How has Covid-19 exposed housing inequalities?

Covid-19 has affected all aspects of our lives, including our wellbeing, which hasn’t yet returned to pre-pandemic levels, as data from the ONS shows.

For a full recovery, it is necessary to understand the full breadth of what drives our wellbeing, and how these drivers interact with each other – in order to inform our policies and be the basis for making everyday decisions on how to spend our time and money.

Our wellbeing inequalities project, Covid:WIRED, looks at emerging research on the impact of the pandemic. It holds a database of studies that identify what aspects of life have been affected by the pandemic, as well as which individuals have been most impacted by these changes.

Our report published today, in partnership with the Centre for Thriving Places and Shelter, uses the evidence obtained from the dashboard to look in depth at the wellbeing inequalities that Covid-19 has opened up within the housing system.

There are long-standing inequalities within the housing system both in the type and quality of housing and the affordability and access to amenities. These have a direct impact on the drivers of wellbeing, such as physical and mental health and our social relationships.

Since the start of lockdown in March 2020, people have spent more time at home, so their immediate surroundings had a greater impact on shaping their quality of life. We know that housing conditions had a stronger independent effect on wellbeing in the first lockdown than before the pandemic.

Before the pandemic

There were already long-standing inequalities in housing in the UK which affected the capacity of different groups to respond to lockdown and changing patterns of work and leisure. These include:

Housing quality

- A higher proportion of people in the private rented sector live in poor housing conditions.

- Young people are particularly likely to live in smaller homes and in worse conditions.

- One in five children in low-income households spend their time in an overcrowded home. This rate increases for BAME groups.

Overcrowding

- BME households are more likely than white British people to live in households with fewer rooms than occupants.

- The proportion of households with no garden is higher among ethnic minorities.

- Manual workers, casual workers and the unemployed are almost three times as likely as those in managerial, administrative, professional occupations to be without a garden.

Why were these inequalities relevant during the pandemic?

During the first lockdown, many households experienced multiple types of vulnerabilities simultaneously, particularly working-age households. For example:

- Physical health inequalities associated with housing have been exacerbated as poor housing and overcrowding have been linked to increased transmission of the virus.

- Younger people have been more likely to experience lockdown in homes with less space, more damp, fewer gardens and/or in derelict or congested neighbourhoods than older people.

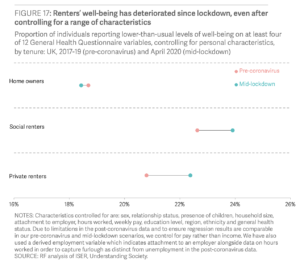

- Renters appear to have experienced lower wellbeing in the pandemic than owners, although all tenures are negatively affected by financial insecurity due to the pandemic.

Rising homelessness

Although there were increases in demand for services for homeless people, and a continuing flow of new rough sleepers throughout the pandemic, there was also increased access to emergency support.

New ways to support people facing multiple disadvantages were quickly implemented across the country, including emergency accomodation for homeless people and more autonomy and flexibility for workers. This brought short term benefits, for example facilitating self-isolation and providing clinical support for substance use issues, and a foundation for recovery.

Ligia Teixeira from the Centre for Homelessness Impact reflects on this:

“Homelessness certainly harms wellbeing and is one of the most tragic forms of poverty, blighting rich countries as much as poor ones. Homeless people experience poorer physical and mental health than the general population and are also at higher risk of death.

“The UK government has pledged to end rough sleeping in England by 2024 and has made progress towards this, but this is only one type of homelessness. The number of households living in temporary accommodation, for instance, has risen sharply and demand is set to continue to rise over coming months.

“This review is welcome because to end homelessness for good we need to focus on what works: to improve how we use research and data to establish an evidence base of interventions that are proven to have impact and to deliver value for money.”

Why do these findings matter for wellbeing?

The emerging evidence has shown the immediate and direct impacts of our housing on our ability to respond to the pandemic:

- The need for space to quarantine safely from others and spend long periods of time inside to rest, work and exercise was not met by all forms of accommodation.

- The effect was particularly acute for those on low incomes, from ethnic minorities and the young, including where those groups intersect.

- Housing conditions not only had a direct impact on wellbeing, but also on the drivers of wellbeing such as health and employment.

Hilary Burkitt, Head of Research at Shelter UK, talks about the findings from the review:

“Through the lockdowns that have punctuated the COVID-19 pandemic we have been urged to ‘stay home’. The increased time we have spent within our own four walls has underscored the importance of home.

“For the fortunate it has been a welcome reconnection and reminder of their value to our wellbeing. However, for too many of us it has highlighted the immense challenges we face when we don’t have stability, security and safety. The pandemic has exposed the inequality that lies at the heart of our housing system.”

Monitoring both the tangible effects of housing on the drivers of wellbeing, as well as its effects on subjective wellbeing, will help to craft and evaluate policy and practice responses.