This summary will look at inequalities based on gender, age, ethnicity and socio-economic status (including education and income), before considering some other factors that have emerged out of the database.

Gender

Overall, it’s clear that the pandemic has had a larger impact on the subjective wellbeing of females, rather than males. Is this a change to wellbeing inequality? It depends on the measures used and what is controlled for.

Before the pandemic, men and women had almost identical average life satisfaction and women a higher sense of purpose, slightly lower happiness and considerably more anxiety. When we control for religiosity and employment there are no differences between men and women in happiness and women have higher life satisfaction. So, depending on which subjective wellbeing question is considered and whether these factors are controlled for, the difference between men and women can be seen as having increased or decreased.

A mixed methods study helps explain why women’s wellbeing has suffered more, and points to additional childcare and home-schooling responsibilities.

Meanwhile two studies looked at differences between boys and girls. Although one early study found that boys were more affected by lockdown than girls, a later one reported that girls had more anxiety about going back to school after the long break in September 2020.

Age

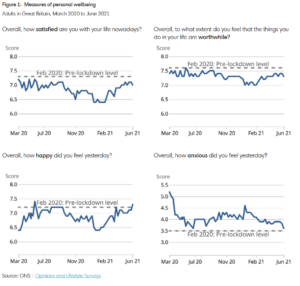

Early results on the impacts of the pandemic and lockdown on subjective wellbeing suggested that older people were taking the brunt of the hit. Using data from YouGov’s mood tracker, a study by the University of Cambridge found that, up until June 2020, people 65 and over suffered a greater loss of wellbeing than younger age groups.

However, more recent analysis suggests that the picture is more complex. Using data from the APS up until September 2020, analyses by the What Works Centre for Wellbeing indicate that, whilst the age group 65-74 were indeed harder hit than other age groups, the age group 75-84 were less hard hit in terms of life satisfaction, although they showed the hardest hit in their sense of purpose. Meanwhile, young people aged 20-34 were also amongst the hardest hit by the pandemic especially as the pandemic progressed.

A couple of other studies provide some explanation for the potentially greater negative impact of the pandemic on young people. The ONS identify boredom and loneliness as factors that are particularly important in explaining low wellbeing amongst young people. Meanwhile, the RSPH and Mental Health Foundation report greater anxiety about the future and less hope amongst younger people. The Mental Health Foundation in particular track the decline in hope amongst young people between March 2020 and February 2021.

Given this change over time, and also an apparent increase in the gap between the wellbeing of older people (60+) and young people (18-29) in the Covid-19 Social Study since January 2021, one might expect that the pandemic may have originally affected the wellbeing of older people more, but that the evolution of the pandemic and lockdowns lead to greater impacts on young people in the long-term. However, we have not found a robust analysis of this evolution using representative samples such as the OPN or the APS.

Ethnicity

Two studies using the APS have found that the pandemic has affected the wellbeing of some ethnic minorities more than white people – an early study in May 2020 conducted by Simetrica-Jacobs and a more recent study conducted by the What Works Centre for Wellbeing using data up until September 2020. However the latter only found a consistently larger negative effect across the subjective wellbeing measures for Pakistanis.

Socio-economic status

The previously mentioned study conducted by Cambridge University in July 2020 highlighted that people in managerial or professional jobs suffered larger subjective wellbeing losses as a result of the pandemic than other groups. They speculate that this may be because higher status individuals may have perceived they had more to lose as a result of the pandemic. For example, restrictions on travel and consumption would have affected them more than people with lower incomes. There were also many who never worked from home and so were less affected by the transition to home working.

Forthcoming research by the What Works Centre for Wellbeing, using APS data up until September 2020 confirms this pattern, finding that the greatest wellbeing losses are for those with higher education levels. Meanwhile, the pattern for income is more mixed. The biggest negative effect of the pandemic on subjective wellbeing was for the top income quintile, but the effect on the second income quintile was smaller than for lower income groups. As such, there was no linear relationship between income and the effect of Covid.

Conversely, analysis of Understanding Society by the Resolution Foundation, has shown that whether you rent or own your home, is a more significant predictor of wellbeing during the pandemic than prior to the pandemic, with the gap between renters who have lower subjective wellbeing and homeowners who are relatively happier, increasing. This makes sense, given that housing conditions are often better for homeowners, and that most people have spent more time at home during the pandemic.

![]()