A new model of individual and community wellbeing

Introduction

With the project Different People, Same Place, we explored the relationship between community wellbeing and individual wellbeing.

The work also looked at how this relationship differs for different locations and individuals, and sought to answer the research question: What are the relationships between community wellbeing and the wellbeing of different individuals and identified groups within that community?

As part of the project, the team mapped mechanisms that link community and individual wellbeing, and inequalities, together. The result is the Model of Individual and Community Wellbeing.

Model presentation

The team leading the research are Laura Kudrna, Oyinlola Oyebode, Sarah Atkinson and Sarah Stewart-Brown. In this video, Laura presents the model, who and what it’s for, and how it might help organisations with their work – bridging the research with practical use:

Perhaps this approach to individual and community wellbeing will be useful to you, especially if you are thinking about evaluating the effectiveness of community initiatives, and its impact on different but related levels of individual and community wellbeing.

Mechanisms - making the link(s)

While focusing on community wellbeing can help us understand the differences between places, understanding individual wellbeing can bring focus to the different experiences of people within the same place, helping us to better understand the drivers of inequality and disadvantage. Unpacking how individual wellbeing and community wellbeing may be related and how changes in one may lead to changes in the other was at the heart of this project.

The model shows some of the pathways through which different interventions and initiatives might impact individual and community wellbeing. It can be complex to change wellbeing and so the model does not seek to explain everything. Instead, the purpose of the model is to inform work in this area by providing more clarity about the relationships between individual and community wellbeing.

Individual wellbeing

Feeling good and functioning well. Affected by internal and external factors such as the physical and social context of the place where we live and personal relationships.

Community wellbeing

This is how we are doing as a community. It is about how a group of people are doing as a group and goes beyond just adding up the individual wellbeing of the people in that group, to include considerations of how wellbeing is distributed. In this study we defined community wellbeing by thinking about subjective and objective aspects of wellbeing that are of interest at the community level as opposed to at the individual, national or

international levels.

National wellbeing

How we’re doing as individuals, communities and as a nation, and how sustainable that

is for the future.

Model structure and usage

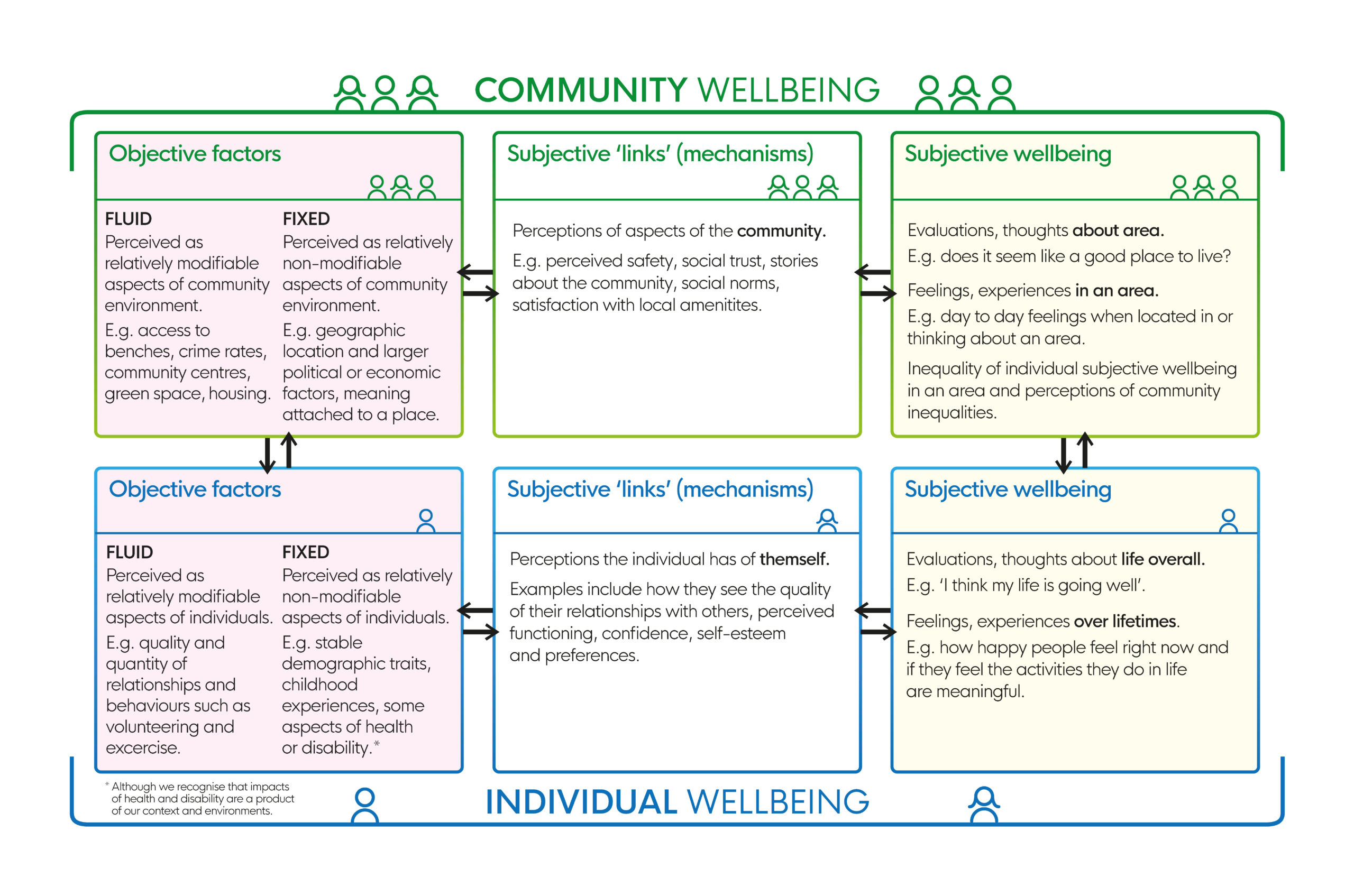

On the top there are three components of community wellbeing, which are community-level objective factors, subjective ‘links’ or mechanisms, and subjective wellbeing. Communities may be groups like local areas and communities (such as workplaces, schools, or communities of identity, such as religion and sexuality), although the text in this model is about local areas, and it could be modified to be about another community.

