evaluation opportunities exist.

Projects and evaluations are happening all the time. Finding a mechanism and necessary partnerships to bring together findings from academia as well as policy and project evaluations into one place as they happen can allow:

- sectors to learn together

- spot what is genuinely innovative

- reduce duplication or small scale studies of things that are already well known

- allow for studies of greater scale by finding partners doing similar activities in different areas

- connect researchers with practice

Related articles

You might be interested in this read

Downloads

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]