Last week was the launch of Measuring Good Work from RSA, Future Work Centre and Carnegie UK. Today, the Centre publishes Promotion and Job Security, an evidence review and briefing that looks at all the published evidence on how progression at work impacts wellbeing. Here, Deborah Hardoon, Head of Evidence, shares the key findings from the review carried out by the Work and Learning team, as well as potential implications for employers and policymakers.

Go to Resource page

There is already evidence that being in work is good for our wellbeing, and that being in a job that we see as high quality is even better.

This review published today – Progression and Job Security – tries to unpack an aspect of good quality employment often taken for granted as having a positive impact on wellbeing: progression at work. It draws on evidence from 17 different studies.

Before delving into the key findings, it’s important to note that progression can encompass lots of different elements. For example, this might mean:

- more responsibility,

- increased hourly pay,

- more hours of work,

- a more stable and secure job,

- or any combination of the above.

Conversely, we could also experience trade-offs – more responsibility might mean more stress too.

Because of the measures used in the reviews, we cannot say which of the specific elements of workplace progression improved wellbeing.

Key findings

“Being promoted can improve our #wellbeing in the short-term, but the effect fades over time – new evidence from @whatworksWB “

The graph below is from one study in the review, based on a sample of 2,681 employed individuals between 2002 and 2010. The greatest increase in job satisfaction was observed 0-6 months after promotion, but after this point job satisfaction began to decline, and was statistically insignificant two years after the promotion.

“Promotions associated with poorer #mentalhealth in the longer-term; with mixed findings on the immediate effects – new evidence from: WhatWorksWB”Promotions may be associated with poorer mental health in the longer-term; with mixed findings on the immediate effects

In another study from the review, people who took a larger promotion – from non-supervisory roles to managerial roles – reported that their physical and mental wellbeing had improved in the first year. However, by the third year, their mental strain had worsened, compared to those who hadn’t been promoted.

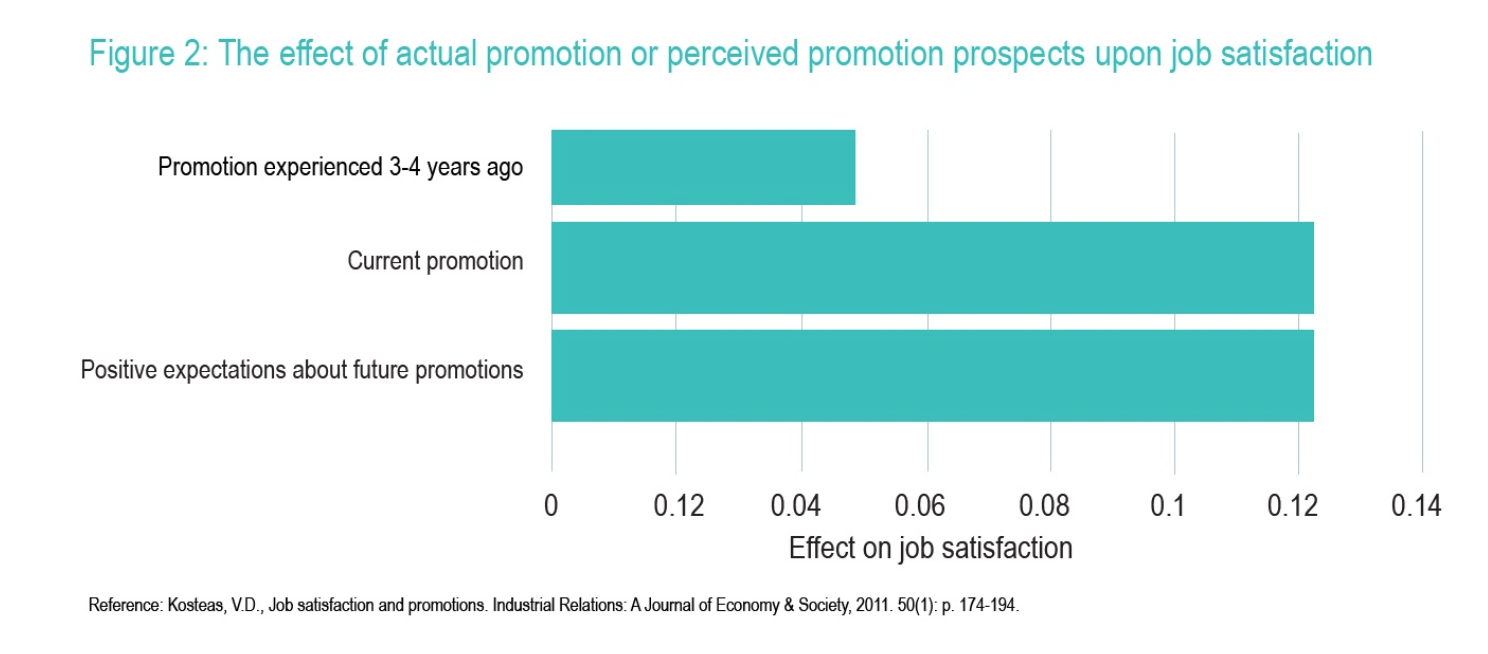

“Both actual promotions and positive expectations about future promotions had similar effects on self-reported job satisfaction- new evidence from @whatworksWB” Having a job with career prospects can make an important contribution to a person’s wellbeing

As the graph below – based on 30,000 individual-year observations from 1998-2006 – shows, both actual promotions and positive expectations about future promotions had comparable effects on self-reported job satisfaction.

Some forms of insecure or temporary employment are associated with poorer #wellbeing – new evidence from @WhatWorksWB Some forms of insecure or temporary employment are associated with poorer wellbeing

In four studies, insecure employment is associated poorer wellbeing for all individuals, and in two additional studies, insecure employment was worse for women.

Simply moving into permanent employment may not produce better #wellbeing outcomes when compared to temporary work. This depends on job quality overall. New evidence from @WhatWorksWB”Moving into permanent employment may not produce better wellbeing outcomes when compared to temporary work. Where there are improvements, these are mainly driven by greater satisfaction with job security

While the review does not speculate on the cause, it could be that an increase in job security from moving to a permanent job may not be enough to compensate for what else is lacking in a job. If other aspects of what makes for quality work are absent – things like autonomy, social connections and so on – then temporary work may offer more job satisfaction when job security is accounted for.

Implications for employers and policy makers

You can read the implications in full in the briefing, but these findings seem to suggest that employers could usefully consider how to create a work environment where progression opportunities to more challenging roles are supported and accessible to staff on both permanent and temporary contracts.

For policymakers, the evidence points to identifying opportunities to reduce the negative wellbeing effects of job insecurity across all job types. This could be achieved, for example, through creating support systems for people on fixed-term contracts to:

- transition between contracts;

- identify progression opportunities and career development support, including training.