On the bottom there are the three components of individual wellbeing, which refer to people within these communities: individual level objective factors, subjective psychological ‘links’ or mechanisms, and subjective wellbeing.

The model could be arranged differently, in terms of what is on the left and what is on the right, because there are bidirectional relationships between these concepts, represented by bidirectional arrows. More arrows could be added too, depending on the relationships proposed for a particular context.

Currently, the model is arranged from the perspective of decision-makers who have access to levers that allow them to alter the objective community factors shown on the upper left. Sometimes objective community factors are perceived as more fluid and easier to change, such as the provision of benches in the local area or housing availability. Sometimes they are seen as more fixed and relatively harder to change, such as whether a community is in an urban or rural location and wider political factors.

On the right are subjective reports of wellbeing. For individuals, these could be thoughts about life overall or their day-to-day feelings. At the community level, these could be thoughts about the community, feelings when in the community, or inequalities in subjective wellbeing. In the middle, linking the objective factors to wellbeing experiences, are subjective ‘links’ or mechanisms. These are the processes by which changes on the left-hand side might convert into wellbeing on the right hand side. Mechanisms might be at the individual level, such as if an individual has high self-esteem, or at the community level, such as individual perceptions that local facilities like shops and parks are satisfactory, or the proportion of people in an area that perceive the area positively.

The difference between the subjective mechanisms and subjective wellbeing is that the mechanisms are about how people think and feel about certain aspects of their lives or their communities (e.g. their sense of belonging to the local area, their relationships with others or how easily they can access local services) whereas subjective wellbeing is more purely about thoughts and feelings irrespective of these specific aspects (an evaluation of whether it’s a good place to live, day-to-day feelings about the place, an evaluation of how their life is going, how happy they feel right now).

As an example of a pathway cutting through some of the model, local-level income inequality (a fluid community objective factor) could be associated with someone feeling sad (individual subjective wellbeing) because people feel like they don’t belong to their local area (a subjective community mechanism). However, subjective wellbeing can drive community or individual objective factors – happier people might be more likely to volunteer, for example (Hansen, Aartsen, Slagsvold and Deindl, 2018). And the individual and community boxes are related: communities experiencing positive feelings about their area (top right) are likely to have individuals within them who are happier (bottom right), as has been shown for workplace communities (Whitman, Van Rooy and Viswesvaran, 2010).

In addition, the same fluid community intervention on the left, such as a park, may affect people with different fixed individual factors differently, such as people with mobility impairments who may be unable to use the park if it is not designed to be accessible.

Suggested citation for the report:

Kudrna L, Oyebode O, Quinn L, Atkinson S, Stewart-Brown S. The model of individual and community wellbeing, Model, March 2022, What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

Also in this project

References

Hansen, T., Aartsen. M., Slagsvold, B., and Deindl, C. (2018) Dynamics of volunteering and life satisfaction in midlife and old age: Findings from 12 European Countries, Social Sciences, 7 (5), pp doi:10.3390/socsci7050078 from https://whatworkswellbeing.org/wp-content/uploads/1920/10/volunteer-wellbeing-Oct-20_briefing.pdf

Whitman, D. S., Van Rooy, D. L. and Viswesvaran, C. (2010) ‘Satisfaction, citizenship behaviors, and performance in work units: A meta-analysis of collective construct relations’, Personnel Psychology, 63(1), pp. 41–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2009.01162.x.

References to pre-existing models shown in presentation

Araujo, N. (2021). The Community Spirit Level: A framework for measuring, improving and sustaining community spirit. Royal Society for Public Health, Health Foundation, Locality. Available at: https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/programmes/community-spirit-programme.html

Dahlgren, G. & Whitehead, M (1991). Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Background Document to WHO – Strategy paper for Europe. Institute for Futures Studies. ISSN: 1652-120X. Available at: http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10234/187797/GoeranD_Policies_and_strategies_to_promote_social_equity_in_health.pdf?sequence=1

Department for Education (2019) Understanding child and adolescent wellbeing: a system map. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/understanding-child-and-adolescent-wellbeing-a-system-map (Accessed: 7 March 2022).

Dolan, P., Laffan, K. and Kudrna, L. (2021) ‘The Welleye’, Frontiers in Psychology – Health Psychology. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.716572.

Pennington, A. et al. (2021). The Wellbeing Inequality Assessment Toolkit 2021. Project Report. University of Liverpool, Liverpool. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17638/03116863

South, J. Abdallah, S., Bagnall, A-M, et al. (2016), ‘Building community wellbeing – an initial theory of change’, Liverpool: University of Liverpool. https://whatworkswellbeing.files.wordpress.com/2017/05/theory-of-change-community-wellbeing-may-2017-what-works-centre-wellbeing.pdf

Downloads

- Download the Model of Individual and Community Wellbeing

- Watch the Model of Individual and Community Wellbeing presentation

- Download the presentation slides

You may also wish to read the blog article on this document.

Downloads

- Download the Model of Individual and Community Wellbeing

- Watch the Model of Individual and Community Wellbeing presentation

- Download the presentation slides

You may also wish to read the blog article on this document.

![]()

[gravityform id=1 title=true description=true ajax=true tabindex=49]