Considering community wellbeing in times of Covid-19 and levelling up

The Different People, Same Place research project is led by the Universities of Birmingham, Durham and Warwick and supported by the Centre for Ageing Better and Spirit of 2012. It explores the interrelationships between individual and community wellbeing. Here, the researchers discuss what they found.

How can resources best be allocated to improve individual and community wellbeing in line with the levelling up agenda, especially missions eight and nine around wellbeing and pride in place? Our research project brought individual and community wellbeing researchers together to agree on principles about the relationships between wellbeing expressed at individual and community scales. We used theory and insights from existing work, conducted new analyses of survey data, and considered the viewpoints of those working in local government, the third sector, politics, and academia.

Many people are confused about what community wellbeing is, making it hard to develop initiatives to improve community wellbeing. We tried to clarify this.

There are two common ways of assessing community wellbeing. First, objective measures such as unemployment rates or hospital admissions provide community level indicators of wellbeing. Second, subjective individual assessments of life in the community, such as sense of belonging or whether they like the neighbourhood, can be averaged into community-level wellbeing scores. It is also possible to aggregate individual subjective wellbeing scores (anxiety, happiness) at the community level or ask people open-ended qualitative questions about how they perceive their communities.

Notably, it can be difficult to capture community wellbeing because people might belong to multiple communities that do not overlap and what individuals perceive as their communities can differ from those defined by researchers or policymakers. Participants in our studies thought there was a lack of easily available community-level data, including timely and representative local authority-level data on subjective wellbeing that can be easily disaggregated to discover inequalities within communities. It will be interesting to see how the measurement framework for the levelling up agenda develops.

Reflecting on our project, we have some recommendations and conclusions for future work on community wellbeing initiatives:

- Map it out. In designing and evaluating specific community-level initiatives and interventions, consider observations across a causal chain at both individual and community-levels to understand effectiveness, and consider what would have happened if the initiative hadn’t occurred. Our project created a visual model as a starting point to guide theories of change.

- Know the system. A full picture of wellbeing needs a more complex and potentially systems-based approach allowing for differential impacts across the wellbeing distribution, including that wellbeing spreads between individuals and communities.

- View the evidence. In selecting an initiative, look to reviews of many studies, considering their generalisability, headroom for improvement, fit with the community context and perspectives, the challenges and importance of co-production and funding.

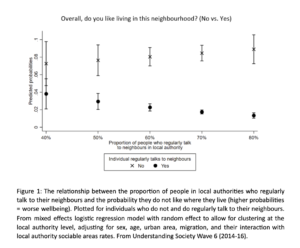

- Consider inequalities. A recent review screened over 2,000 studies of urban wellbeing initiatives but none of the included studies investigated the experiences of people with disabilities, migrants, or ethnic minorities. Not everyone experiences their community contexts in the same way: our findings from analysis of survey data showed that people who did not regularly talk to their neighbours fared worse in more sociable areas, perhaps because they felt left out (Fig 1).

Many of our research participants suggested co-production to address wellbeing inequalities, allowing under-represented groups to present ideas of how interventions might work better for them. However, there is limited evidence on whether and how co-production affects subjective wellbeing outcomes. Alongside rigorous effectiveness evaluations that consider rich dimensions of individual and community wellbeing across causal chains, and a focus on inequalities, future research should consider the wellbeing consequences of co-produced initiatives – in the context of levelling up and beyond.

Resources in this project

Download and read the technical report

Use the model to understand what links community and individual wellbeing